ENDORSED BY: CHIEFS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE CHIEFS OF HOSPITAL MEDICINE CHIEFS OF MEDICINE CHIEFS OF PULMONARY MEDICINE

SUMMARY of RECOMMENDATIONS

The recognition of asthma and the assessment of the severity of the exacerbation using pulmonary function testing are fundamental to optimal management of acute asthma.

(NIH guidelines) Treat episodes of acute asthma aggressively

* Maintain oxygen saturation of 90%. (NIH Guidelines)

* Rapidly reverse airflow obstruction by using inhaled beta-agonists and anti-cholinergics. Adding anti-cholinergics to beta-agonists in moderate and severe acute asthma in the ED produces a small, statistically significant improvement in lung function;15,30additionally a trend toward reduced hospitalization has been shown. 11,10 (Grade A)

* Administer oral corticosteroids for moderate or severe exacerbations. Systematic review of 6 RCTs concluded that there was equal efficacy over a range of moderate to high doses of corticosteroids in acute asthma requiring hospital admission.21 (Grade A)

* Use repetitive measures of lung function to assess response to treatment. (NIH Guidelines) Recognize the patient at high risk for life-threatening exacerbation

* Risk factors for death include multiple previous ED visits and hospitalizations, ICU admissions, intubation, high beta-agonist overuse and signs of impending respiratory failure. (NIH Guidelines)

At discharge, intensify therapy and provide a clearly written interim treatment and follow-up plan

* Include oral and inhaled corticosteroids. Combined therapy reduces return ED visits for on-going asthma exacerbations.8,26(Grade B) A short course of oral steroids significantly reduces relapses and decreases beta-agonist use.27 (Grade A)

Arrange for follow-up with asthma care manager or personal physician/nurse practitioner within 7 days

* Asthma self-management education combined with clinical monitoring reduces hospitalization, ED visits, urgent visits, days offwork or school, and nocturnal asthma.12 (Grade A)

For pregnant women with asthma, use similar principles of care

* Maintenance inhaled corticosteroids reduce the risk of an on-going exacerbation without increasing adverse outcomes for mother and child.7,29,33 (Grade B)

Encourage patients to expect future improvement in self-management skills

* With asthma care management, most patients can learn to recognize and avoid their asthma triggers, monitor their condition and adjust their medications to avoid future ED visits and hospitalizations.12 (Grade A).

INTRODUCTION

This guideline is intended for use by physicians and other medical professionals in the acute care, emergency department and hospital setting. It is intended to provide a framework for diagnosing and treating patients who experience acute exacerbations of asthma. In developing these recommendations, KPNC guideline team members reviewed the NHLRBI Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma (NIH guidelines 1997)22 and the CAEP/CTS Asthma Advisory Committee Guidelines for the Emergency Management of Asthma in Adults (Canadian guidelines 1996).4

These national guidelines were developed by expert panels that considered scientific evidence and expert opinion in formulating recommendations. The KPNC guideline team also reviewed subsequently published literature (1997-1999) on selected topics.

A KPNC guideline on outpatient treatment of adult asthma is also available: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Adult Asthma; Kaiser Permanente Northern California, May, 1997.24

EVIDENCE GRADING

Evidence for new guideline recommendations was graded based on the following criteria

* Grade A - Supported by two or more well designed randomized clinical trials

* Grade B - Supported by a single well-designed randomized clinical trial or by two or more non-randomized clinical trials (case-control or cohort)

* NIH Guidelines - Supported by the NHLBI Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma22 which are based on expert panel review of scientific evidence where available and expert panel opinion where evidence is lacking DEFINITION of ASTHMA

Asthma, whatever the severity, is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways. Airway inflammation contributes to airway hyper-responsiveness, respiratory symptoms, disease chronicity and airflow limitation, including acute bronchoconstriction, airway edema, mucus plug formation, and airway wall remodeling. These features lead to bronchial obstruction.22,24

DIAGNOSIS of ASTHMA

To establish a diagnosis of asthma, the clinician determines that:* Episodic symptoms of airway obstruction arepresent

* Airflow obstruction is at least partially reversible (rarely, long-term monitoring may be required to document reversibility)

* Alternate diagnoses that can mimic asthma are excluded (e.g. pulmonary embolism, heart disease, anemia, emphysema, chronic bronchitis)22,24

OCCULT ASTHMA

The diagnosis of asthma is frequently missed. The most common incorrect diagnosis is bronchitis. Improved diagnosis depends upon:

*A high index of suspicion. Asthma often presents as persistent cough or URI that does not respond to usual treatment.

*Routine use of objective measures (peak flow and/or spirometry)

Consider asthma if the patient answers "yes'' to any of the following:

*Do you have a troublesome cough at night?

*Do your colds usually "go to the chest" or take more than ten days for the cough to clear up?

*Have you had recurrent diagnoses of "bronchitis."

*Do you have a cough or wheeze after exercise?

*Have you ever had an episode or recurrent episodes of wheezing?

*Do you have a cough, wheeze or chest tightness after exposure to airborne allergens or pollutants?

*Do you use anti-asthma medication (e.g., over-the counter inhaler or family member's inhaler)?

*Does anyone in your immediate family have asthma?

*Do you have a personal history of allergic rhinitis, sinusitis or atopic dermatitis?22,24

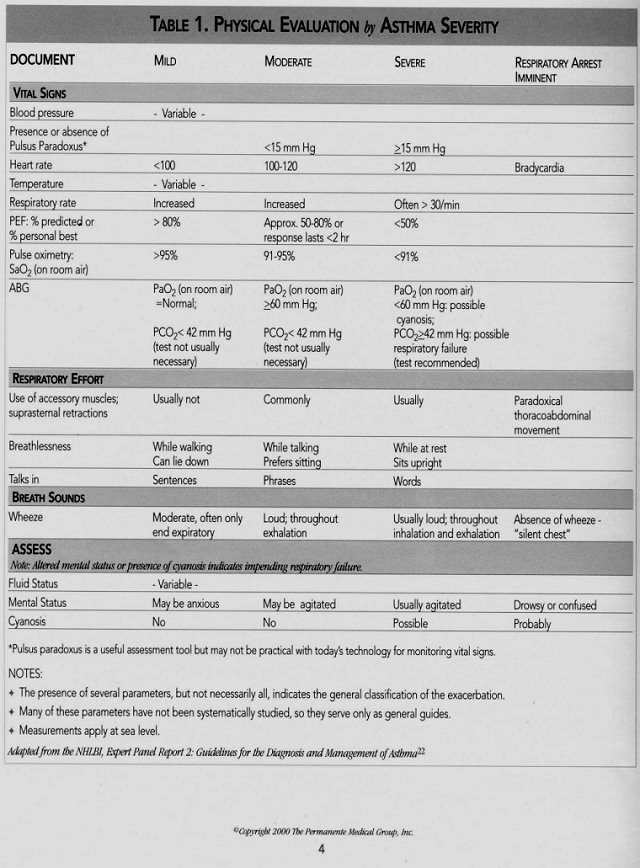

EVALUATION Important elements of physical examination Assess and document signs and symptoms in Table I, page 4.

Elements of brief history

* Onset and severity of symptoms

*Triggers/precipitating illness

* Presence or absence of upper airway obstruction

* Current medications

* Recent best peak flow - from patient report, diary or medical chart

* Presence or absence of written self-management plan

* Prior hospitalizations, ED visits for asthma, particularly in last year

*Prior mechanical ventilation, intubation

* Co-morbidities, especially pulmonary or cardiac disease or those which would be aggravated by systemic corticosteroid therapy (diabetes, peptic ulcer, hypertension, and psychosis)

*Smoking history and/or exposure: personal and household members

Recognize the patient with risk factors for life-threatening exacerbation

* History of sudden severe exacerbation

* History of multiple ED visits or hospitalizations in the previous year

* Prior admission for asthma to an intensive care unit, prior intubation

* High beta-agonist use (greater than two canisters per month)

* Current use of systemic corticosteroids or recent withdrawal from systemic corticosteroids

* Co-morbidities, as from cardiovascular diseases or COPD

* Difficulty perceiving airflow obstruction or its severity Laboratory studies - consider:

* Arterial blood gas (ABG) if patient is failing in his/her respiratory effort, in severe distress or experiencing altered mental status

* Complete blood count (CBC)* Serum theophylline concentration, if indicated

* Serum electrolytes in patients taking diuretics regularly, or with cardiovascular disease or diabetes

* Chest radiography in patients who have complicating cardiopulmonary process (chest radiography is generally not necessary in uncomplicated asthma)3,34,35

* Electrocardiograms in patients older than 50 with coexistent heart disease, arrhythmia or COPD

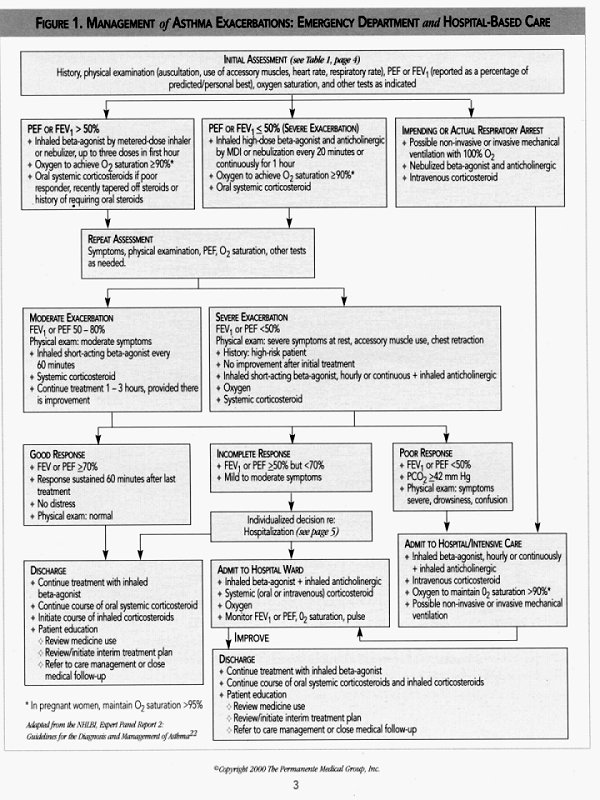

TREATMENT-TAILORED to SEVERITY of EXACERBATION

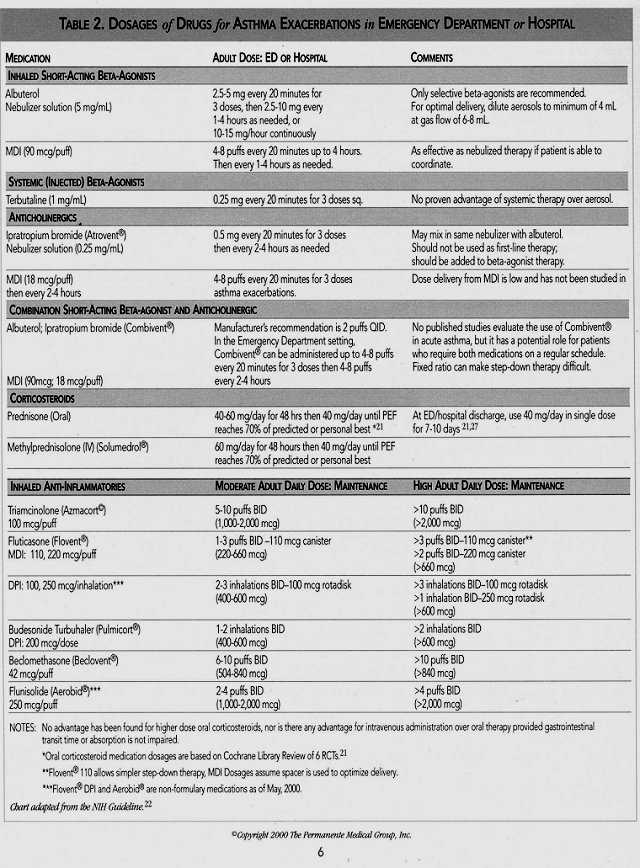

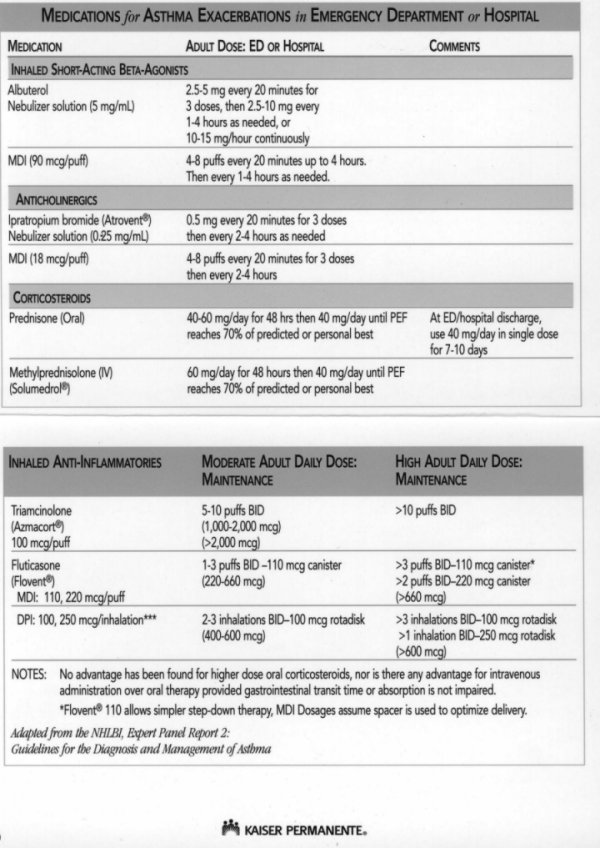

Inhaled short-acting beta-agonists

* Most effective means of reversing airflow obstruction

* In patients with moderate and severe disease, initial treatment is beta-agonist every 20 minutes for one hour with reevaluation

* Because of risk of cardiotoxicity, use only selective beta-agonists (albuterol) in high doses

* Equivalent bronchodilation can be achieved by metered dose inhaler (MDI) with spacer/holding chamber. Nebulized therapy is appropriate in patients who cannot coordinate inhalation with an MDI5

* In severe exacerbations, albuterol can be given up to 15 mg/hr via continous nebulization, but the patient must be on a cardiac monitor for potential cardiac arrhythmias and checked frequently for hypokalemia

Anticholinergics

* Anticholinergics should be added to initial treatment of moderate and severe exacerbations10,11,15,17,30

* Subsequent doses of ipratropium can then be given: 4 puffs every 4-6 hours

Systemic corticosteroids

* For patients who have moderate-to-severe exacerbations and patients who do not respond completely to initial beta-agonist therapy

* Recommended regimen is oral prednisone 40-60 mg/day (alternative is IV methylprednisolone 60 mg/day), then 40 mg/day until PEF reaches 70% of predicted or personal best21

Inhaled corticosteroids

* Initiate or continue inhaled corticosteroids in all moderate to severe asthma patients at discharge1,8,23,25,31

Oxygen

*Maintain an SaO2, >90 percent (>95% in pregnant women and in patients with coexistent heart disease). Monitor oxygen saturation until a clear response to bronchodilator therapy has occurred

Antibiotics

Antibiotics - May be necessary for co-morbid conditions (sinusitis, bronchitis) but not usually recommended for treatment

Copyright 2000 The Permanente Medical Group, Inc.

MEDICATIONS USED IN CHRONIC MAINTENANCE

* Methyixanthines (theophylline, aminophylline) - In patients currently using methyixanthines, it may be appropriate to continue

* Leukotriene modifiers (montelukast, zafirlukast)- Non-formulary medications usually initiated and monitored by asthma specialists for moderate to severe asthmatics, leukotriene modifiers may modify the length and severity of future asthma exacerbations but there is no evidence of benefit for acute treatment13,14,16,20

* Long-acting beta-agonists (salmeterol) - Similarly, no evidence of benefit for acute asthma (Consensus of the KPNC expert group)

REPEAT ASSESSMENT

* Make repeat assessments after initial and third dose of combined inhaled bronchodilator and anticholinergic (approximately 60-90 minutes after initiating treatment)

* If not improving, remember to evaluate and treat for complicating conditions such as sinusitis, upper airway obstruction (e.g. obstructive sleep apnea), GERD, pneumonia

DECISION to DISCHARGE from the EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

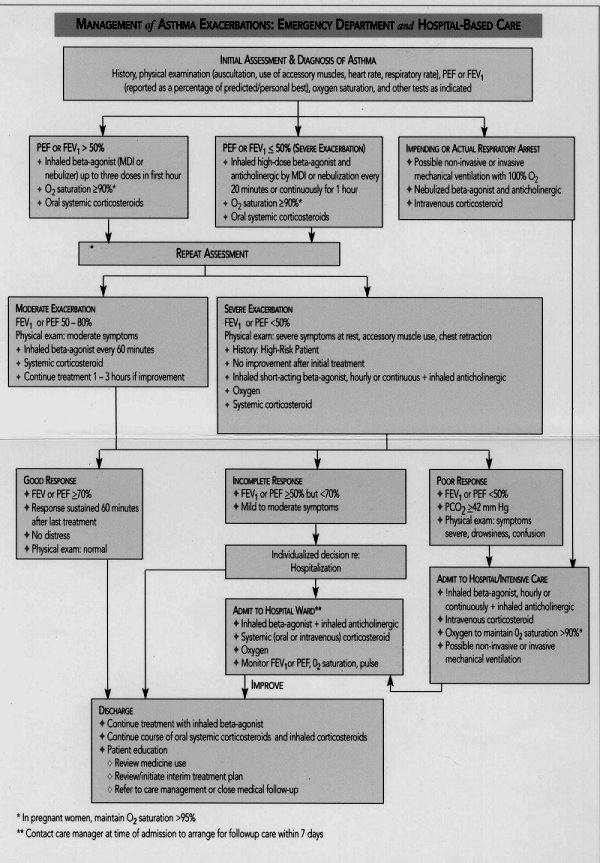

* Dependent on response to treatment (see Figure I, page 3)

* Prescribe sufficient medications to continue treatment after discharge

* Demonstrate proper metered dose inhaler and spacer technique

* Prescribe a peak flow meter and demonstrate proper technique

* Provide written interim treatment plan and advise to avoid asthma triggers

* Emphasize need for continual, regular care in an outpatient setting: appoint patient for followup with asthma care manager or personal physician within seven days

* Provide instruction on returning for care if symptoms worsen

* Provide information about the KPNC Asthma Care Management Program

HOSPITALIZATIONS See figure I, page 3

Indications for hospitalization

* Severe distress or impending respiratory arrest

* Severe airflow obstruction despite treatment with beta-agonists, inhaled and systemic corticosteroids and anti-cholinergics (peak flow <50%andPCO2>42)

* Need for supplemental O2 to maintain 02 saturation of 90% 4- Prior history of similar, severe, complicated exacerbations

The principles of hospital care for asthma

* Continue oxygen

* Continue inhaled bronchodilators and anticholinergics

* Continue systemic corticosteroids. Initiate or continue inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Use MDIs and spacers in the hospital to encourage compliance after discharge

* Frequent assessment, including clinical assessment of respiratory distress and fatigue,objective measurement of airflow (PEF, FEV1). Monitor oxygen saturation

Provide patient education.

The hospital setting may make patient more receptive and provides a unique opportunity to review patient understanding of:

* Causes of asthma exacerbation

* Purposes and correct uses of discharge medications and peak flow measurements

* Importance of follow-up and continuing care

* Actions to be taken for worsening symptoms or peak flow values

* Asthma education resources such as care management, classes and clinics

CRITERIA and RECOMMENDATIONS for IMPENDING RESPIRATORY FAILUREMost patients respond well to therapy. A small minority shows signs of worsening ventilation.

Signs of impending respiratory failure include:

* Declining mental clarity

* Altered consciousness, coma

* Worsening fatigue with declining respiratory rate

* PCO2 of >42 mm Hg

* pH<7.30-7.35

* Respiratory rate > 35

* Respiratory rate rapidly declining

Some patients may benefit from assisted ventilation2,23

* Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation ("Bi-PAP") may benefit alert patients who are not responding to pharmacological intervention, who have hypercapnic respiratory failure and are not in immediate need of intubation

* Invasive Ventilation: In patients with altered mental status/coma, mechanical ventilation with intubation is required.

When to intubate * Decision to intubate has subjective and objective considerations

* Once determined to be necessary, intubation should not be delayed

* Patients presenting with coma and signs of impending respiratory failure should be intubated immediately

* Best performed semi-electively if possible; before the crisis of respiratory arrest

Key principles of invasive mechanical ventilation6,32

* Avoid barotrauma and pneumothorax. Attempt to keep plateau pressures low: not over 40

* Utilize permissive hypercapnia: allow CO2 to rise, pH to drop, keep respiratory rate low. Bicarbonate drip should be considered to keep pH at 7.2 or above

* Use sedation and paralysis to prevent spontaneous ventilation

Recognize patients at highest risk for recurrence. Interventions may include brief, intensive educational intervention in the hospital prior to enrollment in care management program. Risk factors include:

<>Difficulty in accepting a chronic disease diagnosis and following a self-management plan

<> Difficulty mastering asthma skills including peak flow monitoring, and metered dose inhaler and spacer technique <> Non-adherence to medication regimens

<> Inability to control exposure to environmental triggers

<> Discharge medication should include short acting inhaled beta-agonist and sufficient oral and inhaled corticosteroids to ensure that patients continue their treatment plan until their follow-up visit

<> Administer pneumovax per vaccination guidelines and/or influenza vaccine (annually October-March) on morning of discharge

<> Use of home nebulizer treatments is discouraged. MDIs are preferable to home nebulizers in terms of cost, mobility and prevention of tachyphylaxis

<> Review or develop a written interim treatment plan

<> Prescribe peak flow meter and review how to use it

<> Assess follow-up needs and refer patients to primary care, care management, or specialty care as appropriate

ACUTE ASTHMA DURING PREGNANCY

*Asthma exacerbations during pregnancy are common

*Neonatal outcomes are superior when maternal symptoms are controlled and oxygenation and pulmonary function are optimized, yet under treatment with corticosteroids is often observed, leading to an increased likelihood of ongoing exacerbation7,33

* Pregnancy is not a contraindication to use of inhaled beta-agonist or inhaled or systemic steroids

* Maintenance treatment with inhaled anti-inflammatories during pregnancy reduces the risk of asthma exacerbation 29,33

* Rapid therapeutic intervention at the time of an exacerbation is imperative to prevent impaired maternal and fetal oxygenation. In addition, oxygen saturation should be maintained at greater than 95%18

* Principles for managing asthma exacerbations during pregnancy are similar to those for general management: repetitive lung function measurements, therapy with repeat doses of inhaled beta-agonists, early administration of systemic corticosteroids, discharge on inhaled corticosteroids.18,26

* Notify obstetrician of the ED visit and coordinate close follow-up.

FOLLOW-UP CARE

The hallmark of effective asthma treatment is patient understanding of asthma triggers and ability to intervene with appropriate beta-agonist and anti-inflammatory medications using the "step-wise approach" to medication adjustment based on a self-management plan. Set the expectation that most patients can learn to recognize and avoid their asthma triggers, monitor their condition and adjust their medications to avoid or intervene early in the course of a future exacerbation. Also, remind patients that the high dose corticosteroids they are using immediately post ED and hospital visits will be adjusted downward over time during their follow-up care.

The KPNC Adult Asthma Care Management Program offers:

* Proactive outreach to asthmatic members after ED and hospital visits

* Comprehensive follow-up evaluation including confirming diagnosis, pre- and post- bronchodilator spirometry, educational needs assessment and appropriate referrals

* Clinical monitoring and medication adjustment

* Individual and group asthma education Asthma care manager services are provided in all KPNC service areas in a combination of individual and group settings.

REFERENCES 1. Afilalo M, Guttman A, Colacone A, et al. Efficacy of inhaled steroids (beclomethasone dipropionate) for treatment of mild to moderately severe asthma in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial Ann EmergMed 1999;33(3):304-9.

2. Antonelli M, Conti G. Rocco M, et al. A comparison of non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation and conventional mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure. NEnglJMed 1998; 339(7):429-35.

3. Aronson S, Gennis P, Kelly D, et al. The value of routine admission chest radiographs in adult asthmatics.Ann EmergMed 1989;18:1206-1208.

4. Beveridge RC, Grunfeld AF, Hodder RV, et al. Guidelines for the emergency management of asthma in adults. CAEP/CTS Asthma Advisory Committee. Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians and the Canadian Thoracic Society. CMAJ 1996;155(1):25-37.

5. Cates Cj. Rowe BH. Holding chambers versus nebulisers for beta-agonist treatment of acute asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. 1999, Issue 4.

6. Corbridge TC, HallJB. The Assessment and management of adults with status asthmaticus. AmJRespir Crit CareMed 199;:151:1296-1316.

7. Cydulka RK, Emerman CL, Schieiber D, et al. Acute asthma among pregnant women presenting to the emergency department. ArnJRespir Crit CareMed 1999;l60:887-892.

8. DonahueJG, Weiss ST, LivingstonJM, et al. Inhaled steroids and the risk of hospitalization for asthma. JAMA 1997;277(l 1): 887-891.

9. Edmond SD, Carmago CA, Nowak RM, et al. 1997 National asthma education and prevention program guidelines: A practical summary for emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:579-589.

10. Fitzgerald JM, Grunfeld A Pare PD, et al. The clinical efficacy of combination nebulized anticholinergic and adrenergic bronchodilators versus nebulized adrenergic bronchodilator alone in acute asthma. Chest 1997;lll:311-15.

11. GarrettJE, Town Gl, Rodwell P, et al. Nebulised salbutamol with and without ipratropium bromide in the treatment of acute asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;100:165-70.

12. Gibson PG, Coughlan J, Wilson AJ, et al. Self- management education and regular practitioner review for adults with asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. 1999, Issue 4.

13. Israel E, Cohn J, Dube L, et al. Effect of treatment with zileuton, a 5-lipoxygenase inhibitor, in patients with asthma. A randomized controlled trial. Zileuton Clinical Trial Gmup.JAMA 1996; 275(12):931-6.

14. Kemp, JP, Mikwitz, MC, Bonuccelli CM, et al. Therapeutic effect of zafirlukast as monotherapy in steroid-naive patients with severe persistent asthma. Chest 1999;115:336-342.

15. Lanes SF, GarrettJE, WentworthCE 3rd, et al. The effect of adding ipratropium bromide to salbutamol in the treatment of acute asthma: a pooled analysisofthreetrials. Chest 1998;114(2): 365-72.

16. Lofdahl, C-G, Reiss, TF, et al. Randomised, placebo controlled trial of effect of a leukotriene receptor antagonist, montelukast, on tapering inhaled corticosteroids in asthmatic patients. BMJ 1999;319:87-90.

17. Lin RY, Pesola GR, Bakalchuk L, et al. Superiority of ipratropium plus albuterol over albuterol alone in the emergency department management of adult asthma: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med1998;31:208-213.

18.Luskin, AT. An overview of the recommendations of the Working Group on Asthma and Pregnancy. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999; 103(2Pt2):S350-3.

19.McFadden, ER, Casale T, Edwards T, et al. Inhaled glucocorticoids and acute asthma: therapeutic breakthrough or nonspecific effect? Am JRespir Crit Care Mod 1998;157:677-678.

20.Malmstrom, KM, Rodriguez-Gornez, G, GuerraJ, et al. Oral montelukast, inhaled beclomethasone, and placebo for chronic asthma: A randomized controlled trial. AnnIntMed 1999;130:487-495.

21.Manser R, Reid D, Abramson M. Corticosteroids for acute severe asthma in hospitalized patients (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library 1999, Issue 4.

22.NHLBI Expert Panel Report 2: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. National Institutes of Health 1997, Pub No 97-4051.

23.Pauwels RA, YemaultJC, Demedis MG, et al. Safety and efficacy of fluticasone and beclomethasone in moderate to severe asthma. AmJReespir Crit Care Med 1998;157:827-832.

24.The Permanente Medical Group. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Adult Asthma. Kaiser Permanente Northern California, May, 1997.

25.Raphael GD, Lanier RQ, BakerJ, et al. A comparison of multiple doses of fluticasone and beclomethasone in moderate to severe asthma.J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103(5Ptl):796-803.

26.Rowe BH, Bota GW, Fabris L, et al. Inhaled budesonide in addition to oral corticosteroids to prevent asthma relapse following discharge from the Emergency Department. A randomized controlled trial.JAMA 1999;281(22):2119-2126.

27.Rowe BH, Spooner CH, Ducharme FM, et al. Corticosteroids for preventing relapse following acute exacerbations of asthma (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. 1999, Issue 4.

28.Singh, AK, Woodruff, PG, Ritz, RH, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: Are ED visits a missed opportunity for prevention? Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:144-147.

29.Stenius-Aarniala BS, HedmanJ, Teramo KA, et al. Acute asthma during pregnancy. Thorax 1996; 51:411-414.

30.Stoodley, RG, Aaron, SD, Dales, RE. The role of ipratropium bromide in the emergency management of acute asthma exacerbation: A metaanalysis of randomized clinical trials. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 34(l):8-18.

31.Szefler SJ, Boushey HA, Peariman DS, et al. Time of onset of effect of fluticasone propionate in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999:103 (Pt l):780-8.

32.lhxen DV. Permissive hypercapnic ventilation. AmJRespir Crit CareMed 1994;150:870-4.

33.Wendel PJ, Ramin SM, Bamett-Hamm C, et al. Asthma treatment in pregnancy: a randomized controlled study. AmJObstetGynecol 1996; 175(l):150-4.

34.White CS, Cole RP, Lubetsky HW, et al. Acute Asthma: Admission chest radiography in hospitalized adult patients. Chest 1991; 100(1): 14-16.

35. Zieverink SE, Harper AP, Holden RW, et al. Emergency room radiography of asthma: An efficacy study. Radiology 1982:145:27-29.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Clinical Leader Kenneth Greene, MD, Medicine; Santa Clara Work Group Tom Dailey, MD, Pulmonary Medicine;Santa Clara Charlotte Edwards, RN; TPMG Department of Quality & Utilization (DOQU) Yolanda Mawson, RN, Care Coordination; Sacramento Julie Nack, PharmD, Pharmacy; Fairfield Joseph Robinow, MD, UM Chief; Vallejo Paul Roggero, MA, Respiratory Care;San Francisco Andrea Wagner, MD, Emergency Medicine;San Francisco Project Management Laura Skabowski, MS; DOQU Kathleen Martin; DOQU Data Analysis Carol Remmers, MPH; DOQU Maqdooda Merchant, MS/MA; DOQU Betsy Stone, DrPH; DOQU Graphic Design Gail Holan; Curvey Graphic Design This guideline was reviewed by over 40 physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, phamiacists and other medical professionals representing a variety of departments from all facilities. For a complete list of reviewers, see the on-line version at http:/cl/kp.org

CONTACT INFORMATION Kaiser Permanente Northern California TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization 1800 Harrison Street, 4th Floor Oakland, CA 94612 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950

To obtain more information about KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines, printed copies, or permission to reproduce any portion, please contact the TPMG Dept. of Quality & Utilization, or send an e-mail message to clinical.guidelines@kp. org KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines and implementation tools can be viewed on-line on the Kaiser Permanente Northern California intranet at http://cl.kp.org CME Credit. Continuing Education Credit for physicians and nurses is available for review of this guideline. The CME Pre-Test and Post-Test is available on-line at http://cl.kp.org or by calling 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950.

This website is accessible only from the Kaiser Permanente computer network. Disclaimer

The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) Clinical Practice Guidelines have been developed to assist clinicians by providing an analytical framework for the evaluation and treatment of selected common problems encountered in patients. These guidelines are not intended to establish a protocol for all patients with a particular condition. While the guidelines provide one approach to evaluating a problem, clinical conditions may vary significantly from individual to individual. Therefore, the clinician must exercise independent judgment and make decisions based upon the situation presented.

While great care has been taken to assure the accuracy of the information presented, the reader is advised that TPMG cannot be responsible for continued currency of the information, for any errors or omissions in this guideline, or for any consequences arising from its use.

Copyright 2000 The Permanente Medical Group, Inc.

BACK to Kaiser Diagnostic and Treatment Documents Index