CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE for UNSTABLE ANGINA/NON-Q-WAVE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

ENDORSED BY: CHIEFS OF CARDIOLOGY CHIEFS OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE HOSPITAL BASED SPECIALIST PEER GROUP CHIEFS OF MEDICINE

INTRODUCTION Acute Coronary Syndromes (ACS) from unstable angina to acute myocardial infarction are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. There are 6 million emergency room visits for chest pain each year in the United States with 650,000 yearly hospital admissions for unstable angina with 2% to 10% of these patients developing a myocardial infarction with a 2% to 5% 30-day mortality rate. In addition, there are 750,000 yearly admissions for acute myocardial infarction. A patient presenting with unstable angina or a non-Q-wave MI has a 10% chance of developing a Q-wave MI or dying. The six-month mortality rate of ACS patients with ST depression is 9%, for ACS patients with T wave inversion the mortality rate is 3% and for ACS patients with ST elevation treated with thrombolytics the mortality rate is 6%.

In October 1998 TPMG released an evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline for evaluating the possibility of ACS in patients presenting with chest pain and a guideline for the treatment and management of patients with an Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI). TPMG clinicians and other health care professionals are strongly encouraged to review these Clinical Practice Guidelines as they provide extensive recommendations on evaluating and managing these patients.

The purpose of this guideline is to address treatment strategies in the present era of new therapies and serum cardiac markers for patients with definite or confirmed ACS without ST elevation, who therefore are possibly at high or intermediate short term risk for AMI or death. This Unstable Angina/Non-Q-Wave MI Clinical Practice Guideline bridges the gap that currently exists between the Chest Pain and AMI guidelines presently in use.

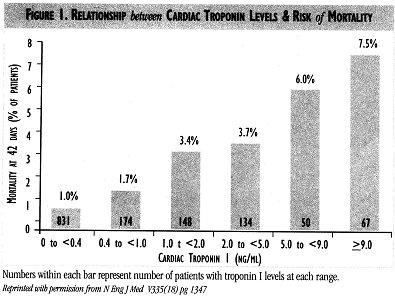

Numbers within each bar represent number of patients with troponin I levels at each range. Reprinted'with permission from N Eng J Med V335(8) pg 1347

UNSTABLE ANGINA/NON-Q-WAVE MI: INITIAL EVALUATION & PATHWAY * For initial evaluation of patients with possible ACS, clinicians should refer to Clinical Practice Guidelines for Evaluating Acute Coronary Syndrome in Chest Pain Patients in the Emergency Department, published by TPMG.

*ACS patients with ST elevation of 0.lmv (1 mm if ECG done at standard scale of lmV= 10 mm) or greater in 2 or more contiguous leads and in cases of suspected MI and left bundle branch block are candidates for reperfusion therapy (thrombolytics or primary PTCA). Clinicians should refer to Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Myocardial Infarction published by TPMG for managing these patients.

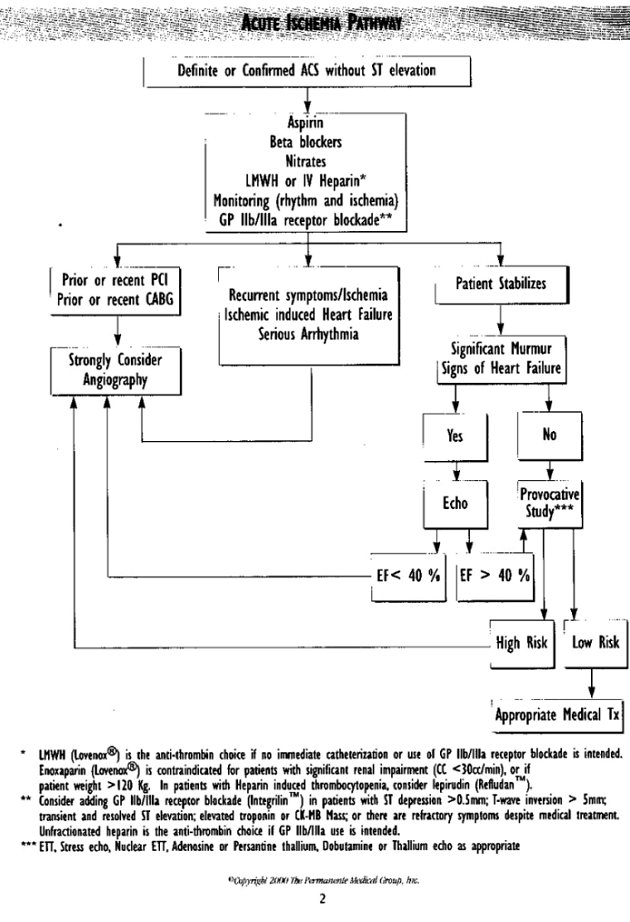

*Patients with definite ACS based on clinical presentation or ACS confirmed by dynamic ST segment shifts, deep T-wave inversions, ST depression, hemodynamic abnormalities or positive cardiac markers should be treated according to the Acute Ischemia Pathway.

SERUM CARDIAC MARKERS Serum cardiac markers, particularly creatine kinase (CK), have long been used as indicators of myocardial necrosis. Serum CK-MB Mass has improved sensitivity for the diagnosis of MI within the first 6 hours. Cardiac-specific troponins, troponin-T and troponin-I, are macromolecules that are not detected in the blood of healthy individuals, and thus offer improved specificity for the detection of myocardial necrosis. A substantial proportion of patients with ACS but no myocardial infarction based on normal serial CK-MB Mass have elevated troponins indicating focal myocyte necrosis. An elevated troponin level has been shown to have additional prognostic significance beyond that supplied by such other means as the clinical characteristics of the patient, the ECG, and a pre-discharge exercise test. In particular, elevated troponin-I and troponin-T levels identify patients at increased risk of death. Furthermore, there is a quantitative relationship between the level of elevation and the risk of mortality in those patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome (Fig. 1). However, clinical experience around KP Northern California has documented the presence of normal coronary arteries in some patients despite the presence of elevated troponins. Current data suggests presence of renal failure, myopericarditis, or cardiomyopathy may cause false positive troponin elevations.

Measurement

of both troponin I and CK-MB Mass provide

complementaiy information in the evaluation of intermediate and high

risk

patients with

possible ACS. Troponins also are clearly helpful

in patients presenting more than 24 hours after onset of symptoms as

they

remain elevated

while

CK-MB levels may have normalized. Also ACS patients

without ST elevation and an elevated troponin exhibit a greater benefit

from newer antiplatelet

or antithrombotic therapies, such as platelet

glycoprotein llb/llla inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin. Thus,

in patients with

definite or confirmed ACS a single troponin

I measurement should be strongly considered (in conjunction with CK-MB

Mass) in the Emergency Department and another measurement repeated 8-12

hours after admission. The guideline team highly recommends facilities

that currently do not have troponin I processing capabilities work

toward

making it available as troponin I offers the clinician added prognostic

value for the management of the patient with ACS.

Given the time

frames of the release of serum cardiac markers, it is important that

clinicians

consider the time of onset of symptoms when interpreting the results of

serum cardiac marker measurements. The diagnostic accuracy can be

improved

by obtaining serial measurements over several hours. (See the Chest

Pain

Guidelines for recommendations of a diagnostic strategy for use in

chest

pain observation units.)

Measurement

of both troponin I and CK-MB Mass provide

complementaiy information in the evaluation of intermediate and high

risk

patients with

possible ACS. Troponins also are clearly helpful

in patients presenting more than 24 hours after onset of symptoms as

they

remain elevated

while

CK-MB levels may have normalized. Also ACS patients

without ST elevation and an elevated troponin exhibit a greater benefit

from newer antiplatelet

or antithrombotic therapies, such as platelet

glycoprotein llb/llla inhibitors and low molecular weight heparin. Thus,

in patients with

definite or confirmed ACS a single troponin

I measurement should be strongly considered (in conjunction with CK-MB

Mass) in the Emergency Department and another measurement repeated 8-12

hours after admission. The guideline team highly recommends facilities

that currently do not have troponin I processing capabilities work

toward

making it available as troponin I offers the clinician added prognostic

value for the management of the patient with ACS.

Given the time

frames of the release of serum cardiac markers, it is important that

clinicians

consider the time of onset of symptoms when interpreting the results of

serum cardiac marker measurements. The diagnostic accuracy can be

improved

by obtaining serial measurements over several hours. (See the Chest

Pain

Guidelines for recommendations of a diagnostic strategy for use in

chest

pain observation units.)

Unstable Angina/Non-Q-Wave MI:Hospital Course Health Care Access

Patients suspected of having ACS should be triaged to a designated cardiac care level Emergency Room, observation unit, Transitional Care Unit/Step Down Unit, or Critical Care Unit bed with continuous monitoring of the ECG, oximetry, and non-invasive blood pressure. The initial evaluation of patients with ACS must exclude patients with pain due to active peptic disease, pulmonary embolus, and aortic dissection for which some of the following therapies are contraindicated and potentially life-threatening.

Oxygen

Pulse oximetry or an arterial blood gas (ABG) should be used for assessment of systemic oxygenation and supplemental oxygen prescribed if indicated.

Nitrates

Sublinglual, topical, oral spray, or intravenous nitrates are indicated for initial management of ischemic cardiac pain in ACS for all patients if the systolic blood pressure is over 90mm Hg. Patients should be asked about recent sildenafil (Viagra‘) use as the combination of ildenafil and organic nitrates (nitroglycerin and nitroprusside products) can lead to severe and prolonged hypotension. It appears that patients will remain at risk for a serious drug interaction for 24-72 hours after administration of sildenafil (Viagra‘), depending upon patient age, and renal and liver function. Careful attention to the use of nitrates with inferior and right ventricular infarction patients is required due to the possibility of decreasing preload and causing severe hypotension.

Analgesics

If the response to oxygen and nitrates is inadequate, administration of intravenous morphine sulfate, meperidine, or fentanyl should be considered early in adequate doses to relieve pain, to reduce stress and hypertension, and to reduce the high circulating catecholamines in response to the pain from ACS. The drug dose requirements may vary widely depending on the severity of the patient's acute pain.

Anti-platelet therapy

Antiplatelet agents are indicated in all patients with ACS who are without contraindications to anti-platelet therapy, which may include known hypersensitivity to the drugs below, active gastrointestinal or other bleeding, or known severe hemorrhagic diathesis. These drugs should be administered expeditiously.

*Aspirin (soluble 162 mg - 325 mg PO daily) is the antiplatelet agent of choice for all patients with ACS. Enteric coated products should not be used for the initial dose in order to achieve rapid biologic effects.

*Clopidogrel (Plavix‚): In aspirin allergic patients use clopidogrel 75 mg PO daily (375 mg PO loading dose may used). A loading dose achieves more rapid biologic activity against platelets. Ticlopidine (Ticlid‚) use is discouraged due to its rare but life threatening adverse side effects, including granulocytopenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura (TTP).

*Aspirin and clopidogrel may be prescribed together in patients being considered for urgent catheterization and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI). Pretreatment with aspirin (soluble 162-325 mg PO) and clopidogrel (375 mg PO loading dose and 75 mg PO clopidogrel daily or 75 mg PO clopidogrel daily without loading dose) reduces complications of the PCI procedure. Clopidogrel may increase the risk of bleeding with subsequent coronary bypass surgery (CABG) and the advantages and disadvantages of antiplatelet drug therapy should be carefully considered based on the clinical information available and the probability of requiring urgent CABG.

Beta-blockers

Beta-blocker therapy is indicated in all patients with ACS with the exception of patients with decompensated severe heart failure, cardiogenic shock, severe reactive airway disease, or significant bradycardia (heart rates less than 50 bpm). Beta- blockers reduce subsequent risk of death, myocardial infarction, emergency catheterization, and requirements for revascularization in all patients with ACS. There are several options for drug administration:

* IV atenolol (Tenormin) 5 mg IV repeated by another 5 mg IV in 10 minutes, and followed by 25-100 mg PO daily or

*a IV metoprolol (Lopressor) 2-5 mg doses every 5 minutes to 15 mg total dose, and followed by 25-100 mg PO 2 x day or

*Oral therapy: In lower acuity situations for patients with ACS oral initiation of therapy with beta-blockers is appropriate. Atenolol 25-100 mg PO daily is recommended or metoprolol 25-100 mg PO BID or

*Severe instability: IV esmolol loading dose and infusion may be considered with severe clinical instability. IV esmolol is an ultra short acting beta-blocker that requires a loading dose and constant infusion, which must be titrated to the desired clinical effect. Esmolol therapy generally begins with a 500 microgram/kilogram bolus over 1 minute followed by a constant infusion of 50 micrograms/kilograms/minute for 4 minutes. If a satisfactory response is not obtained, the bolus is repeated before each sequential step-up in infusion rate through 100, 150, and 200 micrograms/kilograms/minute . Patients on stable outpatient regimens of beta-blockers should continue their outpatient drug and dose if there are no contraindications.

Anti-thrombin therapy to be in addition to aspirin or clopidogrel

Antithrombin therapy (Unfractionated Heparin or Low Molecular Weight Heparin) is to be used in addition to aspirin or clopidogrel in all eligible ACS patients. Contraindications to anti-thrombin therapy include active clinical bleeding, recent surgery, recent stroke, acute head injuries as part of a complication of ACS (syncope), and proliferative diabetic retinopathy with hemorrhage. Heparin therapy is generally continued for 24-48 hours or until stabilization, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), or CABG. Patients already anticoagulated with warfarin (Coumadin‚) need special attention. The warfarin is usually discontinued and either unfractionated heparin or enoxaparin (Lovenox‚) is substituted. Patients with known hypersensitivity to heparin (heparin induced thrombocytopenia) should be considered for therapy with lepirudin rDNA (Refludan‘).

Low Molecular Weight

If no immediate catheterization or use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade is intended, LMWH is the anti-thrombin choice for patients with ACS. Safety and efficacy trials for the combination of LMWH and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade are ongoing. Currently there are inadequate data to promote their combined use. Enoxaparin (Lovenox‚) should be administered as lmg/kg subcutaneously every 12 hours. If premixed syringes are used, doses can be rounded to the nearest syringe size based on the patients body weight in Kg (40,60,80, and 100 mg). Enoxaparin has been shown to have a favorable ratio of antifactor Xa: antifactor II activity compared to other LMWH products currently available. TIMI II B and the ESSENCE trials provide the evidence that early weight adjusted enoxaparin will not only reduce death and MI but also the need for revascularization in suitable selected patients (duration of therapy in these trials ranged from 2 to 8 days). While it appears that the risks of major hemorrhage are approximately the same as unfractionated heparin, the risks of minor hemorrhage is slightly increased with enoxaparin. The therapeutic benefits supporting the introduction of enoxaparin in ACS clearly outweigh the increased risk of minor hemorrhages.

Enoxaparin is easier to administer than unfractionated heparin and requires no PTT monitoring and can achieve therapeutic anti-thrombin levels within 30 minutes of administration. Enoxaparin should be discontinued 4-6 hours prior to scheduled catheterization or 12 hours prior to scheduled CABG.

For patients with significant renal impairment (e.g. creatinine clearance < 30cc/min), factor Xa levels should be monitored to adjust the dosing of enoxaparin. Since this is not practical unfractionated heparin is the agent of choice in these patients. Enoxaparin also should not be used for patients with body weight > 120 Kg due to a lack of dosing guidelines.

Most patients with ACS will become clinically stable with medications and will not require emergency catheterization. When catheterization is scheduled, the last dose of LMWH should be 4-6 hours prior to the procedure. During catheterization careful attention should be paid to the timing of the last dose of LMWH, since the aPTT and activated clotting times (ACT) will not reflect LMWH heparin anti-factor Xa activity. If LMWH was given within 8 hours of cardiac catheterization, a vascular closure device is recommended or one should wait 8 hours following the last LMWH dose to remove vascular sheaths. LMWH can be restarted 2 hours after vascular closure, if clinically appropriate. No adjustment to vascular access management is required if catheterization is performed after 8 hours from last enoxaparin injection. If PCI is performed and LMWH was given 6-8 hours prior to PCI, then 2,000 units of unfractionated heparin should be given with a lower targeted ACT of 150-200 sec. For detailed information on enoxaparin, refer to the P&T formulary section of the National Pharmacy intranet site at http:\\pharmacy.kp.org or contact KP Drug information at 8-345-2340.

Unfractioned heparin

If immediate catheterization or use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade is intended, unfractionated heparin is the anti-thrombin choice for patients with ACS. Unfractionated heparin is also the agent of choice for ACS patients with significant renal impairment (e.g. creatinine clearance < 30cc/min), and for patients with body weight >120 kg. Unfractionated heparin may be used with an intravenous loading doses and maintenance infusions with a therapeutic goal of an activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) 1.5-2.0 x control. Monitoring is required for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). One should consider lepirudin rDNA (Refludan‘) use for ACS and CABG patients requiring anti-thrombin therapy with prior HIT.

If use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade is intended unfractionated heparin with a modified loading dose and infusion should be considered. There are a number of heparin dosing regimens for unfractionated heparin and there is no consensus on the best regimen, although reduced doses are required when used in conjunction with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade to minimize bleeding complications:

*Weight adjusted heparin dose: Heparin bolus of 60 U/kg followed by 12 U/kg/hour for 48-72hrs (with a maximum of 4000 U bolus and l000U/h infusion for patients weighing > 70 Kg). Weight adjusted heparin dosing is likely to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation without overshoot or undershoot of the aPTT goal (1.5 to 2.0 x control or between 50 and 70 sec). The lower end of the aPTT goal should be the objective when glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptors are used.

*Low and ultra low dose weight adjusted heparin: low dose heparin bolus of 60 U/kg IV followed by 7-12 U/kg/hr or ultra-low dose of 30 U/kg followed by 4 U/kg/hr are under investigation when used in conjunction with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade and may be considered alternatives to the weight adjusted regimen above in selected patients.

* Non weight adjusted heparin administration is not recommended.

Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GP IIb/IIIa) receptor blockade

Three drugs have been approved for use as intravenous agents for blockade of the platelet IIb/IIIa glycoprotein receptors and inhibition of platelet aggregation and activation in patients with ACS: eptifibatide (Integrilin‘, KPformulary) (PCI and ACS), tirofiban (Aggrastat‚, KP non- formulary) (ACS), and abciximab (Reopro‘) (PCI). These three drugs are quite different structurally from each other and have different indications and dosing.

Contraindications for all three agents include: Active bleeding, recent surgery, diabetic hemorrhagic retinopathy, renal failure (creatinine > 4.0 mg/dl or chronic dialysis), platelet count < 100,000, pregnancy, recent head trauma, intracranial arteriovenous malformation or tumor, pericarditis, uncontrolled severe hypertension, aortic dissection, or recent non-hemorrhagic stroke or any prior hemorrhagic stroke. In hemorrhagic emergency, or should surgery be required, all three drugs should be discontinued. Fresh platelet transfusions will reverse the antiplatelet effects of abciximab but will not reverse the antiplatelet effect of eptifibatide or tirofiban. The simple discontinuation of eptifibatide or tirofiban infusion however will lead to return of normal platelet function in 4 to 6 hours due to the short half life of these drugs. Monitoring of platelet counts along with the hematocrit is required with utilization of the GP IIIb/IIIa receptor blockade to monitor for the presence of bleeding and also for the possible risk of thrombocytopenia which occurs in 1 to 2% of patients treated with abciximab but much less with eptifibatide or tirofiban. For detailed information on eptifibatide refer to the P&T formulary section of the National Pharmacy Intranet site at http:\\pharmacy.kp.org or contact KP Drug information at 8-345-2340.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockade in ACS patients with ST depression > 0.5 mm; T-wave inversion > 5 mm; transient and resolved ST elevation; elevated troponin or CK-MB Mass; or prior diagnosis of CAD by catheterization, PCI, CABG, MI, or positive non-invasive imaging: These patients are at higher risk of MI, death, or urgent revascularization and should be considered for GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade in addition to aspirin, beta-blockers, nitrates, and heparin.

Glycoprotein llb/llla receptor blockade in ACS patients without ST elevation or depression and with normal troponin or CK-MB Mass: This is a subgroup of the ACS patients who are at lower risk for MI, death, or urgent revascularization. GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade should be considered for these lower-risk patients only when there are refractory symptoms and a prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease by catheterization, PCI, CABG, MI, ETT or positive non-invasive imaging study. Risk-benefit ratios should be considered when contemplating GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade in lower-risk patient populations. In the absence of ST segment changes great care is required to exclude aortic dissection andgastrointestinal hemorrhage/ peptic ulcer disease prior to initiation of therapy.

Eptifibatide (Integrilin‘, KP formulary) or tirofiban (Aggrastat‚, KPnon-formulury): GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade drugs have been studied in randomized ACS clinical trials. These are cyclic peptides and nonpeptides which cause reversible short acting platelet receptor IIb/ IIIa blockade for use in ACS patients according to manufacturers loading dose and infusion guidelines and continued for 48-72 hours or until discharge. Both can be continued through catheterization and PCI but must be stopped prior to CABG. Dose reductions for eptifibatide during PCI were initially recommended by the manufacturer to reduce vascular access bleeding, but there is data that insufficient platelet inhibition occurs with this dose modification and it is therefore not recommended. Dose modifications (135 mcg/kg/min over 1-2 min followed by to 0.5 mcg/kg/min continuous infusion) are required for renal impairment (creatinine 2.0 to 4.0 mg/dl). Eptifibatide is contraindicated above a creatinine of 4.0mg/dl.

* The loading dose for eptifibatide is 180 mcg/kg given IV over 1-2 minutes followed by an infusion of 2.0 mcg/kg/min for up to 72 hours or hospital discharge. The dose of the infusion may be reduced to 0.5 mcg/kg/min at the time of PCI to reduce vascular access site hemorrhage but the lower dose may not provide for adequate platelet inhibition.

*The loading dose for tirofiban is 0.4 mcg/kg/min for 30 minutes with a maintenance infusion of 0.I mcg/kg/min. The use of tirofiban is suggested only in those patients received in transfer from another medical center where therapy was initiated with tirofiban. Currently there are no safety data on conversion from tirofiban to eptifibatide therapy available.

*When patients receive eptifibatide or tirofiban are referred for catheterization and PCI, the drugs should be continued through PCI for another 12-24 hours. Careful vascular access management is required. Venous sheaths and catheters should be discouraged to reduce hemorrhagic complications.

Abciximab (Reopro‘ ): For the purposes of these guidelines abciximab is not recommended currently for the management of patients with ACS outside of the catheterization laboratory. Eptifibatide (Integrilin‘) is the preferred formulary GP llb/llla inhibitor for this indication. The role of abciximab in AMI with ST elevation is currently under investigation.

Continuum of care through catheterization and PCI

Since KP members may undergo a number of inter-facility transfers between community hospitals, KFH hospitals, and KFH or community hospitals with catheterization and PCI facilities careful consideration of the use of GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade is mandatory. Clear communication of the drug used, loading and maintenance dose infusions, and other agents must be made. There are no safety or efficacy data on using combinations of the three GP IIb/IIIa drugs during PCI. Therefore consideration should be made for continuing the initial GP IIb/IIIa therapy through catheterization and PCI according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation

*As part of the PCI/Cath/CABG pathway in centers with PCI and CABG on site: Intraaortic balloon counterpulsation is an invasive and highly effective therapy for refractory angina in the ACS patients. Experienced centers with the full range of fluoroscopic, angiographic, cardiovascular surgery, and vascular surgery support may use IABP counterpulsation for patients with refractory ACS to the above therapies. Careful case selection is required to avoid peripheral and abdominal complications.

*As part of the ACS pathway in centers without PCI and CABG on site: In CCU settings in centers without catheterization, cardiovascular surgery, and PCI facilities transfer of the patients refractory to the above ACS guidelines to a tertiary care facility should be considered. IABP is an appropriate consideration as a part of a comprehensive treatment plan for patients with ACS refractory to aspirin, oxygen, nitrates, beta-blockers, antithrombins, and GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade. Use of IABP counterpulsation requires a fully integrated team of physicians, CCU nurses, and a hospital with experienced biomedical support staff.

Thrombolytic therapy

Currently there is no evidence for efficacy or safety of thrombolytic therapy in patients with ACS without ST elevation or new LBBB. Therefore the use of thrombolytic agents (streptokinase, urokinase, tPA, rPA, reteplase, APSAC) is discouraged in patients not meeting the Acute Myocardial Infarction guidelines for thrombolytic therapy.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors

Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) can play an important role in the management of ACS patients with hypertension, or an LVEF less than 40%, or for management of congestive heart failure. They are not routinely indicated for the therapy of ACS in the absence of hypertension, CHF, or low LVEF. Angiotensin II receptor blockade, such as losartan (Cozaar‚, KP-non-formulary) maybe considered in patients for whom ACE inhibitors are indicated, but not tolerated due to cough.

Calcium channel blockade

Calcium channel blockade particularly with short acting nifedipine without beta-blockade may have adverse effects inpatients with ACS. Addition of a long acting calcium channel blockade for anti-ischemic therapy in patients on maximally tolerated doses of beta-blockers, aspirin, nitrates, heparin, and platelet IIb/IIIa receptor blockade may be considered for individual patients with ACS. The majority of benefit of calcium channel blockade has been demonstrated for patients with chronic stable angina by improvement of exercise tolerance and a decrease in angina frequency. Primary studies of calcium

channel

blockers in ACS have been disappointing. Patients

intolerant of beta-blockers or with contraindications to their use

(bradycardia,

active asthma, severe decompensated CHF) may benefit from the addition

of calcium channel blockade for therapy of the ACS:

channel

blockers in ACS have been disappointing. Patients

intolerant of beta-blockers or with contraindications to their use

(bradycardia,

active asthma, severe decompensated CHF) may benefit from the addition

of calcium channel blockade for therapy of the ACS:

*Nifedipine-long acting (Adalat‚): Short acting nifedipine should not be used in the ACS setting. Use long acting preparations with caution in patients who are not beta-blocked due to reflex tachycardia. The starting dose is 30 mg daily and may be titrated up to 90-120 mg PO daily.

*Verapamil: Use either long acting (240-480 mg PO daily) or short acting (oral doses of 80-120 mg TID-QID). Enhanced drug interactions with beta-blockers, digoxin, or amiodarone may cause profound bradycardia.

*Diltiazern: Use either long acting (120-360 mg PO daily) or short acting (oral doses of 30-90 mg QID). Enhanced drug interactions with beta-blockers, digoxin, or amiodarone may cause profound bradycardia.

*Felodipine (Plendil‚), KP non-formulary): 5-10 mg PO daily may be effective in patients with low ejection fraction.

RISK STRATIFICATION OF THE PATIENT WITH UNSTABLEhttps://kaiserpapers.com/downey/cajue/heart/ ANGINA

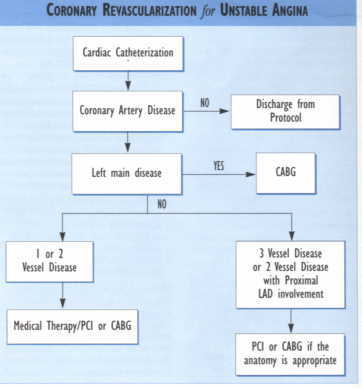

Hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome free of angina and CHF for a minimum of 24 hours should be considered for stress testing. A treadmill exercise test is appropriate for patients who can exercise without exhibiting LVH, LBBB, IVCD, digoxin effect, or ST-T wave abnormalities on the resting ECG. When ECG abnormalities are present, a thallium sestamibi stress test or stress echo should be performed. For patients unable to exercise, a persantine or adenosine thallium may be considered. With asthma or wheezing, a dobutamine or adenosine thallium-sestamibi nuclear study or dobutamine echo may be substituted. Angiography should be considered without stress testing in patients with ischemia associated with CHF, definite ECG changes such as a non-Q wave myocardial infarction or ST depression, new or worsening MR, S3 gallop, ST segment shifts or LBBB. Patients who fail to stabilize with medical treatment resulting in recurrent ischemia at low level of exercise are also candidates for angiography.ACS patients with prior revascularization with PCI within the past year or prior CABG surgery may be candidates for prompt angiography without stress

HOSPITAL DISCHARGE & DISCHARGE CARE

Long Term Medical Therapy

Please refer to the AMI guideline for specific details. Recommendations for ACS patients include: low fat diet; aspirin (ASA) 81-325 mg daily in the absence of contraindications or clopidogrel 75 mg daily if ASA allergic or intolerant; beta-blockers in the absence of contraindications; and lipid lowering agents in patients with LDL cholesterol >100. ACE Inhibitors are appropriate if patients have depressed ejection fraction (EF) < 40% with or without CHE

Discharge Instructions

Follow-up appointments should be encouraged as follows: medically treated and revascularized (PTCA/CABG) patients should be seen in 2-3 weeks and higher risk patients in 1-2 weeks. Medication instruction (to include verbal consultation with a pharmacist) to the patient and/or designated caregivers must be user friendly. Patients should be advised to discontinue any use of sildenafil (Viagra‘) until cleared by their physician.

Additionally the patient should be instructed to contact their physician if the pattern of symptoms changes (increase in frequency or severity, precipitated by less effort, or occurring at rest or during sleep) to determine the need for additional treatment. Specific instructions should be given to appropriate patients regarding smoking cessation, weight loss, daily exercise, low fat diet, hypertension control, and blood sugar regulation.

Discharge instructions should also include referral to the MULTIFIT or an alternative cardiac rehab program. The use of "Post MI Doctor's Discharge Orders" developed by the MI guideline team is strongly recommended.

SPECIAL GROUPS

Women: Women with ACS are generally older with greater comorbidities than men, have more atypical presentations, and appear to have less severe and extensive CAD. They less frequently receive aspirin and undergo angiography, but have similar use of exercise testing, and the same prognostic factors as men. Current data indicates that they should be managed in manner similar to men, although it should be recognized that the presentation may be more atypical and both stress ECG and thallium perfusion imaging are less accurate. When available stress echo can be an alternative choice. Women who have never been on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) should not be started on it during the first year post ACS.

If they are currently on HRT it may be continued. After the first year post ACS, women should be started on HRT only after discussions of personal risks and benefits.

Elderly Patients: The elderly with ACS tend to have atypical presentations of disease, substantial comorbidities, ECG tests that are more difficult to interpret, and different responses to pharmacologic agents compared to younger patients. When all cardiac and other comorbidities are considered, they can be approached in a manner similar to younger patients with attention paid to altered pharmacokinetics and sensitivity to hypotensive drugs. The indications for angiography and revascularization are similar to those in younger individuals. Overall, decisions on management should reflect considerations of general health status, patient preferences and life expectancy. Advanced directives should be reviewed and discussed.

Diabetes Mellitus: Diabetes is present in about one-fifth of ACS patients and is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes. This should be taken into account in the initial evaluation of patients with ACS. Diabetes is associated with more extensive CAD, unstable lesions, frequent comorbidities, and unfavorable long-term outcomes with coronary revascularization, especially with balloon PTCA. In caring for diabetic patients with ACS, attention should be directed toward comorbidities, including peripheral vascular disease, LV dysfunction, CHF, and autonomic neuropathy with altered anginal threshold. Patients with ACS and diabetes show a particularly strong benefit in improved outcomes with adjunctive treatment with GP IIb/IIIa receptor blockade.

Post-Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patients:Post-CABG patients who present with ACS are at higher risk with more extensive CAD and LV dysfunction than previously unoperated patients. Medical treatment should follow the same guidelines as in the non-post-CABG patients.

Repeat revascularization can be performed and is effective on the post-CABG patient, though it is more difficult technically and results in higher post-operative mortality. Due to many anatomic possibilities that might be responsible for recurrent ischemia, there should be a low threshold for angiography in patients post-CABG with ACS.

Cocaine Use: The incidence of MI in patients entering an ED with chest pain after cocaine use is very low when the initial ECG is normal or has nonspecific changes. These patients should be carefully evaluated and appropriately treated, as the use of cocaine is associated with a number of cardiac complications that can produce myocardial ischemia presenting as an ACS (e.g. coronary artery spasm, coronary thrombus, dysrhythmias, accelerated coronary atherosclerosis). NTG and calcium channel blockers are the preferred drugs in cocaine induced myocardial ischemia and vasoconstriction as both NTG and verapamil have been shown to reverse cocaine induced hypertension and coronary arterial vasoconstriction.

SELECTED ACRONYMS *ACS: Acute Coronary Syndrome *ACT: Activated Clotting Time *ASA: Aspirin *CABG: Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery * CAD: Coronary Artery Disease *CCU: Critical Care Unit *CHF: Congestive Heart Failure *CK-MB Mass: Myocardial Fraction of Creatine Kinase * ECG: 12-Lead Electrocardiogram *EF: Ejection Fraction (Left Ventricle) *ETT: Exercise Treadmill Test *GP IIb/IIIa: Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa Receptor Blockade *HRT: Hormone Replacement Therapy * IABP: Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump *IVCD: Interventricular Conduction Defect *LAD: Left Anterior Descending Coronary Artery *LBBB: Left Bundle Block Branch *LMWH: Low Molecular Weight Heparin *LV: LeftVentricular *LVH: Left Ventricluar Hypertrophy * MI: Myocardial Infarction *MR: Mitral Regurgitation * NTG: Nitroglycerine *PCI: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention * PTGA: Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty * PTT: Partial Thromboplastin Time

Selected References

1999, ACC/AHA Guidelines for Unstable Angina (currently in draft). 1999, ACC/AHA Guidelines for AMI (available online http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines). TPMG: Acute Myocardial Infarction & Chest Pain Guidelines (http://clinical-library.ca.kp.org).

TROPONINS Ohman EM, et al. Cardiac troponin T levels for risk stratification in acute myocard/httpdocs/cajud/heartial ischemia. GUSTO HA Investigators. NEngl JMed 1996;335(18):1333-134l. Antman EM, et al. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels to predict the risk of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes. NEnglJMed 1996 ;335(18):1342-9.

LMWH Cohen M, Demers C, Gurfinkel EP. A comparison of low molecular weight heparin with unfractionated heparin for unstable coronary artery disease. ESSENCE Trial. NEnglJMed 1997;337:447-452.

Antman EM et al. Enoxaparin Prevents Death and Cardiac Ischemic Events in Unstable Angina/Non-Q-Wave Myocardial Infarction Results of the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) IIB Trial Circulation. 1999;100:1593-1601.

Mark DB, Cowper PA, Berkowitz SD, et. al. Economic assessment of low-molecular-weight heparin (enoxaparin) versus unfractionated heparin in acute coronary syndrome patients: results from the ESSENCE randomized trial. Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q wave Coronary Events [unstable angina or non-Q-wave myocardial infarction]. Circulation 5-5-98;97(17):1702-1707.

Klein W, Buchwald A, Hills WS, et. al. On behalf of the FRIC investigators. Fragmin in unstable angina pectoris or in non-Q wave acute myocardial infarction (FRIC). Am J. Cardiol 1997;80(5A):30E-34E.

Swahn E,WallentinL. For the FRISC Study Group. Low-molecular-weight heparin (Fragmin) during instability in coronary artery disease (FRISC). Arn J. Cardiol 1997;80(5A):25E-29E.

GP IIb/IIIa The PURSUIT Trial Investigators. Inhibition of Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa with Eptifibatide in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Md 8-13-98;339:436-444.

The IMPACT-II Investigators. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of eptifibatide on complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: IMPACT-II. Lancet 1997;349:1422-1428.

The PRISM-PLUS Study Investigators. Inhibition of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor with tirofiban in unstable angina and non-Qwave myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998;338:l488-l489.

The PRISM Study Investigators. A comparison of aspirin plus tirofiban with aspirin plus heparin for unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1998;338:l498-1505.

The RESTORE Investigators. Effects of Platelet Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa blockade with Tirofiban on adverse cardiac events in patients with unstable angina or acute myocardial infarction undergoing coronary angioplasty. Circulation 1997;96: 1445-1453.

The CAPTURE Investigators. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of abciximab before and during coronary intervention in refractory unstable angina. Lancet 1997;349:1429-1435

The CAPTURE Study Investigators. Benefit of Abciximab in Patients with Refractory Unstable Angina in Relation to Serum Troponin T Levels, N Engl J Med 1999;340:l623-l629.

The EPIC Investigators. Use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor in high-risk coronary angioplasty. NEnglJMed 1994;330:956-96l. The EPILOG Investigators. Platelet glycoprotein llb/lla receptor blockade and low-dose heparin during percutaneous coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 1997;336:l689-1696./httpdocs/cajud/heart

The EPISTENT Investigators. Randomized placebo-controlled and balloon-angioplasty-controlled trial to assess safety of coronary stenting with use of platelet glycoprotein-IIb/IIIa blockade. Lancet 1998;352:87-92.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Clinical Leaders

Ralph Brindis, MD, MPH; Cardiology, San Francisco Eleanor Levin, MD; Cardiology, Santa Clara

Guideline Team

Sue Flynn, RN; Santa Clara Ken Linsky, Pharm.D.; Pharmacy, San Francisco Tom Padgett, MD; Emergency, San Francisco Michael Petru, MD; Cardiology, San Francisco Bill Plautz, MD; Emergency, South San Francisco

Project Management

Jay Krishnaswamy, MBA; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization

Reviewers

Nancy Batmale, RN, MS; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Roger Baxter, MD; Medicine, Oakland Mark Beck, RN, MSN; Nursing, East Bay Diane Craig, MD; HBS, Santa Clara Charlotte P. Edwards, R; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Edward Fischer, MD; Cardiology, South San Francisco Russ Granich, MD; HBS, Hayward Pansy Kwong, MD; Medicine, Oakland Keith E Palmer, MD; HBS, San. Francisco Pankaj Patel, MD; Emergency, Sacramento Philip Lee, MD; Cardiology, Santa Clara Lou Lehman, MD; HBS, San Francisco Cathlene Richmond, Pharm.D.; Drug lnformation/Professional Services John Rochat, MD; Hematology/Oncology, Santa Rosa James Scillian, MD; Pathology, Stockton Christina Shih, MD; Emergency, San Francisco Dot Snow, MPH; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Jennifer Torresen, MPH; Regional Health Education Abdul Wali, MD, HBS; Walnut Creek Cheryl Wybomy, RN, MPH; TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization

Editing & Graphic Design

Linda Bine; TPMG Communications Gail Holan; Curvey Graphic Design

CONTACT INFORMATION Kaiser Permanente Northern California TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization 1800 Harrison Street, 4th Floor Oakland, CA 94612 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950 To obtain more information about KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines, printed copies, or permission to reproduce any portion, please contact the TPMG Dept. of Quality & Utilization, or send an e-mail message to clinical guidelines@kp.org

KPNC Clinical Practice Guidelines can be viewed on-line on the Kaiser Permanente Northern California intranet at http://cl.kp.org This website is accessible only from the Kaiser Permanente computer network.

Disclaimer The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) Clinical Practice Guidelines have been developed to assist clinicians by providing an analytical framework for the evaluation and treatment of selected common problems encountered in patients. These guidelines are not intended to establish a protocol for all patients with a particular condition. While the guidelines provide one approach to evaluating a problem, clinical conditions may vary significantly from individual to individual. Therefore, the clinician must exercise independent judgment and make decisions based upon the situation presented. While great care has been taken to assure the accuracy of the information presented, the reader is advised that TPMG cannot be responsible for continued currency of the information, for any errors or omissions in this guideline, or for any consequences arising from its use.

Copyright 2000 The Permanente Medical Group, IncBACK TO KAISER PERMANENTE DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT DOCUMENTS INDEX