In

Copyright

Since

September 11, 2000

Help

for Kaiser

Permanente Patients on this public service web site.

Permission is

granted to mirror if credit to the source is given and the

material is

not offered for sale.

The Kaiser Papers is not by Kaiser but is ABOUT

Kaiser

PRIVACY

POLICY

ABOUT

US|

CONTACT

| WHY

THE KAISERPAPERS

| MCRC

|

Why

the

thistle is used as a logo on these web pages. |

In

Copyright

Since

September 11, 2000

Help

for Kaiser

Permanente Patients on this public service web site.

Permission is

granted to mirror if credit to the source is given and the

material is

not offered for sale.

The Kaiser Papers is not by Kaiser but is ABOUT

Kaiser

PRIVACY

POLICY

ABOUT

US|

CONTACT

| WHY

THE KAISERPAPERS

| MCRC

|

Why

the

thistle is used as a logo on these web pages. |

Kaiser Diagnostic and Treatment Documents

Kaiser Permanente Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Stroke Quartet III Inpatient Management Admission Criteria for Acute Ischemic Stroke/Acute Stoke/Anticoagulation in Acute Ischemic Stroke (Spelling errors from the original text have not been corrected) This page consists of three booklets printed as one.

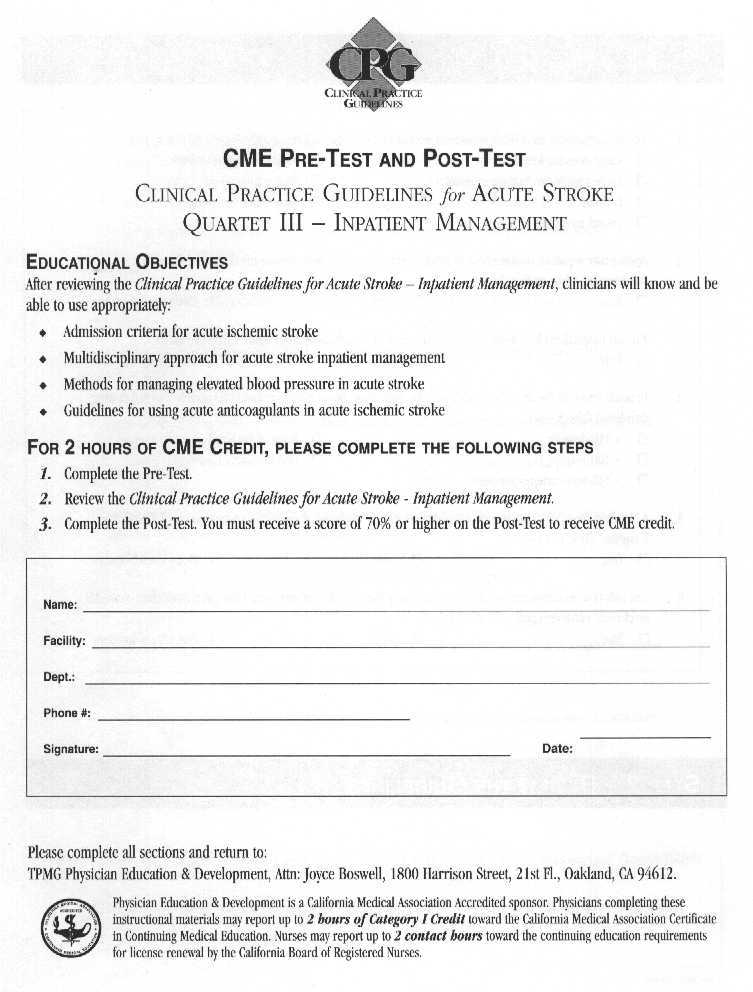

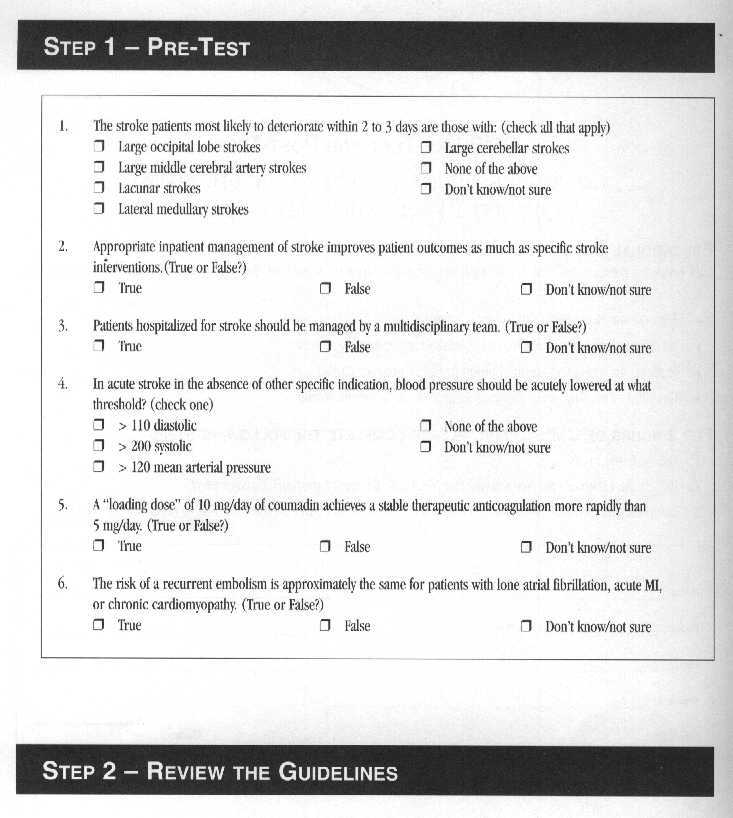

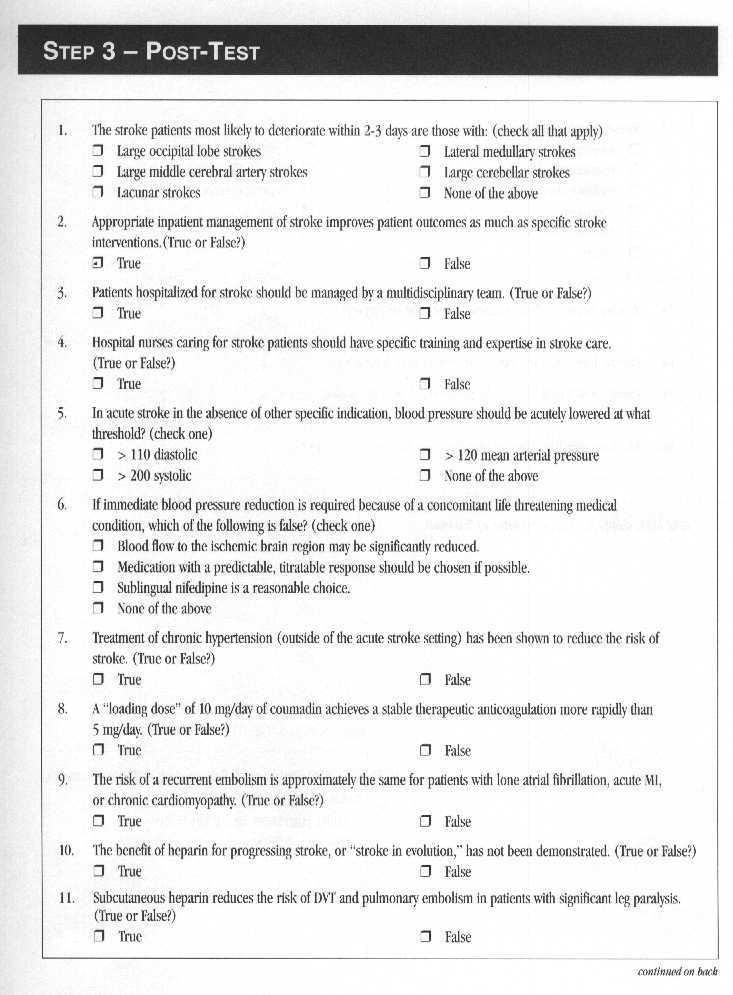

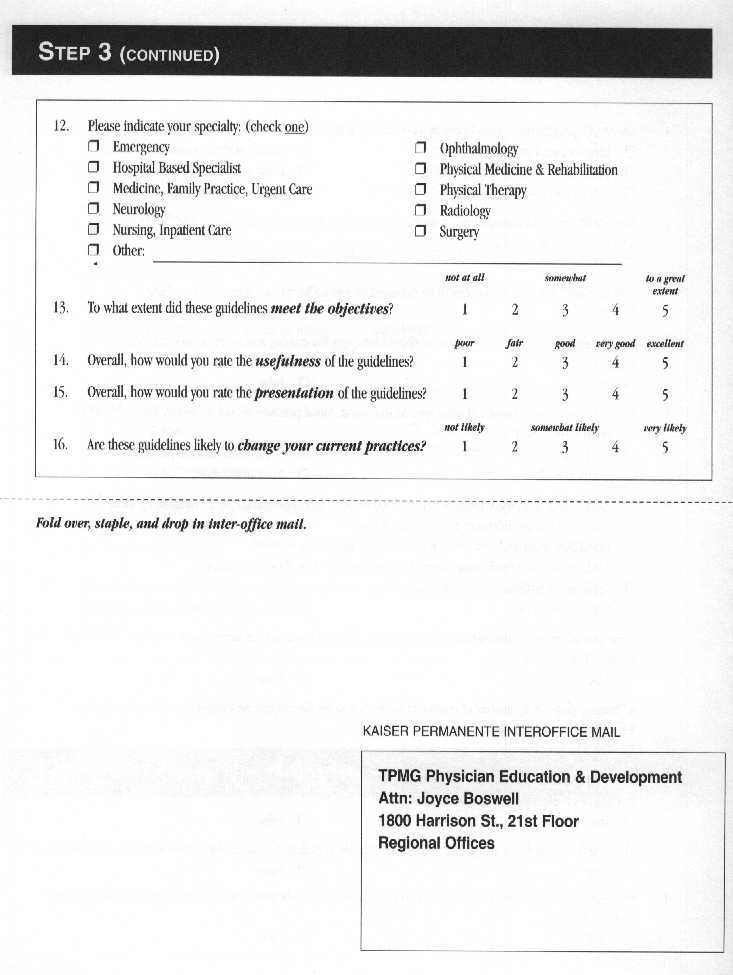

Also Included is CME-Pre-Test and

Post-Test  Clinical

Practice Guidelines for Acute Stroke Quartet III

Inpatient

Management Admission Criteria for Acute Ischemic Stroke

Clinical

Practice Guidelines for Acute Stroke Quartet III

Inpatient

Management Admission Criteria for Acute Ischemic Stroke

Inpatient Management of Acute Stroke

Management of Blood Pressure in Acute Stroke

Anticoagulation in Acute Ischemic Stroke endorsed by Chiefs of Neurology, Chiefs of Medicine, Chiefs of Emergency Medicine - April 1998

The Permanente Medical Group Clinical Practice Guidelines have been developed to assist clinicians by providing an analytical framework for the evaluation and treatment of selected common problems encountered in patients.

These guidelines are not intended to establish a protocol for all patients with a particular condition.

While the guidelines provide one approach to evaluating a problem, clinical conditions may vary significantly from individual to individual. Therefore, the clinician must exercise independent judgment and make decisions based upon the situation presented. While great care has been taken to assure the accuracy of the information presented, the reader is advised that TPMG cannot be responsible for continuedcurrency of the information, for any errors or omissions in this guidelines, or for any consequenses arising from its use.

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR ACUTE STROKE QUARTET III - INPATIENT MANAGEMENT CLINICAL LEADER Jerry Schlegel, MD; Neurology, San RafaelWORK GROUP Jai Cho, MD; Neurology, Santa Teresa John David, MD; Emergency Medicine, San Rafael Philip Eulie, MD; Medicine, San Francisco Ron Gaines, MD; Physical Medicine, San Rafael Dale Grahn, MD; Medicine, Park Shadelands Jeff Klingman, MD; Neurology, Park Shadelands Steven Okuhn, MD; Vascular Surgery, San Francisco Howard Slyter, MD; Neurology, Sacramento Bettiane Wiessler, RN; ICU Nursing, San Rafael LarryYeager, MD; Radiology, Redwood City Howard Barkan,MA,DrPH Stephen Sidney, MD, MPH; Division of Research Philip Bellman, MPH; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization

TOPIC LEADERS Admission Criteria for Acute Ischemic Stroke Howard Slyter, MD; Neurology, Sacramento Inpatient Management of Acute Stroke Dale Grahn, MD; Medicine, Park Shadelands Management of Blood Pressure in Acute Stroke Jeff Klingman, MD; Neurology, Park Shadelands Anticoagulation in Acute Ischemic Stroke Howard Slyter, MD; Neurology, Sacramento

CLINICAL REVIEW GROUP The following individuals reviewed these guidelines and contributed to its final content. Neurology Scott Abramson, MD, Hayward; Garrick Amgott-Kwan, MD, Oakland; Everett Austin, MD, San Francisco; Allan L. Bernstein, MD, Santa Rosa; Raj Bhandari, MD, Santa Teresa; Robert Elmore, MD, Santa Clara; Robin Fross, MD, Hayward; Barbara Gardner, MD, Sacramento; Michael Gibbs, MD, Roseville; Browne Goode, MD, San Francisco; James Laster, MD, Santa Clara; Garter Mosher, MD, Sacramento; George Palma, MD, Roseville; Joel Richmon, MD, Oakland; Sidney Rosenberg, MD, South San Francisco; Antoine Samman, MD, Vallejo; R. Jay Whaley, MD, Redwood City Medicine Tadios Amare, MD, Vacaville; Henry Brodkin, MD, Redwood City; Paul Feigenbaum, MD, San Francisco; Pansy Kwong, MD, Oakland; David Langkammer, MD, Antioch; James Martin, MD, San Rafael;Joan Pont, MD, San Rafael; Michael Weaver, MD, Martinez; David B Williams, MD, Vallejo Emergency Medicine George Bulloch, MD, Redwood City; Uli Chettipally, MD, South San Francisco; Gary Hashimoto, MD, Walnut Creek; Pankaj Patel, MD, Sacramento; Christina Shih, MD, San Francisco Hospital Based Specialists Mark Clark, MD, HBS, Vallejo; Lewis Lehman, MD, HBS, San Francisco Pharmacy Cathlene Richmond, PharmD, Regional Pharmacy Operations PROJECT MANAGEMENT Philip Bellman, MPH; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization DESIGN AND PRODUCTION Wendy Jung, MA, TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Linda Rogers, MPA; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization

Copyright 1998 The Permanente Medical Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Please contact TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization at 510-987-2309 or tie-line 8-427-2309 for permission to reprint any portion of this publication. For additional copies of the guidelines, please call 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950.

CLINICAL PRACTICE GLIIDELINES

Summary of Guidelines Classification and Grading of Recommendations

ADMISSION CRITERIA FOR ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE Purpose Background Recommendations References

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE Purpose Background Recommendations References Appendices

MANAGEMENT OF BLOOD PRESSURE IN ACUTE STROKE Purpose Background Recommendations References

ANTICOAGULATION IN ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE Purpose Background Recommendations References

Previously Published Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Stroke QUARTET I - ACUTE EVALUATION and TREATMENT (NOVEMBER 1996) *INITIAL BRAIN IMAGING for TIA and STROKE *TISSUE PLASMINOGEN AcnVATOR/or ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE *ACUTE EVALUATION and MANAGEMENT of INTRACEREBRAL HEMORRHAGE *INITIAL EVALUATION of SUSPECTED SUBARACHNOID HEMORRHAGE QUARTET II - TIA and MINOR ISCHEMIC STROKE (OCTOBER 1997) *INITIAL EVALUATION and TREATMENT of TIA and MINOR ISCHEMIC STROKE *HOSPITAL ADMISSION CRITERIA/orTRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK *INITIAL VASCULAR IMAGING for SUSPECTED CAROTID ARTERY STENOSIS *CAROTID ENDARTERECTOMY for SYMPTOMATIC CAROTID STENOSIS

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE for ACUTE STROKE QUARTET III - INPATIENT MANAGEMENT - SUMMARY OF GUIDELINES

ADMISSION CRITERIA FOR ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE Not all patients with ischemic stroke will necessarily benefit from hospitalization. Hospitalization is indicated when the clinical deficit is substantial and/or anticipated to progress, or when complications have occurred or are anticipated. Patients suitable for specific interventions, such as thrombolytic treatment, acute anticoagulation, or urgent vascular surgery, should also be hospitalized, as should patients in whom acute evaluation may lead to these or other interventions.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE Hospitalized patients should be managed with specific goals in mind: evaluation and treatment, prevention of complications, initiation of early rehabilitation, and initiation of education and secondary prevention. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended that begins in the Emergency Department (ED) and includes the ED physician, an on-call stroke consultant, the attending physician, nursing personnel with stroke expertise, Physical Therapy, and Discharge Planning. A stroke pathway or carepath to coordinate the multidisciplinary care is recommended. A designated Stroke Unit facilitates this multidisciplinary approach and is recommended where feasible.

MANAGEMENT OF BLOOD PRESSURE IN ACUTE STROKE Acute treatment of elevated blood pressure in acute ischemic stroke is not generally recom- mended, as this intervention may aggravate an ischemic stroke syndrome and worsen the clinical outcome. However, extreme elevations of blood pressure, malignant hypertension, aortic dissection, or myocardial infarction may warrant specific intervention to reduce blood pressure. The continuation of previously prescribed drugs with antihypertensive effects should be based on a consideration of the original indication of the medication, the current blood pressure, and the stability of the stroke deficit.

ANTICOAGULATION IN ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE Acute anticoagulation with heparin is generally not recommended in patients with completed thrombotic stroke. Progressing stroke is a situation in which acute anticoagulation with heparin may be reasonable. Acute anticoagulation with heparin is also reasonable in cardioembolic stroke resulting from a source with high-risk of early re-embolization (cardiomyopathy, rheumatic or prosthetic valvular disease, and acute myocardial infarction) if hypertension is controlled, CT excludes hemorrhage, and the infarct is not large. Stroke resulting from non-valvular atrial fibrillation generally should not be treated acutely with heparin as the risk of early re-embolization is relatively low; initiation of warfarin (starting dose of 5 mg/day) without preceding heparin is recommended.

CLASSIFICATION AND GRADING OF RECOMMENDATIONS

Each guideline recommendation is justified in terms of the level of research evidence supporting it and the degree of consensus on it among the members of the work group. The distinction between support derived from scientific studies and that derived from expert opinion is important. Well-performed and relevant scientific studies provide a higher standard of evidence when they are available, but many aspects of medical care have not been addressed by such studies. Expert judgments supplement research evidence by factoring in clinical experience and human values that are not easily captured in scientific studies, and by extrapolating from scientific findings that were obtained with specific populations under specific conditions to a broad clinical context. Support for recommendations is characterized as follows:

RESEARCH EVIDENCE Grade A Supported by the results of two or more randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that have good internal validity, and also specifically address the question of interest in a group of patients comparable to the one to which the recommendation applies (external validity). Grade B Supported by a single RCT meeting the criteria given above for "Grade A''-level evidence, by RCTS that only indirectly address the question of interest, or by two or more non-randomized clinical trials (case control or cohort studies) in which the experimental and control groups are demon- strably similar or multivariate analyses have effectively controlled for group differences. Grade C Supported by a single non-RCT meeting the criteria given above for "Grade B''-level evidence, by studies using historical controls, or by studies using quasi-experimental designs such as pre- and post-treatment comparisons.

EXPERT OPINION: Strong Consensus Agreement among at least 90% of the guideline work group members and expert reviewers. Consensus Agreement among at least 75% of the guideline work group members and expert reviewers.

Classifications adapted from U.S. Dept. of Public Health, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research.

ADMISSION CRITERIA for ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE

PURPOSE The purpose of this guideline is to identify patients with acute ischemic stroke for whom acute admission is appropriate and to review the primary diagnostic and therapeutic considerations bearing on this decision.

BACKGROUND Every year approximately 400,000 Americans suffer an acute ischemic stroke. Current published guidelines recommend that most, if not all, patients with acute ischemic stroke be admitted to a hospital, preferably to a "facility that specializes in the care of stroke," or a "stroke unit." 1,2 However, the rationale for admitting all strokes has not been clearly established, nor is there yet persuasive evidence that such a policy improves outcomes.

While there is no prospective controlled trial of admission vs. non-admission, an observational series of 976 patients with an acute stroke cared for by general practitioners in England found that 26% were never admitted. There were no differences in the functional, social, or emotional outcomes of patients managed at home vs. those admitted to hospital when the severity of the initial disability had been taken into account.3

A retrospective study from Harbor-UCLA Medical Center evaluated 168 stroke admissions from the emergency department (ED) for medical appropriateness using five criteria: another diagnosis that warranted admission; an inadequate home situation; altered mental status; an adverse event during hospitalization, including worsening of the deficit; and the need for a hospital-based treatment that could not be provided on an outpatient basis4 Only 39% of the admissions met these criteria. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that admission of all stroke patients was justified because subsequent deterioration could not be predicted in the ED.

Traditionally, patients have been admitted in order to initiate and complete their diagnostic evaluation, to administer therapies aimed at the prevention of progression or recurrence, and to prevent or treat complications. However, the technological revolution which allows outpatient scanning and vascular imaging for many cases, as well as the increased capability of skilled nursing facilities and home health resources to monitor patients, administer intravenous medications and provide acute rehabilitation, all challenge the rationale for routine admission of every stroke patient. At the same time, there are now treatments for acute stroke which may require hospitalization for drug administration and patient monitoring. The following sections discuss each of the rationales for admission.

Rationale for Admission: Acute Therapy Thrombolysis with t-PA has been shown to be effective in improving stroke outcome in carefully selected patients when given within three hours of stroke onset.5 Currently, the administration of this drug and the monitoring of such patients requires hospitalization.

The accumulation and spread of neurotoxic substances such as calcium and glutamate is believed to be the proximate cause of neuronal death in acute stroke. A variety of drugs intended for neuroprotection are under investigation. Some of these may require hospitalization for administration and/or monitoring.

The routine administration of heparin has been common-place in some institutions for patients with acute stroke who are neurologically stable. At present there is no evidence to support this practice. Two controlled studies, using either intravenous heparin or "medium dose" subcutaneous heparin (12,500 U ql2h) have shown no benefit.6,7

Rationale for Admission: Stroke Progression Every published series indicates that substantial numbers of patients with acute ischernic stroke deteriorate due to stroke progression in the several days after onset. Combining the data from several large series8,15 the risk of such deterioration is in the neighborhood of 30%. Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify reliably patients whose stroke will progress.

There have been several uncontrolled series reported on the use-of intravenous heparin in patients with progressing stroke. In these studies, the deficit has continued to progress in 21 to 50% of patients despite anticoagulation.16,19 Since these studies have lacked control groups, it is not possible to judge whether heparin-treated patients have done any better than they would have without treatment.

The Stroke Council of The American Heart Association found that "because data about the safety and efficacy of heparin in patients with acute ischemic stroke are insufficient and conflicting, no recommendation can be offered... Until more data are available, the use of heparin remains a matter of preference of the treating physician." 1

Even if heparin is of uncertain value in treating stroke progression, it is important to keep in mind that there are many causes of neurologic deterioration besides clot propagation and embolization that need consideration and may require intervention. Chief among these is hypotension, whether caused by the injudicious use of antihypertensive agents or by dehydration. Other important causes of deterioration include impaired cardiac output, hypoxia, seizures, intercurrent infection, sedative drugs or the development of cerebral edema. 20

Rationale for Admission: Acute Secondary Prevention in Patients with Embolic Stroke Patients who have suffered an embolic stroke may be at significant risk of a recurrent embolic event in the acute period. Many series of patients with cardiac emboli have been published, with early recurrence rates varying anywhere from 2% to 20%.21 Recommendations in this setting have varied widely: some have advised immediate heparin for all alert patients (once the CT has ruled out hemorrhage);22others have counseled delay for at least 48 hours23,24 still others would not advise heparin at all.25,26 Recently published data from the International Stroke Trial suggest that in patients with acute stroke and atrial fibrillation, heparin can accomplish a small reduction in stroke recurrence only at the cost of as many or more hemorrhagic complications.7 Again, in 1994 the American Heart Association felt that insufficient data prevented any firm recommendation for acute heparinization in this setting.1

Rationale for Admission: Acute Vascular Interventions There are patients with acute minor or fluctuating deficits in whom urgent carotid imaging and surgery might be considered. While such an approach is reported from some centers,27,28 the benefit of such aggressive therapy has not been systematically studied.1

Rationale for Admission: Acute Supportive Care There are patients who require acute supportive care for their new deficits or for acute complications of infarction, such as seizures, aspiration, or malignant arrhythmias. Patients especially at risk of neurologic deterioration from mass effect are those with large middle cerebral artery infarcts or large cerebellar infarcts. Close neurologic monitoring, intensive medical support, or the anticipation of possible neurosurgical intervention may all necessitate hospitalization.

Rationale for Admission: Additional Considerations There are many patients who do not meet any of the criteria above who still may warrant admission to an acute hospital, an observation unit, or a closely-monitored skilled nursing facility. Admission may be required by co-morbid medical conditions, unstable vital signs, a need to further clarify the mechanism of the stroke, the prevention or treatment of stroke complications, or the initiation of a stroke treatment plan, including secondary prevention and rehabilitation.

RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Admission is required for patients receiving t-PA or other acute therapies requiring in-patient administration and/or monitoring. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 2. Admission is required if urgent vascular surgery is indicated. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 3- Admission is recommended for patients with infarcts where clinical deficit is substantial and/or deterioration is anticipated. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 4. Admission is recommended when needed to treat acute complications of stroke, such as seizures, aspiration pneumonia, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), or arrhythmia. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 5. For other patients, admission may be indicated based on an evaluation of specific diagnostic or therapeutic needs of the patient and the availability of appropriate monitoring, care and follow-up in a non-hospital setting. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 6. Patients not admitted require an appropriate and timely diagnostic evaluation, the initiation of necessary therapy, and the initiation of an appropriate secondary prevention plan. Discussion with a stroke consultant (usually a neurologist) and appropriate follow-up with neurology and/or primary care is generally recommended. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

REFERENCES 1. Adams HP Jr, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1994; 9: 1901 -14. 2. Lanska DJ. Review criteria for hospital utilization for patients with cerebrovascular disease. Task Force on Hospital Utilization for Stroke of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 1994; 44:1531-2. 3. Wade DT, Langton Hewer R. Hospital admission for acute stroke: who, for how long, and to what effect? J Epidmiol Community Health 1985; 39:347 -52. 4. Henneman PL, Lewis RJ. Is admission medically justified for all patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack? Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:458-63. 5. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. NEnglJMed 1995; 333: 1581 - 7. 6. Duke RJ, et al. Intravenous heparin for the prevention of stroke progression in acute partial stable stroke. Ann Mem Med 1986;105:825-8. 7. The International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. The International Stroke Trial (1ST): a randomized trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Lancet 1997;349: 1569 - 81. 8. Jones HJ, Millikan CH. Temporal profile (clinical course) of acute carotid system cerebral infarctlon. Stroke 1976; 7:64-71. 9. Jones HR Jr, et al. Temporal profile (clinical course) of acute vertebrobasilar system cerebral infarction. Stroke 1980; 11:73-7. 10. Patrick BK, et al. Temporal profile of vertebrobasilar territory infarction. Prognostic implications. Stroke 1980; 11: 643 - 8. 11. Irino T, et al. Angiographical analysis of acute cerebral infarction followed by "cascade''-like deterioration of minor neurological deficits. What is progressing stroke? Stroke 1983; 14:363-8. 12. Britton M, Roden A. Progression of stroke after arrival at hospital. Stroke 1985; 16:629 -32. 13. Davalos A, et al. Deteriorating ischemic stroke: risk factors and prognosis. Neurology 1990; 40: 1865 - 9. 14. Wityk RJ, et al. Serial assessment of acute stroke using the NIH Stroke Scale. Stroke 1994; 25:362 - 5. 15. Toni D, et al. Progressing neurological deficit secondary to acute ischemic stroke. A study on predictability, pathogenesis, and prognosis. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:670 - 5. 16. Dobkin BH. Heparin for lacunar stroke in progression. Stroke 1983; 14:421-3. 17. Haley EC Jr, et al. Failure of heparin to prevent progression in progressing ischemic infarction. Stroke 1988; 19: 10 -14. 18. Slivka A, Levy D. Natural history of progressive ischemic stroke in a population treated with heparin. Stroke 1990; 21: 1657 - 62. 19. Dahl T, et al. Heparin treatment in 52 patients with progressive ischemic stroke. CerebrovascDis 1994; 4: 101 - 5. 20. Caplan LR. Treatment of "progressive" stroke. Stroke 1991; 22: 694-5. 21. Safety of heparin in acute ischemic stroke [letters]. Neurology 1996;46:589-91. 22. Chamorro A, et al. Early anticoagulation after large cerebral embolic infarction: a safety study. Neurology 1995; 45: 861 - 5. 23. Cerebral Embolism Task Force. Cardiogenic brain embolism.The second report of the Cerebral Embolism Task Force. Arch Neurol 1989; 46:727 - 43. 24. Hart RG. Cardiogenic embolism to the brain. Lancet 1992;339:589-94. 25. Scheinberg P. Heparin anticoagulation [editorial]. Stroke 1989;20:173-4. 26. Phillips SJ. An alternative view of heparin anti- coagulation in acute focal brain ischemia. Stroke 1989; 20:295 - 8. 27. Walters BB, et al. Emergency carotid endarterectomy. / Neurosurg 1987:66:817-23. 28. Meyer FB, et al. Emergency carotid endarterectomy for patients with acute carotid occlusion and profound neurological deficit. Ann Surg 1986; 203:82 - 9.

INPATIENT MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE STROKE

PURPOSE The purpose of this guideline is to provide a framework for the inpatient management of acute stroke. BACKGROUND Recent years have witnessed many developments in the overall management of patients with cerebrovascular disease. Risk factor modification has improved stroke prevention. Medical and surgical interventions after transient ischemic attack (TIA) and minor ischemic stroke reduce incidence of major stroke in selected patients. Acute medical and surgical treatment is beneficial for identifiable subsets of stroke patients. In addition, prevention of acute complications, along with early rehabilitation, improve clinical outcome after stroke.1-3

The acute management of patients with TIA and stroke has traditionally been in the setting of an acute care hospital, The benefit of routine hospitalization for all of these patients, however, is in question.4-6 After initial evaluation in the emergency department (ED), a patient with TIA or stroke may be hospitalized for further evaluation and treatment, transferred to a skilled nursing facility (SNF) for nursing care, or managed as an outpatient. Which of these settings is appropriate depends on the need for clinical observation, the specific medical or surgical treatment considered, and the intensity of nursing care anticipated. The patient's stroke syndrome, the severity of neurologic deficit, and the medical condition and social circumstances of the patient, all help determine the appropriate acute management setting.

An acute care hospital is the most intense management setting, and care should be directed toward accomplishing specific goals which improve clinical outcome. For patients admitted to a SNF for acute management, the intensity of medical treatment and nursing care will be less, but the goals of management should be the same. The general principles of inpatient management for acute stroke outlined here should apply as well to the management of patients with stroke in a SNF, and to the outpatient management of patients with acute cerebrovascular disease.

GOALS OF ACUTE MANAGEMENT OF PATIENTS WITH STROKE There are four goals in the acute management of patients with stroke. These are: Evaluation and treatment Prevention of acute complications Initiation of early rehabilitation Initiation of education and secondary prevention

Evaluation and Treatment The goal of the initial evaluation of a patient with acute stroke is to characterize the stroke syndrome sufficiently to initiate appropriate treatment. This usually occurs in the ED. Clinical assessment and CT brain imaging are generally required to identify the stroke syndrome as either an ischemic stroke, an intracerebral hemorrhage, a subarachnoid hemorrhage, or a cerebral venous thrombosis. The cerebrovascular anatomy of the stroke syndrome, and the severity of the neurologic deficit, should also be assessed during the initial evaluation. Accurate initial evaluation is pivotal in directing appropriate initial management, and often requires discussion or consultation with a stroke consultant.

Further evaluation and treatment may require repeated assessment of neurologic status. With or without treatment, the severity of neurologic deficit may progress, fluctuate, or improve. Additional brain imaging, as well as vascular or cardiac imaging, may be necessary to establish the stroke mechanism and specific stroke pathophysiology. These determinations may direct appropriate specific treatment. Inpatient management of acute stroke thus involves evalua- tion and treatment that proceed simultaneously.

Prevention of Acute Complications

Prevention of stroke complications improves clinical outcome to a degree similar to that accomplished with specific stroke treatment.7 The major complications to be anticipated and prevented are: adverse effects of medications; aspiration pneumonia; dehydration and malnutrition; skin breakdown; urinary tract infection; deep venous thrombosis (DVT); and falls.

Medical treatment should avoid unnecessary use of drugs which depress central nervous system function. The use of such drugs in patients with acute stroke has been associated with worsened clinical outcome.8 Similarly, the use of anti-hypertensives in acute stroke should generally be avoided, as lowered blood pressure in this setting may aggravate the stroke syndrome.

The routine assessment of aspiration risk and the use of a routine swallow evaluation reduce the incidence of aspiration pneumonia complicating stroke.9-11 Stroke patients are at risk of acute dehydration and malnutrition. Swallow evaluation aids in establishing need for parenteral fluids, nasogastric feeding tube, or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy." Early enteral intake is desirable to facilitate discontinuation of otherwise unnecessary intravenous catheters.

Attention to skin integrity and the prevention of pressure ulcers is important. Avoidance or rapid discontinuation of urinary catheters reduces the incidence of urinary tract infections. DVT and pulmonary emboli are preventable complications of stroke, and their occurrence is reduced by mobilization, pressure stockings, and/or low dose anticoagulation.13,14

Early mobilization reduces the risk of many of the acute complications of stroke, and improves clinical outcome.13,15 With ambulation, however, the risk of falling increases. Thus progressive mobilization needs to proceed along with assessment of falling risk and preventative measures.

Prevention of acute complications of stroke requires an expertly trained nursing staff working with an attending physician familiar with inpatient stroke management. Physical therapy, nutritional services, and pharmacy are also involved. Speech therapy and occupational therapy may be involved when necessary. A predetermined inpatient plan, such as a stroke carepath, coordinates inpatient management and reduces the incidence of acute complications.16,17 The acute care of patients in a geographically designated nursing stroke unit has also been associated with a lower incidence of acute complications.18

Initiation of Early Rehabilitation The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Post-Stroke Rehabilitation Clinical Practice Guidelines emphasize that rehabilitation should begin in the acute care setting.3 Initiation of early rehabilitation aids in preventing acute complications and improves long-term functional outcome. Early mobilization and the initiation of rehabilitation in the inpatient setting will require input from physical therapy.

Determining the appropriate rehabilitation plan and setting requires early assessment. The transition from the acute inpatient setting to the rehabilitation setting needs to be accomplished smoothly so that all relevant clinical information is reliably transferred to the physician accepting the patient, and so that continuity of ongoing care is assured. Initiation of early rehabilitation will rely on the discharge planner to coordinate the transition from the acute inpatient setting to the appropriate rehabilitation setting.

Initiation of Education and Secondary Prevention The management of patients with acute stroke and TIA includes addressing education and secondary prevention. Identification of the stroke mechanism and specific patho-physiology provides the basis for subsequent interventions. In part these interventions will involve patient education and life style modification. This aspect of patient education will be the beginning of a life long process.

Stroke also affects the patient's entire family. Educational efforts during acute management therefore should address family needs. The family's understanding of the course and prognosis allows the development of realistic expectations. Education of the family members may need to focus on prevention of complications as well as on rehabilitation. Alternatively, end-of-life issues may need to be addressed, and psychological support of the family is often necessary.

Advance Directives may require family members to make critical decisions. If Advance Directives have not been completed, family education and involvement is even more crucial.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH TO ACUTE MANAGEMENT

The acute management of patients with stroke has evolved into a multidisciplinary effort. A coordinated team approach to inpatient management improves clinical outcome of hospitalized patients. Specific approaches include clinical pathways or carepaths, multidisciplinary stroke programs, and dedicated stroke units.

It is often difficult to generalize from studies which claim benefit with particular approaches. Many were done in diverse health care systems, and it is problematic to apply results to other populations and settings. In many studies which demonstrate benefit with a coordinated approach to acute management, it is unclear whether the benefit arises from the use of a predetermined stroke pathway, available special expertise in stroke treatment, specific interventions such as DVT prophylaxis, or the multidisciplinary approach to patient care.

A formalized approach using a stroke pathway or care-path does appear to be of benefit.16,17,18Stroke pathways and carepaths coordinate a multidisciplinary clinical team and generally include nursing protocols to prevent complications, document clinical course, and address early rehabilitation issues. The role of expert nursing is an important element of this formalized approach. A multidisciplinary stroke team also appears to be beneficial.6 The benefits of such an approach include improved accuracy in the diagnosis of stroke and better resource utilization, as evidenced by shortened hospital length of stay and fewer unnecessary tests. 6,16,17,19

Studies suggest that the care of patients in a geographically designated stroke nursing unit favorably impacts the outcome of acute stroke.6,18,20-24 The benefits of stroke units include reduced long-term mortality and improved functional outcome. Much of the value of a coordinated approach to inpatient management appears to result from specialized nursing care. This is facilitated in a designated stroke nursing unit. Other advantages of such designated units include a commitment of team members to education and early attention to rehabilitation issues.

Fundamental to the coordinated approach to acute management is the involvement of the multidisciplinary stroke team. Team members roles may be identified as follows:

ED Physician

The ED physician is generally the first physician to evaluate the acute stroke patient. In the course of initiating acute evaluation and treatment, the ED physician will usually communicate with the stroke consultant and/or attending physician while the patient is in the ED.

Stroke Consultant

The stroke consultant is usually a neurologist, neurosurgeon, or vascular surgeon. The role of the stroke consultant is to direct evaluation identifying the stroke syndrome, mechanism, anatomy, and pathophysiology, and to recommend appropriate therapy. The stroke consultant is also involved in directing further evaluation, specific therapy, and approaches toward secondary prevention.

Attending Physician

The role of the attending physician is to coordinate all aspects of the patient's inpatient care. This requires close involvement with the nursing staff in addition to the other members of the stroke team. The attending physician has the ultimate responsibility for inpatient management. The attending physician may also be the stroke consultant.

Nursing

Nursing assesses and monitors the patient, provides the specific treatment ordered, and implements specific nursing practices to prevent acute complications. The nursing staff needs to communicate routinely with the stroke consultant and/or attending physician, and needs to notify the attending physician of any significant change in the patient's condition.

Physical Therapy

Physical Therapy, and Rehabilitation Medicine where available, directs progressive mobilization and early rehabilitation. Safety regarding ambulation and fall risk, as well as the long-term rehabilitation plan, is addressed by physical therapy. The physical therapist will therefore need to communicate with nursing, the stroke consultant, and the attending physician.

Discharge Planning

Discharge Planning, along with Rehabilitation Medicine where available, addresses continuity with long-term rehabilitation and secondary prevention, assuring smooth transition to the next setting and level of care. The discharge planner will need to work with the attending physician, stroke consultant, nursing, and physical therapy.

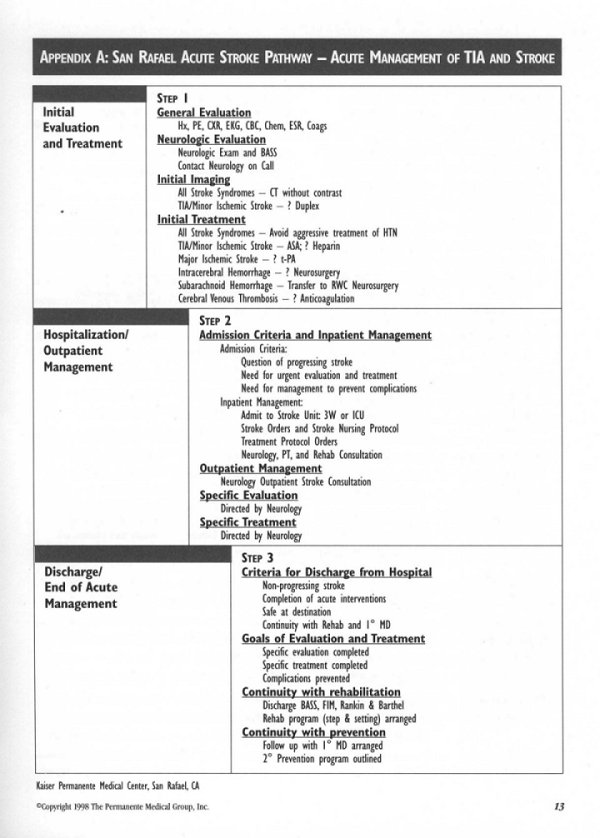

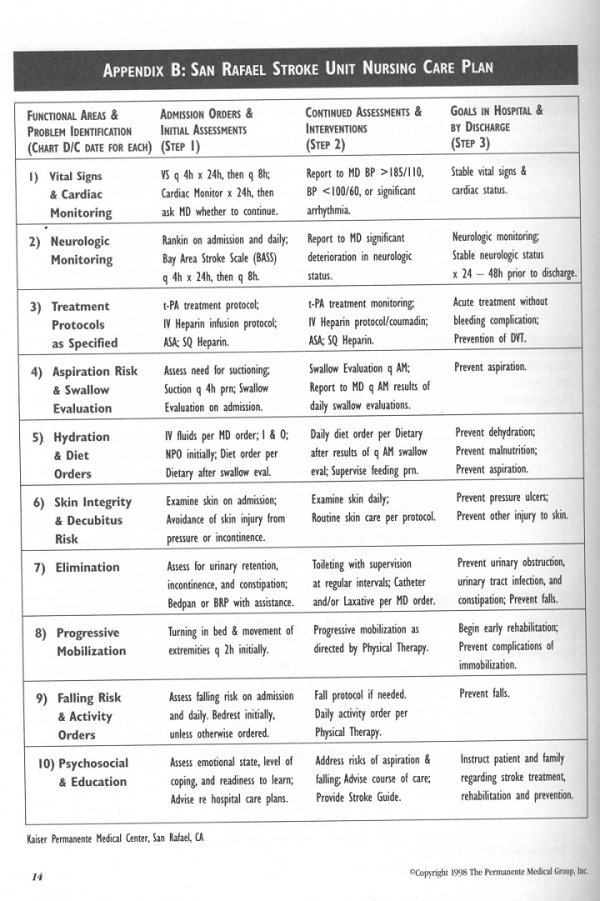

Acute management, particularly inpatient management, of patients with TIA and stroke can be framed in terms of defined goals and roles of a multidisciplinary team. Many inpatient carepaths have been developed and are used successfully to coordinate the multidisciplinary approach. Examples of a general acute stroke pathway and a stroke unit nursing care plan are given in the appendices (pages 13 -14).

RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Whenever possible, acute management of patients with stroke should be provided by a multidisciplinary stroke team. The stroke team should include an ED physician, stroke consultant, attending physician familiar with inpatient management, nursing staff trained in stroke care, physical therapy, and discharge planning. The physician and nursing members of the stroke team should be available and accessible at all times. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) 2. Inpatient management of patients with stroke should be programmatic and formalized with a pathway or carepath which coordinates the multidisciplinary care of the stroke team. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

3. To facilitate nursing expertise for the inpatient management of patients with stroke, the designation of a geographically distinct inpatient stroke unit is recommended where feasible. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

4. Acute evaluation and treatment should generally involve a stroke consultant. Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

5. Measures to prevent complications should be incorporated into the care of patients hospitalized with stroke. These include: bedside swallow evaluation assessing risk of aspiration; maintenance of hydration and nutrition; prevention of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) when prolonged immobility is likely; promotion of early progressive mobilization and prevention of falls; maintenance of skin integrity; avoidance and discontinuation of urinary catheters.

Documentation of these measures and the patient's neurologic status and clinical course should be part of the inpatient nursing record. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

6. A rehabilitation plan should be formulated prior to discharge from acute management. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

7. Patient and family education should be comprehensive and address course of illness, rationale for treatment, prognosis, psychosocial and safety issues, secondary prevention, and, when appropriate, end-of-life issues. Whenever possible, Advanced Directives should be completed and preferences for intensity of care documented. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

8. Stroke team members should participate in continuing education in the management of stroke. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

REFERENCES 1. Cooper R, et al. Slowdown in the decline of stroke mortality in the United States, 1978-1986. Stroke 1990; 21: 1274 - 9. 2. Thorn TJ. Stroke mortality trends: an international perspective. Ann Epidemiol 1993; 3:509 -18. 3. Gresham GE, et al. Post-stroke rehabilitation. Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 16. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. AHCPR Publication No. 95-0662. May 1995. 4 Wade DT, Langton Hewer R. Hospital admission for acute stroke: who, for how long, and to what effect?JEpidemiol Community Health 1985; 39:347 - 52. 5. Henneman PL, Lewis RJ. Is admission medically justified for all patients with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack? Ann Emerg Med 1995; 25:458 -63. 6. Kaste M, et al. Where and how should elderly stroke patients be treated? A randomized trial. Stroke 1995; 26:249 - 53. 7. Davenport RJ, et al. Complications after acute stroke. Stroke 1996; 27:415-20. 8. Goldstein LB. Common drugs may influence motor recovery after stroke. The Sygen in Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Neurology 1995; 45:865 -70. 9.DePippo KL, et al. Dysphasia therapy following stroke: a controlled trial. Neurology 1994 Sept; 44: 1655 - 8. 10.Holas MA, et al. Aspiration and relative risk of medical complica- tions following stroke.Arch Neurol 1994; 51:1051 - 3. 11.HomerJ, et al. Aspiration following stroke: clinical correlates and outcome. Neurology 1988; 38: 1359 - 62. 12.Davalos A, et al. Effect of malnutrition after acute stroke on clinical outcome. Stroke 1996; 27: 1028 - 32. 13.Sandset PM, et al. A double-blind and randomized placebo- controlled trial of low molecular weight heparin once daily to prevent deep-vein thrombosis in acute ischemic stroke. Semin Thromb Hemost 1990; 16 Suppi: 25 - 33. 14.Brandstater ME, et al. Venous thromboembolism in stroke: literature review and implications for clinical practice. ArchPhysMedRehaW 1992; 73 Suppi: 379-91. 15.Hayes SH, Carroll SR. Early intervention care in the acute stroke pnW.Ard}Pl]ysMedRehabil 1986; 67 319-21. 16. Wentworth DA, Atkinson RP. Implementation of an acute stroke program decreases hospitalization costs and length of stay. Stroke 1996; 27: 1040 -3. 17. Odderson IR, McKenna BS. A model for management of patients with stroke during the acute phase. Outcome and economic implications. Stroke 1993; 24: 1823 - 7. 18. Stroke Unit Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative systematic review of the randomized trials of organized inpatient (stroke unit) care after stroke. BrMedj 1997; 314: 1151-9. 19.Alberts MJ, et al. Hospital charges for stroke patients. Stroke 1996; 27:1825-8. 20.Langhome P, et al. Do stroke units save lives? Lancet 1993; 342:395-8. 21.Garraway WM, et al. Management of acute stroke in the elderly: preliminaiy results of a controlled trial. BrMedJ 1980; 280: 1040-3. 22.Strand T, et al. A non-intensive stroke unit reduces functional disability and the need for long-term hospitalization. Stroke 1985;16:29-34. 23.Indredavik B, et al. Benefit of a stroke unit: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 1991; 22: 1026 - 31. 24.Ronning OM, Guldvog B. Stroke units versus general medical wards, 1: twelve- and eighteen-month survival. Stroke 1998; 29:58-62.

APPENDICESThe appendices present examples of an Acute Stroke Pathway and a Stroke Unit Nursing Care Plan developed for use at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Center, San Rafael, California. They are provided as models that can be adapted for use in other acute stroke management care programs.

*Copyright 1998 The Permanente Medical Group, Inc.

MANAGEMENT of BLOOD PRESSURE in ACUTE STROKE

PURPOSE The purpose of this guideline is to address the management of blood pressure in acute stroke. BACKGROUND Blood Pressure in Acute Ischemic Stroke Hypertension has been recognized for decades as one of the most important risk factors for ischemic and hemor- rhagic stroke. There is little doubt that long-term control of elevated blood pressure is beneficial in reducing the risk of both of these types of stroke.1,2However, the treatment of elevated blood pressure in acute stroke involves different considerations, and there are a number of reasons for a cautious and expectant approach rather than attempting to reduce or normalize blood pressure in this setting:

Elevated blood pressure is relatively common in acute stroke, both in patients with pre-existing hypertension and in those without a history of hypertension. A number of studies have demonstrated a tendency for elevated blood pressure to fall without any intervention in the first hours or days after stroke onset.3-6

The threshold for autoregulation of cerebral circulation (the ability of the brain to maintain a constant blood flow over a wide range of blood pressures by constricting vessels as blood pressure rises and relaxing them as blood pressure falls) is raised in chronically hypertensive patients. Optimal blood flow may not be maintained if blood pressure falls below a certain critical level, and this level is substantially higher in hypertensive than in normotensive individuals7-9

Tissues surrounding the area of infarction, the "ischemic penumbra," are tenuously perfused and at risk of perma- nent injury if there is even a minor reduction of local blood supply. In the area of acute ischemic injury, autoregulation is lost and blood flow becomes directly proportional to systemic blood pressure.10-16

There are a number of published cases where acute stroke patients clinically worsened as their blood pressure was aggressively treated, and cases where clinical deficits fluctuated directly with fluctuations of blood 14,17-19

Cerebral perfusion has been demonstrated to be impaired in acute stroke patients with rather mild blood pressure reduction (13 to 16% mean arterial pressure). When this occurs there may be no outward sign that a harmful process is taking place.20

There is at least one report of a possible beneficial effect from using pressors to raise blood pressure in acute stroke patients.21

Treatment of Acute Hypertension in the Setting of Ischemic Stroke

Treatment of hypertension in acute stroke may be indicated in certain very specific circumstances. There may be an increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage in severely hypertensive patients undergoing t-PA infusion for acute stroke.22 Cautious blood pressure control has been suggested if blood pressure rises after institution of treatment with t-PA.23 Elevated blood pressure has also been suggested to be a risk factor for hemorrhage in anti-coagulated patients24

Acute vascular damage and extension of ischemia may occur in the setting of malignant hypertension with hyperten- sive encephalopathy. Malignant hypertension is characterized by papilledema, nephropathy, encephalopathy, microangio-pathic hemolytic anemia, and cardiac failure. In this setting rapid treatment of hypertension is generally recommended.25,26 Other life threatening emergencies, such as acute myocardial infarction or aortic dissection, may also necessitate rapid reductions in blood pressure.26,27

There are no studies showing that urgent reduction of blood pressure in the absence of these specific situations has any beneficial effect. There is also no evidence to support the hypothesis that there is substantial risk of immediate organ damage in leaving elevated blood pressure untreated in the absence of these unusual complications.26-29

Choice of Medications to Manage Blood Pressure in Stroke

In the uncommon situation where it is necessary to reduce blood pressure in acute stroke, there are no controlled studies to indicate the most appropriate medication. However, consideration of the mechanism of action of the various medications used to treat hypertension may provide some guidance.26,30 Alpha- and beta-blockers, ganglionic blockers, and ACE inhibitors have little effect on cerebral vascular tone. Short acting beta-blockers have not been specifically studied in the setting of ischemic cerebrovascular disease and acute hypertension, but offer several theoretical advantages such as ability to titrate blood pressure response, short duration of action, and relative lack of effect on cerebral vascular tone. Labetolol was used in the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) t-PA study for blood pressure treatnent.23 In the case of blood pressure treatment because of acute cardiac ischemia or aortic dissection, the reduction in cardiac output caused by beta-blockers also offers potential cardiovascular benefits.

Nitroprusside offers the advantage of close titration of blood pressure response, but it causes cerebral vasodilatation that may increase intracranial pressure. Since cerebral perfusion pressure is related to the difference between mean arterial pressure and intracerebral pressure, an increase in intracranial pressure may reduce cerebral perfusion pressure. In the case of malignant hypertension or intracerebral hemorrhage (IGH), a further increase in intracranial pressure is probably not desirable. Calcium channel blockers and hydralazine also cause cerebral vasodilatation and have the added disadvantage of a sometimes unpredictable response. Inadvertent overaggressive blood pressure reduction may cause iatrogenic worsening of the ischemic stroke deficit and must be avoided.

There is no rationale for the use of diuretics for acute blood pressure treatment in the setting of acute ischemic stroke. This class of drugs lacks an immediate effect on blood pressure and promotes dehydration, already present in many stroke patients.

Should Blood Pressure Be Raised by Pressors in the Setting of Acute Ischemic Stroke?

There has been one report investigating induced hypertension in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke.21This study demonstrated improvement in some patients whose blood pressure was raised by the use of phenylepherine. There are several anecdotal reports of worsening of ischemic stroke deficit concomitant with blood pressure reduction.14,16-19 Pathophysiologically, one might expect that blood pressure reduction could impair cerebral perfusion, thus worsening the clinical deficit. Therefore, there is some rationale for an induction of a higher blood pressure in the setting of relative hypotension and acute ischemic stroke.

Should Outpatient Antihypertensives Be Continued or Discontinued in the Setting of Acute Ischemic Stroke?

Unfortunately, there are few clinical data and little discussion in review articles to help answer this important question. One recent report studied this question by discontinuing antihypertensive agents in half of a randomized group of patients with hypertension and acute stroke. No difference in outcome between the groups of patients in whom anti-hypertensives were continued or discontinued was observed.31

Vasoactive drugs are often given for reasons other than for reducing blood pressure. For example, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers may be used for treatment of ischemic heart disease as well as hypertension. In this setting, the need to maintain the therapeutic effects of these drugs must be considered in light of possible adverse blood pressure effects. Since prior studies of blood pressure in acute ischemic stroke have sometimes correlated clinical fluctuations with blood pressure fluctuations, the stability of the clinical deficit may also be useful in guiding the decision regarding the continuation of vasoactive drugs.

Management of Blood Pressure in the Setting of Intracerebral Hemorrhage

Marked elevations in blood pressure are common immediately after intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). Enlargement of the area of hemorrhage has been observed in some patients with ICH.32 Whether control of acute hypertension reduces the risk of enlargement of hemorrhage is unknown. As in the case with ischemic stroke, altered autoregulatory thresholds in chronically hypertensive patients, and impaired autoregulation in ischemic brain adjacent to the hemorrhage, are a concern.10

One prospective study evaluated the role of antihypertensive therapy in ICH.33 A positive outcome was reported for treated patients compared to those in whom blood pressure was left untreated. However, the study was unblinded, performed in the pre-CT era, and patients allocated to the treatment arm were clinically far less impaired at onset than those left untreated. Another study retrospectively reviewed the outcome of patients with ICH treated with antihypertensive agents and concluded that those with blood pressures of greater than 145 mean arterial pressure (MAP) had worse outcomes than those with lower blood pressures. However, since attempts were made to control blood pressure in all patients, it is uncertain whether there was a positive effect of treatment. It is possible that uncontrollable blood pressure, even in the face of attempted aggressive therapy, is a marker for a worse prognosis.

At this time, the issue of hypotensive therapy for acute ICH is unresolved. The value of early hypotensive therapy in preventing rebleeding or edema is unknown. As in ischemic stroke, there are concerns of possible ischemic damage with acute blood pressure reductions.

RECOMMENDATIONS 1. In general, urgent treatment of elevated blood pressure in acute ischemic stroke is not recommended. There is no evidence that such treatment is beneficial. There is evidence that such treatment may be harmful. (Research Evidence: Grade C)

2. Several authorities have suggested that treatment of "sustained, extreme" (>220 systolic or >130 MAP) blood pressure elevation is advisable.34 38 Based upon these recommendations, treatment of such sustained, extreme elevated blood pressure may be considered. However, the treating physician should be aware that there are no prospective or retrospective data to support this therapeutic intervention. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

3. There are specific cases where acute reduction of elevated blood pressure is, or maybe, indicated: t-PA treatment of acute ischemic stroke Anticoagulation Malignant hypertension Aortic dissection Acute myocardial ischemia In these conditions, the anticipated benefit of acute blood pressure reduction must be carefully weighed against the risk of potentially worsening the stroke deficit. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

4. If acute reduction of blood pressure is needed, pathophysiologic considerations should guide management. In general, there is no evidence that one antihypertensive is safer than another in this setting, although a titratable and predictable response is desirable. Therefore, consideration should be given to choosing a medication that has the most desirable mechanism of action in the setting in which it is being used. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

5. In a patient who is taking chronic antihypertensive medications, it is uncertain whether such medications should be continued in the setting of acute stroke. If vasoactive medications are being used for a purpose other than hypertension treatment, their continuation should be evaluated in light of the original indication, current blood pressure, and the stability of the stroke deficit. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

6. If there is a suspicion of stroke progression due to relative hypotension, measures to elevate the blood pressure may be considered. Such measures could include discontinuing antihypertensives, fluid resuscitation, supine or Trendelenburg position, or the use of pressors. (Research Evidence: Grade C)

7. Routine treatment of hypertension in ICH is not recommended. Treatment of cases with extremely elevated blood pressure should be considered on a case by case basis with the understanding that the benefits of such treatment are unproven. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

REFERENCES 1. MacMahon S, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part I, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990; 335:765 - 74. 2. Collins R, et al. Blood pressure, stroke and coronary heart diseases. Part 2, Short-term reductions in blood pressure: overview of randomized drug trails in their epidemiological context. Lancet 1990; 335:827 -38. 3. Britton M, et al. Blood pressure course in patients with acute stroke and matched controls. Stroke 1986; 17:861- 4. 4. Carlberg B, et al. Factors influencing admission blood pressure levels in patients with acute stroke. Stroke 1991; 22:527 - 30. 5. Wallace JD, Lavy LL Blood pressure after stroke. JAMA 1981; 246:2177-80. 6. Broderick J, et al. Blood pressure during the first hours of acute focal cerebral ischemia. Neurology 1990; Suppl 40:145. 7. Powers WJ. Cerebral hemodynamics in ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Ann Neurol 1991; 29:231 - 40. 8. Paulson OB, et al. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrwasc Brain Metab ev 1990:2:161-92. 9. Strandgaard S, et al. Autoregulation of brain circulation in severe arterial hypertension. Br MedJ 1973; 1:507 -10. 10. Powers WJ. Acute hypertension after stroke: the scientific basis for treatment decisions. Neurology 1993; 43:461 - 7. 11. Diragi U, Pulsinelli W. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in experimental focal brain ischemia.J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1990:10:327-36. 12. Heiss WD, Rosner G. Functional recovery of cortical neurons as related to degree and duration of ischemia. Ann Neurol 1983; 14:294-301. 13. Siesjo BK. Cerebral circulation and metabolism. JNeurosurg 1984:60:883-908. 14. Waltz AG. Effect of blood pressure on blood flow in ischemic and in nonischemic cerebral cortex: The phenomena of autoregula- tion and luxury perfusion. Neurology 1968; 18:1166 - 9. 15. Astrup J, et al. Thresholds in cerebral ischemia - the ischemic penumbra. Stroke 1981; 12:723 - 5. 16. Hakim AM. The cerebral ischemic penumbra. Can J Neurol Sa 1987; 14:557-9. 17. Britton M, et al. Hazards of therapy for excessive hypertension in acute stroke. Acta Med Scand 1980; 207:253 - 7. 18. Farhat SM, Schneider RC. Observations on the effect of systemic blood pressure on intracranial circulation in patients with cere- brovascular insufficiency. J Neurosug 967;27:441-5 19. Evidente V, Yagnik P. Blood pressure management in acute stroke. Neurology 1996; 46: A256. 20. Lisk DR, et al. Should hypertension be treated after acute stroke? A randomized controlled trial using single photon emission computed tomography. Arch Neural 1993; 50:855-62. 21.Rordorf G, et al. Pharmacological elevation of blood pressure in acute stroke. Clinical effects and safely. Stroke 1997; 28:2133 - 8. 22. Levy DE, et al. Factors related to intracranial hematoma formation in patients receiving tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25:291 - 7. 23. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. EnglJMed 1995; 333: 1581 - 7. 24. Shields RWJr, et al. Anticoagulant-related hemorrhage in acute cerebral embolism. Stroke 1984; 15:426 - 37. 25. Calhoun DA, Oparil S. Treatment of hypertensive crisis. NEngl J Med 1990; 323: 1177 -8. 26. Gifford RWJr. Management of hypertensive crises.JAMA 1991; 266:829-35. 27. Ferguson RK, Vlasses PH. How urgent is 'urgent' hypertension? Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:257 - 8. 28. Ferguson RK, Vlasses PH. Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. JAMA 1986; 255: 1607 -13. 29. Fagan TC. Acute reduction of blood pressure in asymptomatic patients with severe hypertension. An idea whose time has come and gone Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:2169 - 70. 30. Tietjen CS, et al. Treatment modalities for hypertensive patients with intracranial pathology: options and risks. Crit Care Med 1996:24:311-22. 31. Popa G, et al. Stroke and hypertension. Antihypertensive therapy withdrawal. RomJ Neural Psychiatry 1995; 33:29 - 35. 32. Bae HG, et al. Rapid expansion of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurosurgery 1992; 31:35-41. 33. Dandapani BK, at el. Relation between blood pressure and outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 1995; 26:21 - 4. 34. Adams HPJr, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1994; 9: 1901 -14. 35. SpenceJD, Del Maestro RF. Hypertension in acute ischemic strokes. Treat. Arch Neural 1985; 42:1000-2. 36. Lavin P. Management of hypertension in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Arch Intern Med 1986; 146:66 - 8. 37. BillerJ. Medical management of acute cerebral ischemia. Neurol Clin 1992; 10:63 -85. Oppenheimer S, Hachinski V Complications of acute stroke. Lancet 1992; 339:721-4.

ANTICOAGULATION in ACUTE ISCHEMIC STROKE

PURPOSEThe purpose of this guideline is to identify those situations where acute anticoagulation may be appropriate in the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. BACKGROUND Anticoagulation with heparin has long been common management in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Even though convincing clinical trials supporting the value of this treatment have been lacking, this practice has continued in an attempt to forestall clot propagation and to prevent re-embolization. Reviewing existing evidence for the use of heparin, the American Heart Association's (AHA) Stroke Council stated in 1994:

. Because data about the safety and efficacy of heparin in patients with acute ischemic stroke are insufficient and conflicting, no recommendation can be offered... Data about the safety and efficacy of heparin in patients with recent cardioembolic stroke are also too sparse to support a recommendation... There are no data concerning any effects of the vascular distribution of the ischemic symptoms or the underlying vascular disease on the response to heparin... Until more data are avail- able, the use of heparin remains a matter of preference of the treating physician.'

Since this AHA Guideline was written, further studies have cast doubt on the benefit of heparin. What follows includes a brief review of the evidence of heparin's role in three common clinical situations - completed thrombotic stroke, completed cardioembolic stroke, and progressing stroke, or "stroke in evolution."

Anticoagulationfor Completed Presumed Thrombotic Stroke

In 1986, Duke et al. published the first large randomized study of intravenous heparin vs. placebo in 225 patients with acute thrombotic stroked Excluded were patients with suspected cardiac embolism, uncontrolled hypertension, or stroke progression. Treatment was initiated within 48 hours of stroke onset with a target partial thromboplastin time (PIT) between 50 and 70 seconds. Primary outcome measures included progression of neurologic deficit or death within 7 days. There was no statistically significant difference in primary outcomes,and the only significant difference found was an increased death rate at one year in the heparin-treated group.

In 1995 a group from Hong Kong reported a trial involving just over 300 patients with acute ischemic stroke assigned to one of three groups - placebo, high-dose low molecular weight (LMW) heparin given subcutaneously (SQ), or low- dose LMW heparin SQ for 10 days.3 Patients with cardioembolic strokes were not excluded. Primary outcomes were death at 10 days and dependency for activities of daily living at 6 months. By this measure, 45% of high-dose patients had a "poor outcome" compared with 52% of the low-dose patients and 65% of the placebo group.

The International Stroke Trial (IST) randomized nearly 20,000 patients with acute ischemic stroke (with no clear indications for, or contraindications to, heparin or aspirin), to one of six groups: half of the patients received aspirin 300 mg, while half received no aspirin.4 Patients in each of these two groups were assigned one of three heparin regimens: no heparin, 5,000 IU SQ bid, and 12,500 IU SQ bid. Primary endpoints were death from any cause at 14 days and death or disability at 6 months. The higher dose of heparin was associated with a higher rate of serious extracranial bleeding, more hemorrhagic strokes, no reduction in other strokes and hence a significantly higher risk of death or non-fatal stroke within 14 days. Whether patients with atrial fibrillation were included or were separately analyzed, there was no advantage of heparin.5

Preliminary reports from the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) have been disappointing as well. In this study high-dose intravenous heparinoid or placebo were begun within 24 hours of stroke onset. "No difference was found between the treatments at 7 days and at 3 months in the number of patients with a favorable outcome (Glasgow Outcome score I or II and Barthel index of 12 or greater)."6

Anticoagulation for Completed Presumed Cardioembolic Stroke

Many studies of patients with presumed cardioembolic stroke have been published over the past two decades, producing widely-varying estimates of the risk of recurrent embolism in the acute period. At the low end, some studies have found the risk to be 2 to 4%, while others have estimated it to be as high as 20%7 The recently-published 1ST trial found the risk of recurrent stroke to be 4,9% at 14 days in patients with atrial fibrillation who were not assigned to heparin therapy.4 (Note - patients were excluded from the study if the treating physician felt that heparin was clearly indicated.) While there are data indicating that there is a higher risk with some embolic sources than with others (mechanical valves, rheumatic disease, and acute myocardial infarction being more risky than atrial fibrillation),8,9 there seems to be no consensus on the risk of recurrent embolism as compared with the risks and benefits of immediate or early use of heparin in the setting of acute embolic stroke.

The Cerebral Embolism Study Group performed a small randomized controlled study comparing immediate heparinization (bolus and adjusted infusion) with no anti-coagulation or aspirin for 10 days in patients with acute (presumed) cardioembolic strokes.'" Among 24 patients receiving heparin there were no embolic recurrences and no significant hemorrhagic complications. Among the 21 patients receiving no specific therapy there were 2 recurrent strokes - in one patient one week after acute myocardial infarction and in another patient with a known ventricular aneurysm, mural thrombus, and sick sinus syndrome.

The 1ST trial found that patients in atrial fibrillation assigned to heparin had a 2.1% lower incidence of recurrent ischemic stroke at 14 days than those not receiving heparin (2.8% vs. 4.9%), but this was offset by an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke (2.1% vs. 0.4%). Aspirin appeared more beneficial in decreasing the risk of recurrent or hemorrhagic stroke (1% decrease) than did heparin (0.4% decrease).

There are no controlled studies, nor any consensus, on the appropriate timing of heparin when it is used:

Placing emphasis on the studies finding a high risk of re-embolization, there are advocates of immediate heparinization, once a CT scan has ruled out a cerebral hemorrhage.11

The Consensus Conference on Antithrombotic Therapy of the American College of Chest Physicians recommends waiting 2 or 3 days, repeating the CT scan to rule out hemorrhagic transformation, and then administering heparin, followed by warfarin, to non-hypertensive patients with small to moderate-sized infarcts.11When atrial fibrillation is the presumed embolic source, warfarin without initial heparin is recommended.

The Cerebral Embolism Study Group has made similar recommendations and further advises the avoidance of either heparin bolus or over-anticoagulation." Clinical experience suggests that these practices, uncontrolled hypertension, and large-size infarcts are important risk factors for hemorrhagic transformation.

Anticoagulation for Other Stroke Mechanisms There are certain clinical situations, such as arterial dissection, acute large vessel occlusion, or well-defined hypercoagulable states, where many experts favor the use of acute anticoagulation for a stable completed stroke. While there are plausible pathophysiologic reasons to consider this option, in none of these clinical situations has this treatment been tested in a controlled trial.

Anticoagulation for Progressing Stroke or "Stroke in Evolution" Among patients presenting with an acute ischemic stroke, many will show progression of their deficit over the next several days. Aggregate results from several studies indicate that approximately 30% of patients will progress, and there are no reliable clinical predictors of which will do so. 14-17 In an unknown number of patients, progression may be due to factors other than clot propagation or distal embolism, e.g. relative hypotension, local edema, the release of neurotoxins, etc. Heparin has been the traditional therapy in patients with progressive stroke, but there are no controlled studies of its benefit. In uncontrolled experience, heparin failed to stop progression in 21 to 50% of cases where it was given, and was associated with a risk of serious hemorrhage. 18-21 Whether this is better than the natural course in such patients is unknown.

Heparin as Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Prophylaxis Pulmonary embolism accounts for 10% of deaths following stroke' and both leg paralysis and immobility increase the risk for DVT. Low intensity anticoagulation using subcutaneous heparin or LMW heparin is effective in prevent- ing DVT in stroke patients and decreases the risk of death from pulmonary embolism.22,23 Early mobilization and alternating pressure stockings are other strategies to reduce DVT.

Initiation of Oral Anticoagulation When warfarin is initiated, there is a progressive fall in vitamin K-dependent clotting factors, most importantly factors II, VII, X and protein G. The decline of protein C tends to produce a procoagulant effect, while the rapid decrease of factor VII causes a prolongation of prothrombin time days before clinically-significant anticoagulation is accomplished. A recent study has found that initiation of anticoagulation with 5 mg/day of warfarin achieves therapeutic anticoagula- tion at 5 days as well as "loading doses" of 10 mg/day without risking a transitional hypercoagulable state." Furthermore a "stable" dose is achieved much more quickly if one initiates therapy with 5 mg rather than 10mg. 24,25

RECOMMENDATIONS 1. In general, heparin is not recommended in patients with completed thrombotic stroke. There is no persuasive evidence that either therapeutic heparin or LMW heparin is useful in this setting. (Research Evidence: Grade A) 2. In patients with embolic stroke, there is no consensus on the use of heparin: A. Patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation are at lower risk of a second early embolism than other patients with cardioembolic stroke. The initiation of warfarin, without preceding heparin, is suggested for these patients. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus) B. Other patients with high-risk cardiac embolic sources (cardiomyopathy, rheumatic or prosthetic valvular disease, acute myocardial infarction) appear to be at greater risk and may be candidates for heparin, provided hypertension is controlled, there is no hemorrhage on CT, and the infarct is not "large." Because of many clinical variables, and the lack of controlled data, no recommenda- tion can be made regarding immediate heparin vs. a delay of 2 to 3 days. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

3. In patients with progressing stroke, heparin is a reasonable treatment option, but in the absence of controlled data, no firm recommendation can be made. In such patients, consideration should always be given to the possible role of hypotension or other factors in causing the clinical worsening. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

4. In patients with acute arterial dissection, acute large vessel occlusion, occlusion or high-grade stenosis of large vessels, or hypercoagulable states, anticoagulation with heparin and/or coumadin is a reasonable treatment option. However, in the absence of controlled data, no firm recommendation can be made. (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

5. In patients with acute ischemic stroke and either prolonged immobility or significant leg paralysis, early subcutaneous heparin or LMW heparin, and early mobilization, are recommended to reduce the risk of DVT and pulmonary embolism. (Research Evidence: Grade A)

6. When oral anticoagulation is to be initiated, a starting dose of 5 mg/day of warfarin is preferred to larger "loading" doses, (Expert Opinion: Strong Consensus)

REFERENCES 1. Adams HPJr, et al. Guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke. A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke 1994; 9: 1901 -14. 2. Duke RJ, et al. Intravenous heparin for the prevention of stroke progression in acute partial stable stroke. Ann Intern Med 1986:105:825-8. 3. Kay R, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. NEnglJMed 1995; 333:1588 - 93. 4. International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. The International StrokeTrial (IST): a randomized trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischemic stroke. Lancet 1997; 349: 1569 - 81. 5. Lip GY, Beevers DG. Interpretation of 1ST and CAST stroke trials. International Stroke Trial. Chinese Acute Stroke Trial [letter]. Lancet 1997; 350:442 -3. 6. Stroke treatment trials yield disappointing results [comment]. Lancet 1997; 349:1673. 7. Safety of heparin in acute ischemic stroke [letters]. Neurology 1996:46:589-91. 8. Cerebral Embolism Task Force. Cardiogenic brain embolism. The second report of the Cerebral Embolism Task Force. Arch Neurol 1989;46:727 -43. 9. Hart RG, HalperinJL. Atrial fibrillation and stroke - revisiting the dilemmas. Stroke 1994; 25:1337 - 11. 10. Cerebral Embolism Study Group. Immediate anticoagulation of embolic stroke: a randomized trial. Stroke 1983; 14:668 - 76. 11. Chamorro A, et al. Early anticoagulation after large cerebral embolic infarction: a safety study. Neurology 1995; 45:861 - 5. 12. Sherman DG, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for cerebrovascular disorders - An update. Chest 1995; 108 Suppl: 444- 56. 13. Cerebral Embolism Task Force. Cardiogenic brain embolism. Arch Neurol 1986; 43:71 - 84. 14. Jones Hf, Millikan CH. Temporal profile (clinical course) of acute carotid system cerebral infarction. Stroke 1976; 7:64 - 71. 15. Jones HRJr, et al. Temporal profile (clinical course) of acute vertebrobasilar system cerebral infarction. Stroke 1980; 1: 173-7. 16. Britton M, Roden A. Progression of stroke after arrival at hospital. Stroke 1985; 16:629 - 32. 17. Toni D, et al. Progressing neurological deficit secondary to acute ischemic stroke. A study on predictability, pathogenesis, and progress. Arch Neurol 1995; 52:670 - 5. 18. Dobkin BH. Heparin for lacunar stroke in progression. Stroke 1983:14:421-3. 19. Haley EC Jr, et al. Failure of heparin to prevent progression in progressing ischemic infarction. Stroke 1988; 19:10 - 4. 20. Slivka A, Levy D. Natural history of progressive ischemic stroke in a population treated with heparin. Stroke 1990; 21: 1657 -62. 21. Dahl T, et al. Heparin treatment in 52 patients with progressive ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 1994; 4: 101 - 5. 22. Turpie AG, et al. A low-molecular-weight heparinoid compared with unfractionated heparin in the prevention of deep vein thrombosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. A random- ized, double-blind study.Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:353 - 7. 23. Wijdicks EF, Scott JP. Pulmonary embolism associated with acute stroke. Mayo Clin Proc 1997; 72:297 - 300. 24. Harrison L, et al. Comparison of 5-mg and 10-mg loading doses in the initiation of warfarin therapy. Am Intern Med 1997 126:133-6. 25. Warfarin: less may be better [letters]. Am Intern Med 1997; 127: 32-4