In Copyright Since September 11, 2000 Help for Kaiser Permanente Patients on this public service web site. Permission is granted to mirror if credit to the source is given and the material is not offered for sale. The Kaiser Papers is not by Kaiser but is ABOUT Kaiser | PRIVACY POLICY ABOUT US| CONTACT | WHY THE KAISERPAPERS | MCRC | Why the thistle is used as a logo on these web pages. |

Kaiser Diagnostic and Treatment Documents

TPMG Clinical Practice Statement Management of Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease MAY 1999ENDORSED BY CHIEFS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE CHIEFS OF MEDICINE CHIEFS OF PULMONOLOGY HOSPITAL BASED SPECIALISTS PEER GROUP

CLINICAL PRACTICE STATEMENT

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE EXACERBATIONS of CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE

As described by the American Thoracic Society', an acute exacerbation of COPD is characterized by an acute worsening of symptoms accompanied by worsened lung function in an individual with COPD. In the most severe of instances, an acute exacerbation poses the risk of acute respiratory failure. Potential precipitants of such acute exacerbations include: various infections (viral and bacterial), fluid overload, thromboemboli, cardiac ischemia, aspiration, excessive sedation from medications, and bronchospasm.

INITIAL EVALUATION and ADMISSION CRITERIA KEY COMPONENTS of INITIAL EVALUATION * History: baseline respiratory status, sputum volume and characteristics, duration and progression of symptoms, severity of dyspnea, exercise limitations, sleep and eating difficulties, home care resources, failure of home regimen, symptoms of co-morbid acute or chronic conditions, smoking history * Physical examination: respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature, pulse, bronchospasm, altered mentation, paradoxical abdominal retractions, use of accessory respiratory muscles, acute morbid conditions * Laboratory: usually includes ABG, BUN/Cr, Lytes, Glu, CBC, Chest radiograph if pneumonia is suspected, ECG, pulse oximetry, theophylline level if outpatient theophylline is used

CONSIDERATION for ADMISSION The severity of the condition (by the high association with near and long-term mortality rates) should be factored in when considering admission for patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD. The following variables are significant predictors of COPD short-term mortality 4,5,6,7. * Age > 65 * Alveolar arterial oxygen gradient > 41mm Hg * Ventricular arrhythmia * Atrial fibrillation * CHF * Presence of cor pulmonale * Prior functional status

Note: Other significant predictors of short term mortality included the APACHE III score (Abnormal values over a 24 hr period of the following: Glasgow Coma score, heart rate, mean blood pressure, temperature, hematocrit, WBC count, creatinine, urine output, serum urea nitrogen, sodium, albumin, glucose, respiratory rate, pH, PaCO2 PaO2) and a low body mass index.

ADDITIONAL INDICATIONS for HOSPITALIZATION1 * Inadequate response of symptoms to outpatient management * Inability to eat or sleep due to dyspnea * Prolonged, progressive symptoms before emergency visit * Planned invasive surgical or diagnostic procedure requiring analgesics or sedatives that may worsen pulmonary function * Co-morbid condition such as severe steroid myopathy or acute vertebral compression fractures, with worsening pulmonary function

POTENTIAL INDICATIONS for ICU ADMISSION1 * Severe dyspnea that responds inadequately to initial emergency therapy * Confusion, lethargy, or respiratory muscle fatigue (the last characterized by paradoxical diaphragmatic motion) * Persistent or worsening hypoxemia despite supplemental oxygen or severe worsening of respiratory acidosis (pH < 7.30) * Assisted mechanical ventilation is required

TREATMENT FOR AN ACUTE EXACERATION of COPD The principal goal of COPD management is to achieve and maintain control of the disease. This includes improving symptoms and quality of life and reducing the frequency and severity of COPD exacerbations; improving lung function and reducing the accelerated decline in lung function; preventing and effectively treating complications; reducing mortality; and avoiding or minimizing treatment side effects. Based on review of recent literature the guideline team recommends the following approach:

* Oxygen therapy: The most important consequence of hypoxemia is tissue hypoxia. Hence, the first responsibility of the physician is to correct or prevent life threatening hypoxemia. Continued monitoring is highly advisable in the unstable patient. The goal of oxygen therapy is correction of hypoxemia to a PaO2 > 60mm Hg or 02 Sat > 90%.

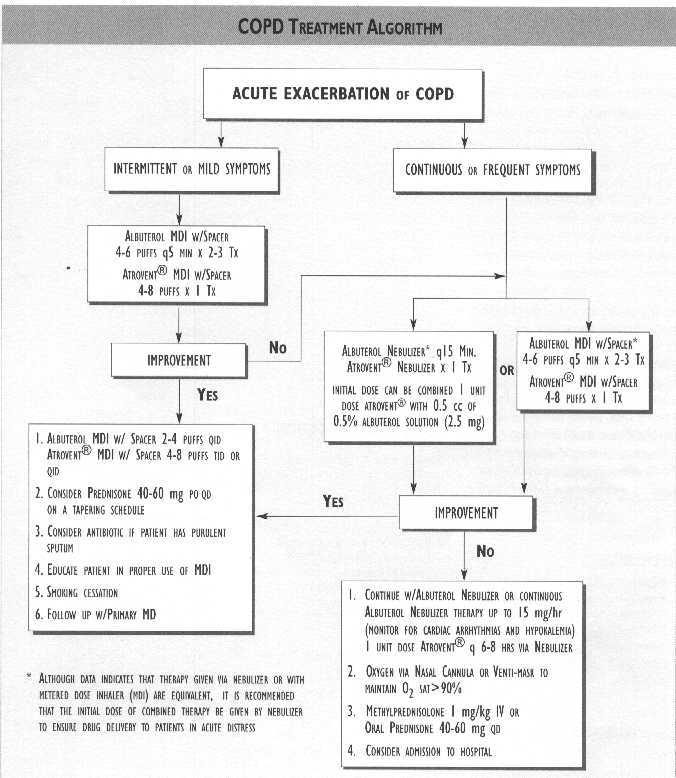

* Combination therapy with a beta2-agonist (albuterol) and anticholinergic aerosols (Atrovent“ or its generic equivalent, ipratropium bromide) should be considered the next step in the inpatient management of acute COPD exacerbations. There is evidence to suggest that they may act synergistically with no increase in adverse effects due to combined usage8,9,10,11 Although data indicates that therapy given via nebulizer or with metered dose inhaler (MDI) are equivalent12,13 it is recommended that the initial dose of combined therapy be given by nebulizer to ensure drug delivery to patients in acute distress. Nebulized beta2-agonist (albuterol) can be given every 15 minutes or until the patient's clinical condition changes. In severe exacerbations,continuous nebulized beta2-agonist (albuterol) can be given up to 15 mg/hr, but the patient must be carefully monitored for cardiac arrhythmias and hypokalemia. Subsequent doses of Atrovent“ can then be given every 6-8 hours. Patients can then be switched to MDI (albuterol 2-4 puffs with spacer QID, Atrovent“ 4-8 puffs TID or QID) once considered stable. Patients presenting to the clinic or emergency department in mild respiratory distress can often be treated with an inhaled beta2- agonist (albuterol) MDI with spacer 4-6 puffs every 5 minutes for two to three treatments combined with one treatment of 4-8 puffs Atrovent MDI with spacer. If there is no significant clinical improvement, the patient can then be given an albuterol/Atrovent“ nebulizer therapy [Initial dose can be combined: I unit dose Atrovent“ with 0.5 cc of 0.5% albuterol solution (2.5 mg)].

* Oral or intravenous corticosteroids should be considered to decrease airway inflammation. Studies14,5,6,7 have shown patients treated with corticosteroids have rapid improvement ofFEV1, decreased rate of relapse, fewer treatment failures, better spirometry, and shorter length of stay. The amount and duration of corticosteroids given to patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD is unclear, and is currently under clinical investigation. However, patients requiring hospitalization may benefit from Methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg every 6 hours for 2-3 days and then followed by prednisone 40-60 mg per day on a tapering schedule. Patients not requiring hospitalization may also benefit from prednisone 40-60 mg/day on a tapering schedule.

* Purulent sputum usually provides rationale for a course of antibiotic therapy: amoxicillin, trimethoprim-sulfa, cephalosporins, or macrolides may be chosen. It has been shown that such agents may assist in resolving an exacerbation, but they have more value in decreasing the risk of further deteriorationl8 More recently a meta-analysisl9 demonstrated a small but significant improvement in peak expiratory flow due to antibiotic therapy in patients with exacerbations of COPD.

* The roles of theophylline or intravenous aminophylline have diminished significantly in the setting of an acute exacerbation of COPD because of their toxic effects and little proof of efficacy when combined with other bronchodilators20,21 and are not recommended in the management of acute COPD exacerbations.

Other treatment & evaluation considerations during the hospital phase may include: * Sedation and pain management * Ambulation or DVT prophylaxis as applicable * Respiratory Therapist evaluation * Non Invasive Ventilation per protocol * Implementing COPD pathway as applicable * Discharge care planning

DISCHARGE CRITERIA for PATIENTS WITH ACUTE EXACERBATIONS of COPD

Insufficient clinical data exists to establish the duration of hospitalization in individual patients to achieve maximal benefit. Consensus and limited data support the discharge criteria listed below: 1

* Inhaled bronchodilator therapy is required no more frequently than q 4 h

*

Patient, if previously

ambulatory, is able

to walk across room

*

Patient is able to eat and sleep without frequent

awakening by dyspnea

*

Reactive airway disease, if present, is stable

*

Patient has been clinically stable, off parenteral

therapy, for 12-24 h

*

02 Sat > 88% with or without oxygen

and no significant increase in PaCo2

*

Patient (or home caregiver) fully understands

correct use of medications

*

Follow-up and home care arrangements have been

completed (e.g., checking and

updating

immunization status; referral to COPD case manager

as applicable; visiting

nurse;

enrollment in smoking cessation program; oxygen

delivery; meal provisions)

Note:

A patient who does not fully meet criteria for

home discharge may be considered for discharge to a

nonacute

care facility for observation during the final

resolution of symptoms.

BACKGROUND Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is the fourth leading cause of death in the United States. Affecting 16 million people each year it accounts for 13.8 million office visits and 297,000 hospitalizations at a cost of 18 billion dollars'. Even more distressing is the fact that mortality due to heart disease and stroke have decreased substantially over the past 10 years, mortality from COPD has increased by 33%. Despite the fact that acute exacerbations of COPD account for a relatively high proportion of hospital admissions in the United States, indications for hospitalization and length of hospital stay have received very little attention. Relatively few studies have investigated patient-specific, objective clinical and laboratory features identifying patients with COPD who require hospitalization.

This led to the formulation of consensus guidelines for COPD management by various specialty organizations, the American Thoracic Society', the British Thoracic Society, the Canadian Thoracic Society, and the European Respiratory Society. A recent review3 shows that these guidelines are substantially similar in nature. This review also emphasized that these COPD guidelines are restricted by limited empirical evidence. With these considerations in mind, physicians from Kaiser Permanente Northern California convened to develop a systematic approach that would help physicians identify and treat high-risk patients needing admission among those presenting with an acute exacerbation. While we undertook an extensive literature search and critically reviewed available evidence in developing this approach we acknowledge the lack of large, double blind, placebo- controlled clinical trials addressing fundamental questions of management. It is for the aforementioned reason TMPG has entitled this document as a Clinical Practice Statement as opposed to a Clinical Practice Guideline.

REFERENCES 1. Standards for the diagnosis and care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152(5 Pt 2):S77-121. Items reprinted with permission.

2. U.S. Department of Commerce. Bureau of the Census. Statistical abstract of the United States 1997. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, November 1997.

3. Fabbri L et al. Curr Opin Pulm Med 1998;4:78-84.

4. Fuso L et al. Am J Med 1995; 98:272-7.

5. The SUPPORT investigators.AmJRespir Crit Care Med 1996;154(4 Pt l):959-67 [published erratum appears in Am J Respir Crit Car Med 1997 Jan;155(l):386].

6. Seneff MG etal./AM 19951274:1852-7.

7. MoranJL at al. Crit Care Med 1998;26:71-8.

8. Shrestha M at al. Ann Emerg Med 1991120:1206-9.

9. COMBIVENT Inhalation and Aerosol Study Group. Chest 1994;105:1411-9.

10. Levin DC et al. Am J Med 1996;100(IA):40S-48S.

11. Tashkin DP et al. Am J Med 1996;100(IA):62S-69S.

12. Kuhl DA et al. Ann Pharmacother 1994;28:1379-88.

13. Turner MO et al. Arch Intern Med 1997:157:1736-44.

14. Albert RK et al. Ann Intern Med 1980:92:753-8.

15. Murata WH et al. Chest 1990;98:845-9.

16. Thompson WH et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154(2 Pt l):407-12.

17. SCCOPE Study Group. Control Clin Trials 1998;19:404-17. Results presented at the International Conference for American Lung Association/American Thoracic Society, April 1998, will be published in an upcoming issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

18. Anthonisen NR et al. Ann Intern Med 1987:106:196-204.

19. Saint S. et al. JAMA 1995;273:957-60.

20. Rice KL et al. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:305-9.

21. Wrenn K et al. Ann intern Med 1991:115:241-7.

CONTACT INFORMATION Kaiser Pemianente Northern California TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization 1800 Hamson Street, 4th Floor, Oakland, CA 94612 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950

To obtain more information about KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines, printed copies, or permission to reproduce any portion, please contact the TPMG Dept. of Quality & Utilization, or send an e-mail message to clinical.guidelines@ncal.kaiperm.org KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines can be viewed on-line on the Kaiser Permanente Northern California intranet website at http://clinical-library.al.kp.org This website is accessible only from the Kaiser Permanente computer network.

This Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) Clinical Practice Statement has been developed to assist clinicians by providing an analytical framework for the evaluation and treatment of selected common problems encountered in patients. This statement is not intended to establish a protocol for all patients with a particular condition. While the statement provides one approach to evaluating a problem, clinical conditions may vary significantly from individual to individual. Therefore, the clinician must exercise independent judgment and make decisions based upon the situation presented.While great care has been taken to assure the accuracy of the information presented, the reader is advised that TPMG cannot be responsible for continued currency of the information, for any errors or omissions in this statement, or for any consequences arising from its use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CLINICAL LEADER David Goya, DO, MBA, FCCP, FACP, Pulmonology; Santa Clara CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE TEAM Mark Clark, MD, HBS; Vallejo Nada Ferns, NP, Medicine; Hayward PROJECT MANAGEMENT Jay Krishnaswamy, MBA, Department of Quality and Utilization (DOQU) Linda Rogers, MPA, DOQU EDITING The Medical Editing Department, Kaiser Foundation Research Institute REVIEWERS Joe Anderson, RT; Redwood City Christine Angeles, MD, Pulmonology; South San Francisco Richard Blohm, MD, Medicine; Sacramento George Bulloch, MD, Emergency; Redwood City Laura Butcher, MD, Medicine; San Jose Tony Cantelmi, MD, Medicine; Roseville Doug Chartier, MD, HBS; Oakland Uli Chettipally, MD, Emergency; South San Francisco John David, MD, Emergency; San Rafael Paul Feigenbaum, MD, Medicine; San Francisco Maurice Franco, MD, Medicine; Hayward Eric Koscove, MD, Emergency; Santa Clara Pansy Kwong, MD, Medicine; Oakland Lewis Lehman, MD, HBS; San Franrisco David Langkammer, MD, Medicine; Antioch Susan Marantz, MD, Pulmonology; Santa Rosa Tom Padgett, MD, Emergency; San Francisco Bill Plautz, MD, Emergency; South San Francisco Christina Shih, MD, Emergency; San Francisco Kurt Swartout, MD, HBS; Sacramento Christopher Tyier, MD, HBS; San Francisco Tuan Tran, MD, HBS; Stockton Abdul Wali, MD, HBS; Walnut Creek GRAPHIC DESIGN Gail Holan,Curvey Graphic Design

Copyright 1999 The Permanente Medical Group, Inc. Kaiser Diagnostic and Treatment Documents