In

Copyright

Since

September 11, 2000

Help

for Kaiser

Permanente Patients on this public service web site.

Permission is

granted to mirror if credit to the source is given and the

material is

not offered for sale.

The Kaiser Papers is not by Kaiser but is ABOUT

Kaiser

PRIVACY

POLICY

ABOUT

US|

CONTACT

| WHY

THE KAISERPAPERS

| MCRC

|

Why

the

thistle is used as a logo on these web pages. |KPRC

Announcements|

In

Copyright

Since

September 11, 2000

Help

for Kaiser

Permanente Patients on this public service web site.

Permission is

granted to mirror if credit to the source is given and the

material is

not offered for sale.

The Kaiser Papers is not by Kaiser but is ABOUT

Kaiser

PRIVACY

POLICY

ABOUT

US|

CONTACT

| WHY

THE KAISERPAPERS

| MCRC

|

Why

the

thistle is used as a logo on these web pages. |KPRC

Announcements|

Kaiser Diagnostic and Treatment Documents

Kaiser Permanente Clinical Practice Guidelines for Acute Myocardial Infarction

KAISER PERMANENTE

The Permanente Medical Group Clinical Practice Guidelines have been developed to assist clinicians by providing an analytical framework for the evaluation and treatment of selected common problems encountered in patients. These guidelines are not intended to establish a protocol for all patents with a particular condition. While the guidelines provide one approach to evaluating a problem, clinical conditions may vary significantly from individual to individual. Therefore, the clinician must exercise independent judgment and make decisions based upon the situation presented. While great care has been taken to assure the accuracy of the information presented, the reader is advised that TPMG cannot be responsible for continued currency of the information, for any errors or omissions in this guideline, or for any consequencesarising from its use.

ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES TEAM

Clinical Leader

Edward Fischer, MD, Cardiology, South San Francisco

CPG TEAM

Adria Beaver, RN, BS, Cardiology, South Sacramento Ralph Brindis, MD, MPH, Cardiology, San Francisco Mark Cole, MD, Medicine, Pleasanton Linda Daniel, RN, Critical Care, Hayward John David, MD, Emergency, San Rafael Phillip Heller, MD, Emergency, Hayward Ernie Katsumata, PharmD, Pharmacy Operations, Oakland Ellen Killebrew; MD, Cardiology, Oakland Eleanor Levin, MD, Cardiology, Santa Clara Robert Lundstrom, MD, Cardiology, San Francisco Nancy Martin, RN, BSN, Critical Care, Santa Rosa Tom Padgett, MD, Emergency, San Francisco Cathlene Richmond, PharmD, Pharmacy Operations, Oakland Steve Rose, MD, Cardiology, South Sacramento Joe Selby, MD, MPH, Division ofResearch, Oakland

PROJECT MANAGEMENT

Dot Snow, MPH, TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Dave St.Pierre, TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization

DATA ANALYSIS

Betsy Stone, DrPH, MPH, TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization Joan Bartlett, MPH, MPP, Care Management Institute

EDITING Kaiser Foundation Research Institute Medical Editing Department Linda Bine, TPMG Communications

REVIEWERS

Elizabeth Anderson, MD, Medicine, Oakland William R. Auch, MD, Medicine, South Sacramento Sandra Barbour, MD, Medicine, Sacramento Kenneth Battaglia, MD, Cardiology, San Jose Donald Byington, MD, Emergency, San Francisco Scott J. Campbell, MD, MPH, Emergency, San Francisco Tony Cantelmi, MD, Medicine, Roseville Michael Carl, MD, Emergency, South Sacramento Uli Chettipally, MD, MPH, Emergency, San Francisco Larry Davis, PharmD, Inpatient Pharmacy Manager, San Francisco David S. Gee, MD, Cardiology, Walnut Creek Marjorie Gerbrandt, MD, Medicine, Fresno Russ Granich, MD, Medicine, Hayward John P. Gumbelevicius, MD, Pediatrics, Sacramento Sandra Halliburton, RN, CCRN, Critical Care, Sacramento Gerald Horn, MD, Cardiology, South San Francisco Eileen Kahn, RN, MS, Nursing Director, Walnut Creek Skip Ketz, MD, Emergency, Hayward Kay Ko, PharmD, Pharmacy Project Manager, Santa Clara Valerie C. Kwai-Ben, MD, Cardiology, San Jose Pansy Kwong, MD, Medicine, Oakland Eric M. Koscove, MD, Emergency, Santa Clara Henry T. Lew, MD, Cardiology, Santa Clara Jane C. Lombard, MD, Cardiology, Redwood City William J. Raskoff, MD, Cardiology, San Francisco Gary Roach, MD, Cardiac Anesthesia, San Francisco Stanley J. Nussbaum, MD, Cardiology, Santa Rosa Michael A. Petru, MD, Cardiology, San Francisco Lawrence S. Troxell, PharmD, Clinical Operations Manager, Santa Clara Roland Vallecilio, MD, Medicine, Redwood City Andrea Wagner, Emergency, San Francisco Richard Wakamiya, MD, Emergency, South Sacramento Abdul Wali, MD, Medicine, Walnut Creek Albert Wilburn, MD, Medicine, Fresno David B. Williams, MD, Medicine, Vallejo Mike Witte, MD, Coastal Health Alliance, Pt. ReyesDESIGN & PRODUCTION

Gail Holan, Curvey

Ratified by the Operations Management Group and the Quality Oversight Committee, and supported by the Chiefs of Quality

”Copyright 1998 The Permanente Medical Group. Inc. All rights reserved. Please contact TPMG Department of Quality and Utilization at 510-987-2309 or tie-line 8-427-2309 for permission to reprint any portion of this publication. For additional copies of the guidelines. Please call 510-987-2950 or tie-line 8-427-2950.

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PAGE 2 DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION PAGE 3 EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT CARE PAGE 4 THROMBOLYTIC AGENTS PAGE 6 HOSPITAL CARE PAGE 7 RISK STRATIFICATION & INDICATIONS FOR CARDIAC CATHERIZATION PAGE 10 PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY PAGE 13 SECONDARY PREVENTION PAGE 14 "TEN CLINICAL PEARLS" PAGE 16 APPENDICES PAGE 17 BIBLIOGRAPHY PAGE 27In the Northern California Kaiser Permanente system, our smaller medical centers care for about 100-150 MI patients per year, and our larger centers may take care of 450 or more heart attack victims annually.

A greater understanding of the pathophysiology of acute MI has led us into the thrombolytic era, and technological advances in cardiac surgery, the cardiac catheterization lab, and stress testing have changed the way we care for our patients.

INTRODUCTION Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the most dramatic illnesses that can afflict our patients. Approximately 900,000 people in the USA are diagnosed annually with AMI. About 125,000 die "in the field", and another 125,000 die in the hospital or during the first year. Thus, there is still about a 16% in-hospital and first year mortality from heart attack.

In the Northern California Kaiser Permanente system, our smaller medical centers care for about 100-150 MI patients per year, and our largercenters may take care of 450 or more heart attack victims annually. Two year cumulative 1995-1996 risk-adjusted AMI mortality statistics (in-hospital and 30 day death rates) for each medical center in our region were disseminated at the beginning of 1998, as part of the 1997 Quality Improvement Goals. Mortality rates were close to the targets for most medical centers, and many were lower than the goal! We hope to continue to improve the quality of care delivered with implementation of this clinical practice guideline.

There have been many advances in treatment for AMI patients. We are fortunate to practice in an era when large randomized clinical trials guide the therapies we recommend. A greater understanding of the pathophysiology of AMI has led us into the thrombolytic era, and technological advances in cardiac surgery, the cardiac catheterization lab, and stress testing have changed the way we care for our patients.

With advances in treatment have also come the greater importance of decision making -what therapies and interventions will improve outcomes for our patients? A study by our Division of Research showed that in the years of 1990-1992, 48% of our post infarction patients underwent cardiac catheterization within three months of their infarct, and 57% of these patients had revascularization procedures (bypass surgery or angioplasty). At that time, there was quite a variability in the usage of these procedures from medical center to medical center. These procedures are expensive, but highly cost-effective when used appropriately.

In the 1990s, many outside organizations are also monitoring our therapies and outcomes when it comes to MI patients. The Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) compares all hospitals in the state of California for risk adjusted 30-day mortality rates and the results are published in the newspapers. The Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) also follows use of beta blockers in appropriate patients. In 1998, HEDIS is also tracking whether or not lipid panels were obtained 2-12 months after a coronary event including AMI, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), and whether the low density lipoprotein (LDL) was successfully lowered at 12 months. Many Northern California Kaiser facilities have been participating in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI). NRMI tracks whether or not reperfusion therapy was done (thrombolytics or primary PTCA), door to needle time, use of aspirin, beta blockers, and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), as well as mortality rates and hospital length of stay. Our medical centers are compared with like medical centers across the nation via the NRMI program.

Thus, the treatment of acute MI is a key topic for a clinical practice guideline:

~ it involves a high volume of patients ~ it is a high risk area ~ it is a high cost area ~ there are many new advances in treatment and testing ~ there are several treatment options a patient and physician might follow

There must be an abnormal myocardial marker (CK-MB or troponin 1) to make and confirm the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. except in those cases where the time frame is such that the damage marker might be expected to be back to normal.

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) published an extensive management guideline for MI in November, 1996. We have borrowed freely from that excellent resource to generate this guideline for Kaiser Permanente. Please refer to the ACC/AHA guideline for details regarding treatment of complications of AMI, such as use of antiarrhythmics, pacing, and intra-aortic balloon pumping. Copies of the ACC/AHA guideline can be obtained by' calling 1-800-253-4636 or by downloading from pubauth@amhrt.org. Copies are also available in the Health Sciences Library at each facility.

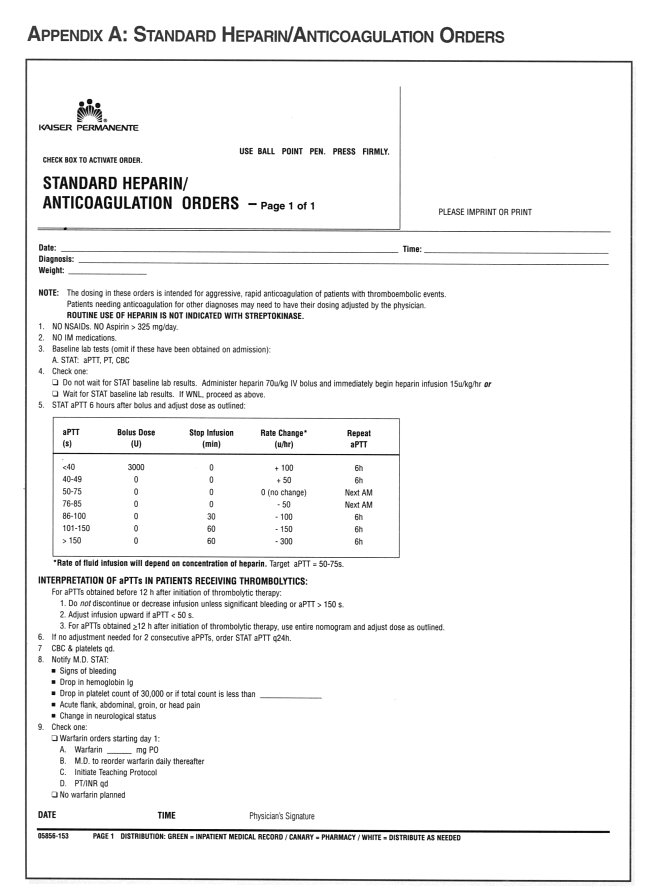

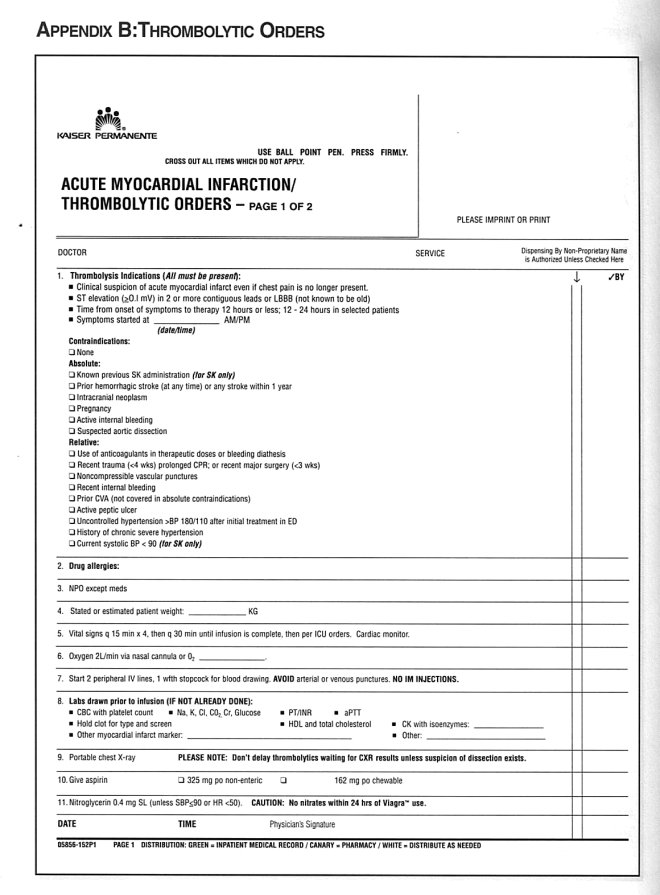

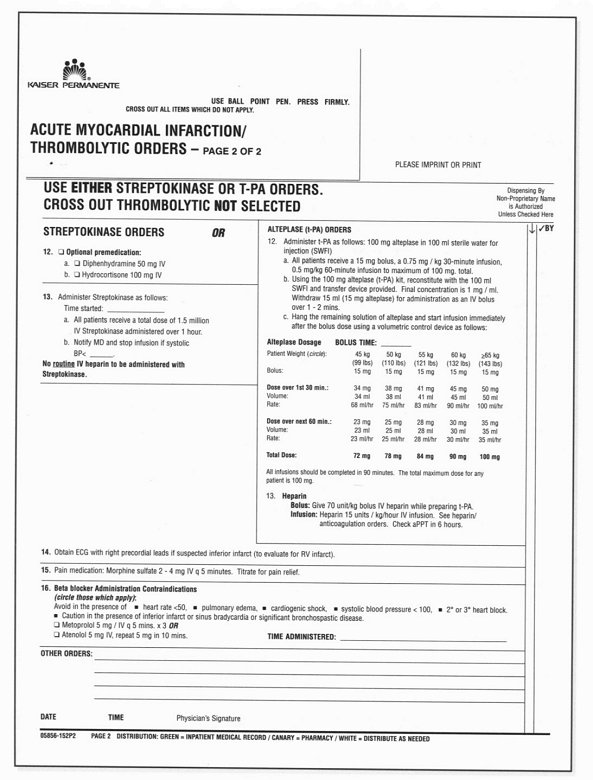

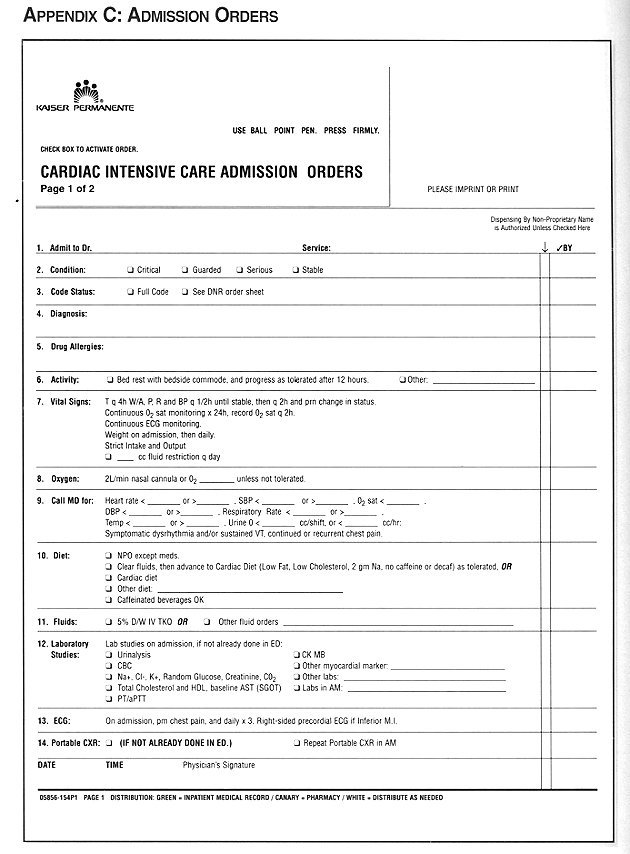

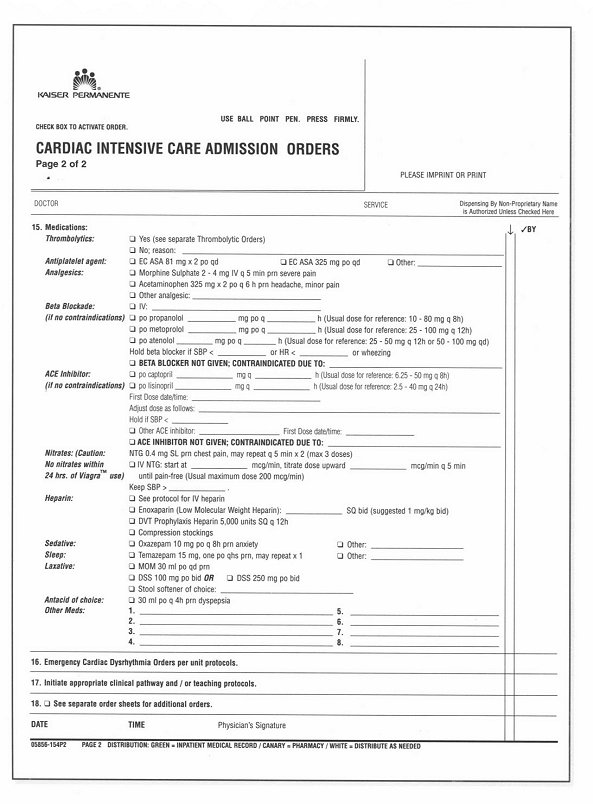

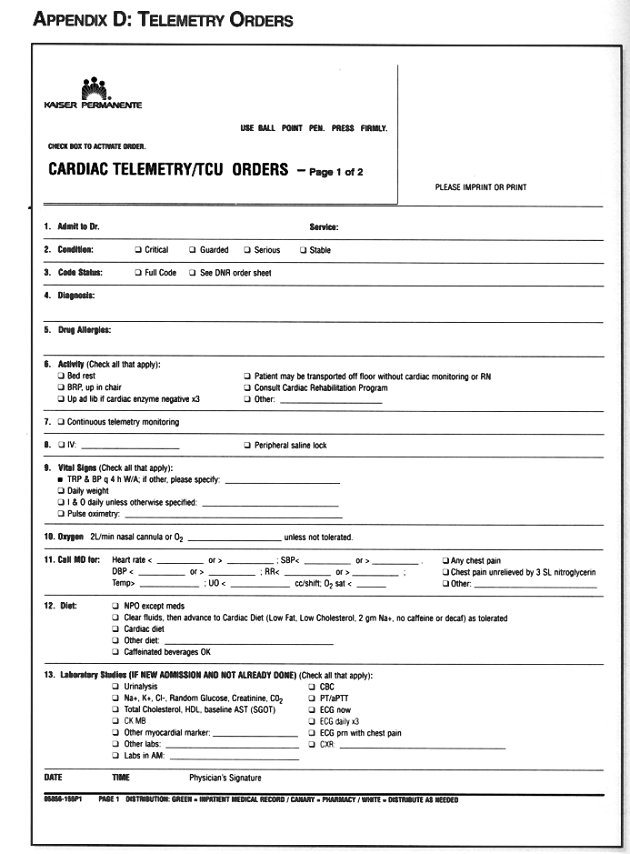

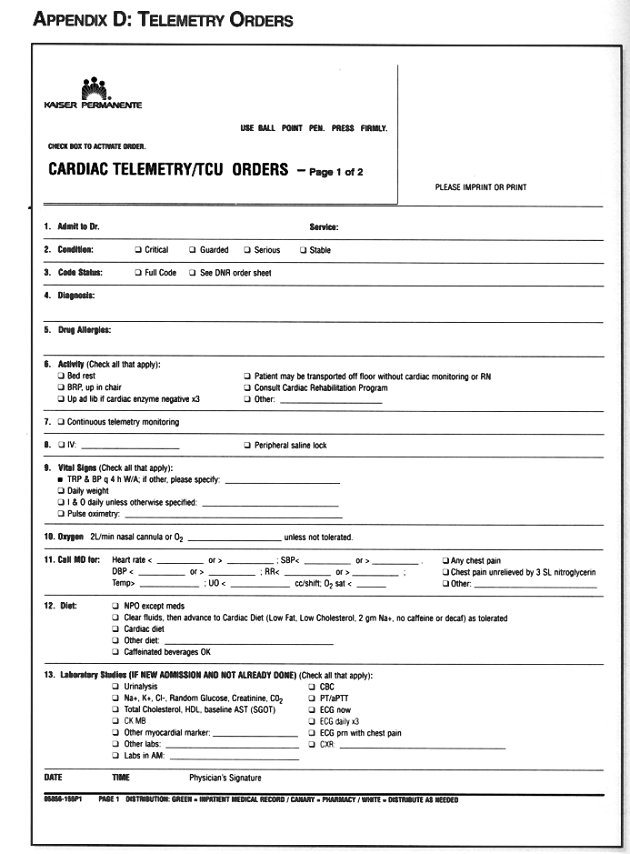

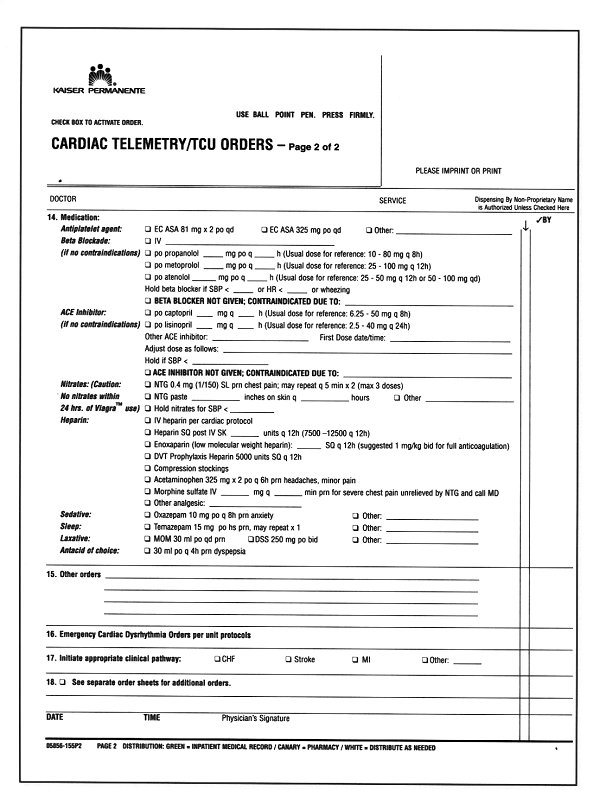

Finally, to help with the implementation of the recommendations in this guideline, the following "tools" have been created for suggested use at each facility:

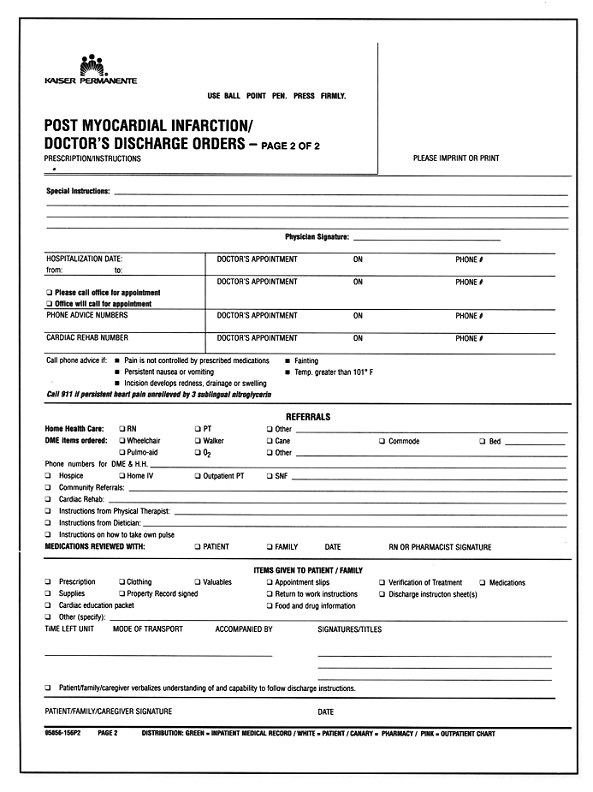

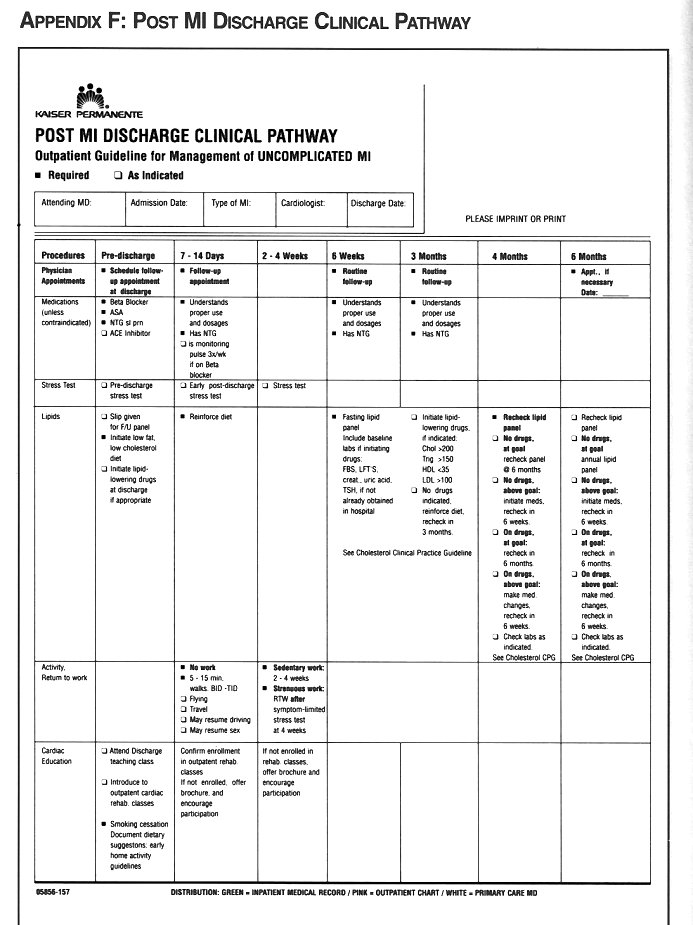

~ Standard Heparin/Anticoagulation Orders ~ Thrombolytic Orders ~ Cardiac Intensive Care Admission Orders ~ Cardiac Telemetry/Transitional Care Unit Admission Orders ~ Post Myocardial Infarction Doctor's Discharge Orders ~ Uncomplicated MI Post Discharge Clinical Care Pathway

These appear in the appendices at the end of this guideline.

DIAGNOSIS OF ACUTE MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

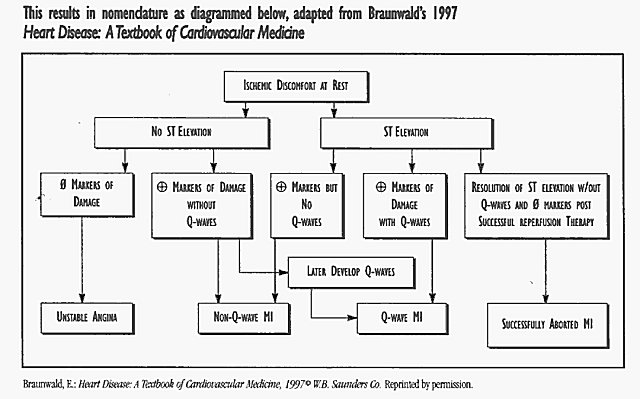

There is not a universally agreed upon definition of what constitutes an acute myocardial infarction. The World Health Organization (WHO) requires that 2 of 3 criteria must be present: a clinical history of ischemic type chest discomfort, changes on serially obtained electrocardiograms (ECGs) and a rise and fall in serum cardiac markers (such as CK-MB ortroponin I). CK-MB has been the standard biochemical marker for confirming myocardial damage, but it has several drawbacks. CK-MBis not completely specific for cardiac myocytes; the implications of slight elevations in the presence of normal total CK are uncertain; and certain clinical situations are known to cause false positive elevations (azotemia, defibrillation, myositis). Also, the interpretation of elevated CK-MB after cardiac or non-cardiac surgery can be very difficult. Troponin I is a very sensitive test for myocardial damage, but may also be mildly abnormal in cases of unstable angina or tachycardia. Confounding the situation further is the fact that there is sometimes a blurred distinction between clinical acute coronary syndromes, ranging from unstable angina to subendocardial infarction to transmural infarction.

After much review and discussion, the AMI Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) Team recommends that there must be an abnormal myocardial biochemical marker (CK-MB or troponin 1) as one of the two criteria to make and confirm the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. The exception to this recommendation would be those cases where the time frame is such that the damage marker might be expected to be back to normal (greater than 48-72 hours for CK-MB or after 5-7 days for troponin 1).

Thus, patients with ST depression or T-wave inversions who have normal biochemical markers should be diagnosed with unstable angina rather than subendocardial infarction. Furthermore, in borderline cases where there is reason to suspect a false positive elevation in CK-MB, troponin I should be done to confirm the diagnosis. Patients that present with hyperacute injury pattern on the initial ECG and then respond dramatically to therapy and have no damage marker evidence of myocardial necrosis should be diagnosed with successfully aborted acute myocardial infarction.

EMERGENCY

DEPARTMENT CARE

EMERGENCY

DEPARTMENT CARE

Many patients arrive via the 911 paramedic system. Given the complexities of diagnosis and the risks involved, there is not enough evidence at this time to recommend prehospital treatment with thrombolytics. Twelve lead electrocardiograms (ECG) faxed to the emergency department by paramedics in the field might prove to be useful at speeding therapy in the future, especially in areas where there is a significant transit time to the nearest hospital.

Once the patient with suspected MI reaches the emergency department, the evaluation, decision making, and appropriate therapy should be performed promptly. All of our emergency departments have a priority triage system that allows chest pain patients to be evaluated immediately. It is recommended that a 12 lead ECG be obtained within five minutes of the patient's arrival, and certainly no later than the nationally recommended standard of ten minutes. The goal is to deliver thrombolytic therapy, if indicated, in less than thirty minutes (door-to-needle time of less than thirty minutes). Patients presenting to clinic with suspected infarction need to be handled similarly, either by being brought immediately to the emergency department or directly to the ICU after stat ECG.

Reperfusion therapy (thrombolytics or primary PTCA) is indicated in all cases of suspected acute MI with ST elevation of 1 mv or greater in 2 or more contiguous leads and in cases of suspected MI and left bundle branch block (LBBB). Studies have shown increased morbidity without mortality reduction when thrombolytic drugs are given to patients with only ST depression and no significant ST elevation. The choice of thrombolytic agents is discussed in the next section. Although one cannot usually distinguish an acute injury or infarct pattern by ECG in patients with LBBB, there is such a high morbidity and mortality in cases of AMI complicated by new LBBB that the risk versus benefit analysis points in the direction of pursuing reperfusion for these cases. If a prior ECG can be obtained promptly and is determined to be unchanged, extra care should be taken with the clinical assessment leading to the diagnosis of AMI. Strong consideration should be given to obtaining an immediate cardiology opinion in these situations. Immediate echocardiography is sometimes useful in confirming the presence of a sizable wall motion abnormality.

All patients presenting nitb chest pain should be asked about recent sildenafil (Viagra‘) use as the combination sildenafil and organic nitrates can lead to severe and prolonged hypotension.

It is important to realize that thrombolytic therapy has a strong beneficial effect and should not be withheld for minor contraindications. Elderly patients have higher mortality rates from myocardial infarction and thus have more to gain from thrombolytic therapy, therefore advanced age is not a reason for withholding this treatment. Even if there is initial pain relief with nitroglycerin or narcotics, if ST-elevation persists, reperfusion therapy should almost always be given. Computerized ECG interpretations should be used with caution, as they often under and over diagnose acute infarction. If there is any significant doubt about diagnosis or what therapy should be pursued, immediate involvement of the cardiologist (either in person or via telephone) is recommended.

All patients presenting with chest pain should be asked about recent sildenafil (Viagra™) use as the combination of sildenafil and organic nitrates (nitroglycerin and nitroprusside products) can lead to severe and prolonged hypotension. It appears that patients will remain at risk for a serious drug interaction after administration of sildenafil for 24 - 72 hours, dependent upon patient age,renal and liver function

The initial treatment of AMI patients begins with oxygen, intravenous access, sublingual nitroglycerin (as long as systolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mmHg and heart rate is greater than 50 bpm and less than 100 bpm), 162 to 325 mg of aspirin (chewable preferred, not enteric coated), and intravenous morphine. Caution should be exercised when using nitroglycerin and/or morphine in patients with suspected right ventricular infarction, as these medications may precipitate hypotension.

Simultaneously, the physician should be obtaining the pertinent history and be performing a targeted physical exam to determine appropriateness for other therapies. If thrombolytic therapy is indicated and chosen, it should be started in the emergency department, as there is always a delay associated with moving patients. Emergency department physicians should be comfortable initiating appropriate therapy to minimize delays. Faxing of ECGs and prompt discussion with the cardiologist on call is often helpful in less obvious cases or when primary PTCA might be preferable. The indications for primary PTCA and cardiac catheterization in general are discussed in the Risk Stratification section of this guideline.

Intravenous beta blockade should be started in the emergency department, unless there are significant contraindications (heart rate <50, hypotension less than 100 mmHg systolic, active wheezing or history of significant bronchospastic disease, or presence of significant congestive failure). Caution should be exercised in patients with inferior myocardial infarction who may be more likely to develop bradycardia or hypotension. Intravenous metoprolol 5 mg every 5 minutes for three total doses is usually used, but intravenous atenolol or esmolol may be given instead. Intravenous nitroglycerin may be started in the emergency department, or upon arrival in the ICU/CCU.

The effectiveness of the "newer" reperfusion therapies for MI (thrombolysis and primary PTCA), and even the effectiveness of medical therapies like aspirin, beta blockers and ACE inhibitors are time dependent. Efforts need to be made to educate patients at increased risk of MI to present as soon as possible to our emergency departments when they have symptoms compatible with acute infarction. Appropriate high risk populations for targeted education include: patients with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes; smokers; geriatric populations; and patients with known coronary disease. Thus, the entire health care team— paramedics, Emergency Department nurses and physicians, internists or hospitalists on call, and cardiologists have a responsibility for educating the public and for promptly providing initial care for the MI patient.

The goal in the emergency department is to deliver tbrombolytic therapy in less than thirty minutes from the patients arrival. It is important to realize that tbrombolytic therapy has a strong beneficial effect in decreasing mortality and should not be withheld for minor contraindications.

THROMBOLYTIC AGENTS

Although there has been a great deal of research and debate concerning which thrombolytic drug is most effective, the most critical factor influencing outcome is symptom-to-treatment time. A great deal of emphasis should therefore be placed on having our patients present early, and then minimizing "door-to-needle" time for whichever agent is used. If thrombolytics are given within 60-120 minutes of onset of chest pain, the mortality reduction approaches 50%, as compared to an overall reduction in mortality of 18% for patients treated with thrombolytic therapy over a broader time frame. In contrast, the survival benefit imparted by thrombolytics to the late presenting patient (greater than 6 hours after onset of symptoms) is modest. The recommended door-to-needle time is therefore targeted at 30 minutes or less.

As discussed above, thrombolytic therapy is most helpful when delivered early after symptom onset; however, clinical benefit can still be achieved when thrombolytics are administered within 12 hours. In selected cases judged to have ongoing ischemic chest pain, thrombolytic therapy should also be considered up to 24 hours from onset of infarction symptoms.

At present there are four thrombolytics available for systemic intravenous treatment of AMI, two of which, TPA (Activaseģ) and streptokinase, are available on the TPMG Regional Drug Formulary. Streptokinase is an enzyme which converts plasminogen to plasmin leading to prolonged fibrinogen depletion and fibrinolysis. It is given as a 1.5 million unit constant infusion over one hour.

The major advantage of streptokinase is its low cost. The major drawbacks of streptokinase are the development of hypotension during infusion and a significant incidence of major allergic reactions. Premedication with antihistamines and steroid intravenously is often used to try to diminish this.

TPA is a more "clot specific" plasminogen activator which causes transient systemic fibrinogen depletion, is non-antigenic, but is expensive. Other thrombolytics, which are approved for treatment of AMI but offer no particular advantage and are therefore not on the formulary, are anistreplase (aka anisoylated plasminogen streptokinase activator complex-"APSAC" or Eminase‚) and reteplase (Retavase‘).

Although the symptom-to-treatment time is more critical, the choice of thrombolytic drug is of interest as we all strive to practice highest quality cost-effective medicine. "Cost-effectiveness" does not translate to "cheapest", but is a function of added benefit derived per added incremental expense. The major randomized study comparing effectiveness of streptokinase versus TPA was the Global Utilization of Streptokinase versus TPA trial (GUSTO 1) published in 1993. This study was a large, 40,000 patient international trial. Subset analysis showed that achieving brisk bloodflow down the infarct related artery (TIMI III flow) at 90 minutes post treatment was a key predictor of mortality. With good flow, mortality was 5%, but with less brisk flow mortality was twice that at 10%. Furthermore, the Thrombolysis in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial III along with the angiographic subset of GUSTO I showed that this brisk flow at 90 minutes post treatment occured only 30% of the time with streptokinase, but 50% of the time post TPA. The results of GUSTO I showed that TPA did reduce MI mortality slightly more than streptokinase, and that using TPA (rather than streptokinase) saved one extra life per 100 treated patients.

The AMI CPG Team recommends using an estimation of the amount of myocardium still at risk to help choose between SK and TPA. This strategy uses the ECG, a bedside assessment of hemodynamic stability, and the time of onset of symptoms to help increase the "cost-effectiveness" of TPA by using it in the patient population most likely to show survival benefit.

TPA is recommended for patients with: ~ Anterior MI ~ Large inferior MI (any lateral or posterior involvement, any anterior ST depression, suspected RV involvement, any hemodynamic compromise or heart block) ~ Prior streptokinase administration, or recent strop mfection, or hypotension

Streptokinase should be equally effective for patients with: ~ Small inferior MI ~ Late presentations, greater than 6 hours after symptom onset

HOSPITAL CARE

All patients with acute infarction requiring reperfusion therapy should be admitted to the ICU/CCU. Our own Kaiser statistics show that about 50% of infarction patients do not have obvious ST elevation upon presentation, and the diagnosis is made later in the hospital course by virtue of abnormal myocardial damage markers, such as CK-MB or troponin I, and/or by review of ECGs.

These patients can be considered for thrombolytic therapy if subsequent ECGs show ST elevation and there is ongoing ischemic pain. Patients who are "ruling in" for MI who were not initially admitted to the ICU/CCU should be transferred if there is ongoing chest pain, thrombolytics are being instituted, there is hemodynamic instability, or if there are any significant arrhythmias or conduction abnormalities. Otherwise, depending upon the staffing and protocols of our various telemetry units, patients who "rule in" for these usually smaller types of infarctions who are painfree and stable may stay in the telemetry unit and receive low dose intravenous nitroglycerin or topical nitrates as well as other standard therapy.

Thrombolytic therapy recipients and other patients with large or obvious infarctions should spend the first 24-48 hours of hospitalization in the ICU/CCU. It is recommended that in hemodynamically stable pain-free patients bedrest with bedside commode privileges be in effect for the first 12 hours. They should be monitored by ECG telemetry, preferably in a lead that shows both the p wave (if in sinus rhythm) and the ST elevation. Pulse oxymetry is routine for at least 24 hours or as long as the patient is in the ICU/CCU. There is evidence to favor supplemental oxygen in all patients for only the first several hours, but it is routinely used for the first 24 hours. Oxygen may be stopped after 6 hours in uncomplicated patients if desired.

Intravenous beta blockers should be given to all patients without contraindications. If not already given in the emergency department, it should be administered as soon as possible in the ICU/CCU. Oral maintenance beta blockade should be then started so that the effects overlap. Beta blockers have been proven to reduce morbidity and mortality in the initial hours of evolving MI, and also the weeks, months, and year after MI (secondary prevention). Beta blockers have a direct ventricular anti-arrhthymic effect which plays a major role in their effectiveness at reducing mortality. They also exert a beneficial effect by reducing myocardial oxygen demand via reductions in heart rate, blood pressure, and contractility. The rate slowing effect prolongs diastole, allowing for augmentation ofperfusion to injured heart muscle, especially the subendocardium which is dependent on diastolic coronary flow. Immediate treatment with beta blockers has been proven beneficial whether or not thrombolytics are given.

Reperfusion therapy (thrombolytics or primary PTCA) is indicated in all cases qf suspected AMI with ST elevation of 1 mv or greater in 2 or more contiguous leads and in cases of suspected AMI and left bundle branch block (LBBB).

Studies have shown increased morbidity without mortality reduction when thrombolytic drugs are given to patients with only ST depression and no significant ST elevation.

Soluble aspirin should have been given immediately on presentation, and should be continued on a daily basis indefinitely. Aspirin prevents formation of thromboxane A2 in platelets, a substance that induces aggregation. Cyclooxygenase inhibition lastsfor the life of the cell, or approximately 10 days. Doses as low as 75 mg a day are effective, but initially a dose of at least 162 mg to 325 mg of soluable aspirin should be given, and the AMI CPG Team is recommending 162 mg to 325 mg per day of aspirin indefinitely in almost all nonallergic patients. If the patient has serious upper gastrointestinal intolerance to aspirin, consider rectal aspirin suppositories. If there is true aspirin allergy, strongly consider the use of other anti-platelet agents such as clopidogrel or ticlodipine. Clopidogrel was released in May of 1998, and is given as a single 75 mg daily oral dose. Based on a study of 10,000 patients who received the drug for I to 3 years, it appears to be safe and does not have the significant incidence of severe neutropenia that is associated with ticlodipine (0.8% severe neutropenia with ticlodipine).

Ticlodipine has also recently been recognized to cause thrombocytopenic purpura. Both ticlodipine and clopidogrel inhibit the binding of ADP to its receptor on platelets, thereby inhibiting ADP-dependent activation of the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa complex, which is the major receptor for fibrinogen on the platelet surface. The full anti-platelet effects of these agents are delayed until 24 to 72 hours after starting.

Intravenous nitroglycerin should be used in all patients with large infarctions, anterior infarction, AMI with CHF, persistent ischemia, or hypertension, even in pain-free patients, for at least the first 24-48 hours of hospitalization, as long as systolic blood pressure is greater than 90 mmHg. Exceptions would include patients with sildenafil (Viagra‘) use. Patients with small, uncomplicated myocardial infarctions are often treated with topical or oral long-acting nitrates. Nitroglycerin induces relaxation of vascular smooth muscle in veins, arteries and arterioles, resulting in a preload reducing effect on both the left ventricle and right ventricle, an afterload reducing effect on the left ventricle, and a direct vasodilation of the coronary arteries. It can also increase coronary collateral flow and prevent coronary vasoconstriction. Intravenous nitroglycerin is usually used in doses of l0mcg/min up to 200mcg/min. Intravenous nitroglycerin is started as a drip of 10 to 20 micrograms per minute with the dose increased by about 10 micrograms every 5 to 10 minutes. Usual end points are control of pain or decrease of mean blood pressure by 10% (or 30% for patients with hypertension).

Intravenous nitroglycerin should be held or decreased if systolic pressure is less than 90 mmHg, or if heart rate exceeds 110 bpm.

Intravenous heparin is not recommended routinely after streptokinase or other non selective tbrombol\tics.

Aspirin should be given immediately upon presentation and should be continued on a daily basis indefinitely unless tbe patient is truly allergic.

Routine use of intravenous-lidocaine is not recommended.

Heparin is recommended (as a weight-based bolus and infusion) for patients post TPA for 48 hours, with a goal of an aPTT of 1.5 to 2 times control, or about 50 to 75 seconds). Heparin is no longer routinely recommended as an intravenous infusion immediately after streptokinase or other nonselective thrombolytics. If intravenous heparin is to be used post streptokinase, such as in a patient with atrial fibrillation, then an aPTT should be checked four hours post streptokinase. In this circumstance the heparin should be started without a bolus when the aPTT has returned to the therapeutic range. Heparin should be continued longer than 48 hours post thrombolytics in patients felt to be at high risk for deep venous thrombosis or systemic embolism (i.e. large anterior MIs, atrial fibrillation). These latter patients should be considered for warfarin, subcutaneous heparin, or aspirin alone, depending on the recommendations of the consulting cardiologist. Some cardiologists favor the use of 7,500 to 12,500 units of heparin every 12 hours given subcutaneously in patients post streptokinase, until they are fully ambulatory. Intravenous heparin is also recommended if there is recurrent chest pain or if the patient is felt to be high risk for reocclusion. The evidence favoring the use of intravenous heparin in acute MI patients who were not treated with thrombolytics is limited, but many of these patients will have been admitted with a diagnosis of unstable angina and most of these patients will be treated with heparin or low molecular weight heparins anyway.

There have been a number of large randomized clinical trials evaluating the use of ACE inhibitors early in AMI. Although one study from Scandinavia (CONSENSUS) using intravenous enalaprilat showed increased mortality in the treated group, all of the studies assessing early use of oral ACE inhibitors have shown survival benefits (ISIS-4 and GISSI-3). The greatest benefits were seen in the patients with anterior MI, prior MI, CHF, tachycardia, or other evidence for a large amount of nonfunctioning myocardium. The studies showed benefit when the drugs are started early (within the first 24 hours of infarction) but they should generally be started after thrombolytic therapy has been completed and the blood pressure has been stabilized. Some cardiologists favor starting ACE inhibitors early in all MI patients, and then stopping them at six weeks post infarction in those without CHF or significant LV dysfunction. Other cardiologists recommend using ACE inhibitors in the larger infarcts only (anterior infarcts, clinical CHF, tachycardia, or sizable wall motion abnormalities). ACE inhibitors are contraindicated if systolic blood pressure is below 100, if there is clinically relevant azotemia, if bilateral renal artery stenosis is known to be present, or if any allergy to ACE inhibitors is present. Our AMI CPG Team recommends starting with 6.25 mg of captopril or 2.5 to 5 mg of lisinopril, with titration to maximum tolerated dose in approximately 48 hours.

Empiric intravenous magnesium in acute MI patients has not been shown to decrease mortality and is not routinely recommended. However, magnesium deficits should be aggressively replaced, especially if ventricular arrhythmias are present. Routine use of intravenous lidocaine is not recommended. Calcium channel blockers are now rarely recommended in the setting of AMI. Short acting nifedipine is contraindicated due to hypotension and the reflex activation of the sympathetic nervous system it causes. Diltiazern and verapamil are contraindicated in patients with LV dysfunction or CHF. Verapamil or diltiazem may be used in select circumstances, such as cases where beta blockers are contraindicated and rate control of atrial fibrillation is needed. Please see the ACC/AHA Guideline for a more detailed discussion of the management of the complications of acute MI, such as heart block, arrhythmias, heart failure, and shock. Immediate cardiology consultation is recommended for patients with any significant MI complications.

If the early ICU/CCU course is unremarkable, MI patients may be transferred to TCU 24 to 36 hours after admission. Patients who should be observed longer in the ICU/CCU include those with recurrent or persistent chest pain, congestive heart failure, hypotension, heart block, and/or significant arrhythmias. Higher risk patients need to stay longer in the ICU/CCU and should be considered for early referral for cardiac catheterization and revascularization. For the uncomplicated patient, 2 to 4 days in the telemetry unit are recommended to accomplish further education and early cardiac rehabilitation prior to discharge home. The last few days of hospitalization are important for the patient to be introduced to the cardiac rehabilitation team whenever possible, and be educated about what has happened and what to expect. Education should have already been started in the ICU/CCU and needs to be continued throughout the hospitalization. Thus, the total hospitalization for uncomplicated patients is usually 3 to 5 days.

*For the uncomplicated patient, 2 to 4 days in the telemetry unit are recommended to accomplish further education and early cardiac rehabilitation prior to discharge home.

*The greatest benefits seen for early ACE inhibitors are in patients with anterior MI, prior MI, CHF, tachycardia, or other evidence of low ejection fraction.

*Calcium channel blockers are rarely recommended in the setting of acute MI and short acting nifedipine is contraindicated.

Further risk stratification of these patients is recommended either prior to discharge or early after discharge as discussed in the next section.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND INDICATIONS FOR CARDIAC CATHETERIZATION

High risk patients with mechanical complications or hemodynamic instability should undergo urgent cardiac catherization.

Patients with acute MI and cardiogenic shock should be strongly considered for primary PTCA.

Echocardiography is a useful tool to assess LV function, and to identify mural thrombus.

In the initial 24 to 48 hours of treatment, the goal is to limit infarct size and prevent, identify and treat complications. Later in the hospital course, one of the goals is to identify patients at high risk of early death or reinfarction. It is well accepted in clinical practice with support from the literature that clinically high risk patients should undergo cardiac catheterization and, if indicated, revascularization in order to improve their short and long-term survival, as well as their quality of life. Thus, patients with post infarction angina, clinical congestive heart failure, or late ventricular tachycardia (after 24-48 hours from onset of infarction) should strongly be considered for invasive evaluation. Of course, the highest risk patients are those with persistent hemodynamic instability or mechanical complications of infarction (acute mitral regurgitation, septal or free wall rupture) and should be referred immediately for catheterization and surgery, usually with insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump.

Patients who have not been identified as high risk clinically, should undergo further testing during the latter part of the hospitalization or soon thereafter, including an estimate of left ventricular function. Echocardiography is a useful tool to assess LV function globally and segmentally, and to identify mural thrombus formation which would indicate the need for a longer period of anticoagulation. Echocardiography is needed immediately when mechanical problems are suspected (tamponade, papillary muscle rupture, septal rupture). Patients who cannot be imaged adequately with echocardiography can have their LV function gauged with radionuclide ventriculography (MUGA). Patients identified with reduced LV ejection fraction below 45% fall into the high risk category and should also be strongly considered for cardiac catheterization in addition to long-term treatment with ACE inhibitors.

Patients with small inferior or subendocardial infarctions, or those undergoing cardiac catheterization for other reasons, may not need to be evaluated by echo or nuclear ventriculography.

Stress testing has become a major non-invasive risk stratification tool to assess the post infarction patient. In general, patients able to undergo exercise stress testing post infarction tend to be in a lower risk group; however, their risk of mortality and/or reinfarction in the first year post MI is significantly higher if there are ischemic changes during exercise, or if they are unable to complete at least 5 METS (this is equivalent to 3 completed stages of the modified Bruce Protocol, I stage of the regular Bruce Protocol, or 3 stages of the Naughton Protocol). The risk of mortality and/or reinfarction also increases if there is significant ischemia demonstrated by supplemental imaging techniques (stress echo or thallium/sestamibi). These patients should generally be referred for invasive evaluation.

There are several acceptable options- in timing, type, and protocol- for post infarction stress testing. Low level predischarge exercise tests can be done 3 to 5 days post infarction and are best done on current therapy, including a beta blocker. These tests can identify patients with significant ischemia at low workload, but also give the physician a functional assessment of the patient's capabilities and may provide a psychological benefit to the patient. These tests are usually stopped when a patient reaches a heart rate of 120-130 beats per minute or 70% of predicted maximum heart rate, a peak work level of 5 METS, or if there is any angina, significant ST depression, hypotension, or 3-beat ventricular arrhythmias. Patients who do not demonstrate ischemia on a low level test can be safely discharged on medical therapy and then undergo symptom limited maximal stress testing 3 to 6 weeks post discharge. For maximum sensitivity at detecting ischemia, beta blockers (and other anti-anginal therapy) may be held (at the discretion of the physician) prior to these maximal tests. An acceptable alternative strategy is to perform only one stress test, a maximal symptom limited test, usually 2 to 3 weeks post infarction (but may be safely done as early as 5 days post infarction).

Maximal stress testing is strongly recommended for patients who will be returning to vigorous work. If LVH.LBBB, or significant ST-T abnormalities are present on the resting ECG, or if the patient is taking digoxin, supplemental imaging should be used to improve the sensitivity and specificity of the test.

In elderly, sedentary or other patients who are unable to adequately exercise, usual modes of stress testing are often inadequate to provide the answer to the clinical question desired. Pharmacologic stress testing may be an option for these patients, and include such tests as dobutamine stress echo, dipyridamole or adenosine stress thallium (bronchospastic disease is a contraindication to intravenous dipyridamole stress testing, and any caffeine-including the small amounts in "decaf" coffee-may nullify the physiologic effect of the agent). One should probably not proceed with these tests if the patient is not a candidate for or not willing to accept recommendations for invasive evaluation. Also, stress testing of any kind is contraindicated within 3 days of the acute MI or if there is unstable postinfarction angina, uncompensated congestive failure, or active significant arrhythmia.

Other noninvasive tests that have been studied in the post-infarction population include ambulatory Holier monitoring, signal averaged ECG, and heart rate variability monitoring. None of these are routinely recommended as there has been no demonstrable clinical utility associated with testing.

Risk stratification via cardiac catheterization is often done in patients post infarction who do not meet any of these clinical or non-invasive testing criteria. The literature support for other indications is either lacking or controversial. Practice patterns vary widely throughout the country and vary somewhat from Kaiser facility to facility and among various cardiologists at a given facility. Practice patterns range from recommending invasive evaluation only if the patient is identified as higher risk as discussed previously, to recommending catheterization for virtually every post infarction patient.

There have been several published studies on the use of catheterization and PTCA post thrombolytic therapy for MI. When PTCA is done routinely within 24 to 48 hours post thrombolytic therapy there has been higher morbidity and mortality, including higher rates of recurrent infarction. Also, routine catheterization later in the hospitalization has not been shown to be a more effective strategy than a more conservative approach with medical therapy and catheterization only for those identified as higher risk either clinically or by risk stratification tests. However, research in this area is evolving rapidly, and newer therapies such as stents and anti platelet IIb/IIIa agents are already yielding better results than we have seen in the past with PTCA alone.

There is also debate regarding use of catheterization post infarction in evaluation of the younger patient. In favor of preceding with catheterization is to better establish prognosis in someone with many productive years yet to live, and "we should just know what's going on in there." On the other hand, the younger patient usually has a better prognosis anyway, less chance of triple vessel disease, and can be risk stratified noninvasively. One must also remember that coronary angiography gives anatomic information only and cannot predict which plaque might become unstable in the future.

High risk patients that include those with LV dysfunction, post infarction angina, clinical CHF, or ischemia on stress testing should be considered for cardiac catherization.

Patients with relatively normal LV function and no symptoms with progressive activity during the hospitalization, may be risk stratified with stress testing.

Another area of controversy includes the "subendocardial" or "non-Q-wave infarction" patients. There is literature to suggest that these patients are at higher risk of reinfarction and therefore should be invasively evaluated for possible revascularization. The clinical estimate of the consulting cardiologist that there is a significant amount of myocardium still in jeopardy in these cases (or in other cases) is often cited as the indication of coronary angiography. There is also literature to support the strategy of identifying those higher risk patients in this group via standard noninvasive risk stratification tests.

A special situation is deciding whether to perform coronary angiography and PTCA immediately (within hours) after clinically failed thrombolytic therapy. There are clinical benefits of obtaining a patent infarct artery. These include improved mortality, improved LV ejection fraction with less remodeling, and less malignant arrhythmias. Unfortunately, there are many challenges with this approach.

First of all,it is often difficult to clinically diagnose "failed thrombolysis".

Also, the time delays result in diminishing returns in terms of salvaging myocardium.PTCA may fail in up to 10 % of these 'rescue PTCA" or "adjunct PTCA" situations, and reocclusion rates are higher. Furthermore, there is increased morbidity and mortality when the procedure fails. It is known that "if left alone" infarct artery

In elderly, sedentary or other patients who are unable to adequately exercise, usual modes of stress testing are often inadequate to provide the answer to the clinical question desired. Pharmacologic stress testing may be an option for these patients, and include such tests as dobutamine stress echo, dipyridamole or adenosine stress thallium (bronchospastic disease is a contraindication to intravenous dipyridamole stress testing, and any caffeine-including the small amounts in "decaf" coffee-may nullify the physiologic effect of the agent). One should probably not proceed with these tests if the patient is not a candidate for or not willing to accept recommendations for invasive evaluation. Also, stress testing of any kind is contraindicated within 3 days of the acute MI or if there is unstable postinfarction angina, uncompensated congestive failure, or active significant arrhythmia.

Other noninvasive tests that have been studied in the post-infarction population include ambulatory Holier monitoring, signal averaged ECG, and heart rate variability monitoring. None of these are routinely recommended as there has been no demonstrable clinical utility associated with testing.

Risk stratification via cardiac catheterization is often done in patients post infarction who do not meet any of these clinical or non-invasive testing criteria. The literature support for other indications is either lacking or controversial. Practice patterns vary widely throughout the country and vary somewhat from Kaiser facility to facility and among various cardiologists at a given facility. Practice patterns range from recommending invasive evaluation only if the patient is identified as higher risk as discussed previously, to recommending catheterization for virtually every post infarction patient.

There have been several published studies on the use of catheterization and PTCA post thrombolytic therapy for MI. When PTCA is done routinely within 24 to 48 hours post thrombolytic therapy there has been higher morbidity and mortality, including higher rates of recurrent infarction. Also, routine catheterization later in the hospitalization has not been shown to be a more effective strategy than a more conservative approach with medical therapy and catheterization only for those identified as higher risk either clinically or by risk stratification tests. However, research in this area is evolving rapidly, and newer therapies such as stents and anti platelet IIb/IIIa agents are already yielding better results than we have seen in the past with PTCA alone.

There is also debate regarding use of catheterization post infarction in evaluation of the younger patient. In favor of preceding with catheterization is to better establish prognosis in someone with many productive years yet to live, and "we should just know what's going on in there." On the other hand, the younger patient usually has a better prognosis anyway, less chance of triple vessel disease, and can be risk stratified noninvasively. One must also remember that coronary angiography gives anatomic information only and cannot predict which plaque might become unstable in the future.

High risk patients that include those with LV dysfunction, post infarction angina, clinical CHF, or ischemia on stress testing should be considered for cardiac catherization.

Patients with relatively normal LV function and no symptoms with progressive activity during the hospitalization, may be risk stratified with stress testing.

Another area of controversy includes the "subendocardial" or "non-Q-wave infarction" patients. There is literature to suggest that these patients are at higher risk of reinfarction and therefore should be invasively evaluated for possible revascularization. The clinical estimate of the consulting cardiologist that there is a significant amount of myocardium still in jeopardy in these cases (or in other cases) is often cited as the indication of coronary angiography. There is also literature to support the strategy of identifying those higher risk patients in this group via standard noninvasive risk stratification tests.

A special situation is deciding whether to perform coronary angiography and PTCA immediately (within hours) after clinically failed thrombolytic therapy. There are clinical benefits of obtaining a patent infarct artery. These include improved mortality, improved LV ejection fraction with less remodeling, and less malignant arrhythmias. Unfortunately, there are many challenges with this approach.

First of all,it is often difficult to clinically diagnose "failed thrombolysis".

Also, the time delays result in diminishing returns in terms of salvaging myocardium.PTCA may fail in up to 10 % of these 'rescue PTCA" or "adjunct PTCA" situations, and reocclusion rates are higher. Furthermore, there is increased morbidity and mortality when the procedure fails. It is known that "if left alone" infarct artery patency rises from 65 - 75 % at 90 minutes to 90% by 24 hours post thrombolytic therapy. This late reperfusion may improve survival without the risk of invasive procedures. Nonetheless, with stents and the anti platelet IIb/IIIa drugs, the overall benefit gained from this approach in very select patients makes it a reasonable treatment to consider (especially for larger infarcts where the time frame is such that myocardial salvage is expected). If such a strategy is used, transportation to a high volume center with an experienced operator, as discussed under primary PTCA, is recommended.

To summarize, patients with relatively normal LV function and no symptoms with progressive activity during the hospital course, may be risk stratified with a low level predischarge exercise test followed by a maximal test at 3 to 6 weeks post discharge, or alternatively undergo a single maximal stress test at 2 to 3 weeks post infarction. Patients with mechanical complications and/or hemodynamic instability should undergo urgent catheterization and intervention if possible. Other high risk patients that include those with LV dysfunction, post infarction angina, clinical CHF, late malignant arrhythmias or ischemia on stress testing should also be considered for cardiac catheterization. Other patients will have catheterization based on the preference of the individual patient and the clinical judgement and practice patterns of the attending physicians.

Long term anticoagulation is indicated in patients with atrial fibrillation or left ventricular thrombus and should be considered in those patients with significan LV dysfunction.

PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY

The term "primary angioplasty" refers to the strategy of treating acute myocardial infarction with emergency coronary angiography and reperfusion via device based mechanical techniques, collectively referred to as "angioplasty" These include balloon angioplasty with or without placement of an intracoronary stent device, atherectomy, and rotoblation. These techniques are often combined with pharmacologic therapies aimed at intracoronary thrombus dissolution.

Despite a decade of study, debate continues regarding the comparative merits of primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for AMI. Recent advances in device therapy and anti-platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa drugs make primary angioplasty an attractive alternative for certain patients treated in catheterization facilities with surgical back-up and an experienced staff. The cost savings in primary angioplasty are derived almost entirely from reduced length of ICU stay and total hospitalization. The reduced mortality is felt to be related to a higher infarct artery patency and brisk flow rate compared to thrombolytic therapy.

There are several problems with recommending primary angioplasty as the desired approach for the majority of patients. Most hospitals throughout the United States do not have catheterization facilities, and those that do may not be available for emergency procedures. Also, studies have demonstrated unequivocally that primary angioplasty is not preferable when performed in low volume centers or by less experienced interventional cardiologists, where the morbidity and mortality are higher than for patients treated with thrombolysis.

Although absolute guidelines for primary angioplasty are lacking, the recommendations are as follows:

1. Patients in cardiogenic shock with AMI have significantly improved survival with emergency coronary angioplasty (or coronary artery bypass surgery).

2. Primary angioplasty should be strongly considered for patients who qualify for reperfusion, but have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy.

3- Primary angioplasty should be performed only by high volume interventionalists (greater than 75 PTCA procedures per year) experienced with all devices and drugs that might be helpful, working at high volume centers (more than 200 PTCA procedures per year) with cardiac surgery availability. Furthermore, performance criteria include initial PTCA success rates of at least 85%, with 90% of these patients achieving a good result (good flow, no CABG, stroke, or death). Emergency CABG rates alone need to be less than 5%, and total mortality rates less than 12% (excluding cardiogenic shock patients).

4. "Time is muscle"-rapid thrombolysisis preferable to late mechanical reperfusion. Centers performing primary angioplasty are expected to achieve "door-to-balloon" time of less than 90 minutes.

5. The high risk patient (e.g., large anterior infarction) will benefit more from emergency management in the catheterization laboratory than the low risk patient.

6. Clinically failed thrombolysis with ongoing clinical instability (pain, ST elevation) is an indication for emergency (adjuvant or "rescue") coronary angiography and mechanical reperfusion.

Primary angioplasty should be strongly considered for patients who qualify for reperfusion but have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy.

"Time is muscle" - rapid thrombolysis is preferable to late mechanical reperfusion.

Thus, the choice of primary angioplasty as initial reperfusion strategy is an individual decision base( on judgment of the expected risk/benefit ratio for: specific patient. It requires knowledge of the skill and experience of the interventional cardiologist, and the full support of a high volume referral center to provide the service in a timely fashion. For facilities without cardiac catheterization and surgery it is important that referral and transfer protocols to appropriate centers be established in advance.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Secondary prevention of CHD (coronary heart disease) in patients after MI is critical to decrease the rate of recurrent cardiac events. It has been estimated that the incidence of myocardial infarction in post MI patients is 4-7 times higher than in patients with no prior infarctions. Secondary prevention includes smoking cessation, lipid lowering via diet and medication, weight reduction, exercise, stress reduction, and the appropriate use of aspirin, beta blockers and ACE inhibitors. Tight control of hypertension and diabetes in patients with these conditions is also important. Smoking cessation is essential. It should be introduced during the hospitalization, and this education should be documented. Follow up encouragement should be provided either with a Multifit RN, other cardiac rehabilitation program, or a local health education program, in addition to the patient's primary care physician.

Multiple studies have documented that low density lipoprotein (LDL) reduction to less than 100 mg/dl can prevent recurrent events. During hospitalization, patients should have a full cholesterol panel measured. These measurements are accurate if obtained <24 hours into an acute infarction, otherwise results may be falsely low until 4 weeks post infarction. Based on those results, or results of prior lipid panels, strong consideration should be given to starting appropriate lipid lowering medication such as 1020 mg/day of lovastatin with consideration of the addition of niacin after a six week post discharge fasting lipid panel. In the Post MI Clinical Pathway, fasting lipid panels are done at 6 weeks and at 4 months post infarction, and thereafter by algorithm (see Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cholesterol Management). Diet therapy with AHA Step II Diet (<7% total calories as saturated fat) is recommended. Drug therapy can be modified depending on the lipid panels (see protocol).

patency rises from 65 - 75 % at 90 minutes to 90% by 24 hours post thrombolytic therapy. This late reperfusion may improve survival without the risk of invasive procedures. Nonetheless, with stents and the anti platelet IIb/IIIa drugs, the overall benefit gained from this approach in very select patients makes it a reasonable treatment to consider (especially for larger infarcts where the time frame is such that myocardial salvage is expected). If such a strategy is used, transportation to a high volume center with an experienced operator, as discussed under primary PTCA, is recommended.To summarize, patients with relatively normal LV function and no symptoms with progressive activity during the hospital course, may be risk stratified with a low level predischarge exercise test followed by a maximal test at 3 to 6 weeks post discharge, or alternatively undergo a single maximal stress test at 2 to 3 weeks post infarction. Patients with mechanical complications and/or hemodynamic instability should undergo urgent catheterization and intervention if possible. Other high risk patients that include those with LV dysfunction, post infarction angina, clinical CHF, late malignant arrhythmias or ischemia on stress testing should also be considered for cardiac catheterization. Other patients will have catheterization based on the preference of the individual patient and the clinical judgement and practice patterns of the attending physicians.

Long term anticoagulation is indicated in patients with atrial fibrillation or left ventricular thrombus and should be considered in those patients with significan LV dysfunction.

PRIMARY ANGIOPLASTY

The term "primary angioplasty" refers to the strategy of treating acute myocardial infarction with emergency coronary angiography and reperfusion via device based mechanical techniques, collectively referred to as "angioplasty" These include balloon angioplasty with or without placement of an intracoronary stent device, atherectomy, and rotoblation. These techniques are often combined with pharmacologic therapies aimed at intracoronary thrombus dissolution.

Despite a decade of study, debate continues regarding the comparative merits of primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for AMI. Recent advances in device therapy and anti-platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa drugs make primary angioplasty an attractive alternative for certain patients treated in catheterization facilities with surgical back-up and an experienced staff. The cost savings in primary angioplasty are derived almost entirely from reduced length of ICU stay and total hospitalization. The reduced mortality is felt to be related to a higher infarct artery patency and brisk flow rate compared to thrombolytic therapy.

There are several problems with recommending primary angioplasty as the desired approach for the majority of patients. Most hospitals throughout the United States do not have catheterization facilities, and those that do may not be available for emergency procedures. Also, studies have demonstrated unequivocally that primary angioplasty is not preferable when performed in low volume centers or by less experienced interventional cardiologists, where the morbidity and mortality are higher than for patients treated with thrombolysis.

Although absolute guidelines for primary angioplasty are lacking, the recommendations are as follows:

1. Patients in cardiogenic shock with AMI have significantly improved survival with emergency coronary angioplasty (or coronary artery bypass surgery).

2. Primary angioplasty should be strongly considered for patients who qualify for reperfusion, but have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy.

3- Primary angioplasty should be performed only by high volume interventionalists (greater than 75 PTCA procedures per year) experienced with all devices and drugs that might be helpful, working at high volume centers (more than 200 PTCA procedures per year) with cardiac surgery availability. Furthermore, performance criteria include initial PTCA success rates of at least 85%, with 90% of these patients achieving a good result (good flow, no CABG, stroke, or death). Emergency CABG rates alone need to be less than 5%, and total mortality rates less than 12% (excluding cardiogenic shock patients).

4. "Time is muscle"-rapid thrombolysisis preferable to late mechanical reperfusion. Centers performing primary angioplasty are expected to achieve "door-to-balloon" time of less than 90 minutes.

5. The high risk patient (e.g., large anterior infarction) will benefit more from emergency management in the catheterization laboratory than the low risk patient.

6. Clinically failed thrombolysis with ongoing clinical instability (pain, ST elevation) is an indication for emergency (adjuvant or "rescue") coronary angiography and mechanical reperfusion.

Primary angioplasty should be strongly considered for patients who qualify for reperfusion but have contraindications to thrombolytic therapy.

"Time is muscle" - rapid thrombolysis is preferable to late mechanical reperfusion.

Thus, the choice of primary angioplasty as initial reperfusion strategy is an individual decision base( on judgment of the expected risk/benefit ratio for: specific patient. It requires knowledge of the skill and experience of the interventional cardiologist, and the full support of a high volume referral center to provide the service in a timely fashion. For facilities without cardiac catheterization and surgery it is important that referral and transfer protocols to appropriate centers be established in advance.

SECONDARY PREVENTION

Secondary prevention of CHD (coronary heart disease) in patients after MI is critical to decrease the rate of recurrent cardiac events. It has been estimated that the incidence of myocardial infarction in post MI patients is 4-7 times higher than in patients with no prior infarctions. Secondary prevention includes smoking cessation, lipid lowering via diet and medication, weight reduction, exercise, stress reduction, and the appropriate use of aspirin, beta blockers and ACE inhibitors. Tight control of hypertension and diabetes in patients with these conditions is also important. Smoking cessation is essential. It should be introduced during the hospitalization, and this education should be documented. Follow up encouragement should be provided either with a Multifit RN, other cardiac rehabilitation program, or a local health education program, in addition to the patient's primary care physician.

Multiple studies have documented that low density lipoprotein (LDL) reduction to less than 100 mg/dl can prevent recurrent events. During hospitalization, patients should have a full cholesterol panel measured. These measurements are accurate if obtained <24 hours into an acute infarction, otherwise results may be falsely low until 4 weeks post infarction. Based on those results, or results of prior lipid panels, strong consideration should be given to starting appropriate lipid lowering medication such as 1020 mg/day of lovastatin with consideration of the addition of niacin after a six week post discharge fasting lipid panel. In the Post MI Clinical Pathway, fasting lipid panels are done at 6 weeks and at 4 months post infarction, and thereafter by algorithm (see Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region Clinical Practice Guidelines for Cholesterol Management). Diet therapy with AHA Step II Diet (<7% total calories as saturated fat) is recommended. Drug therapy can be modified depending on the lipid panels (see protocol).

Exercise should begin gradually post infarction. Exercises that involve valsalva maneuvers such as moving furniture or weight lifting should be avoided in the first month, but brisk walking should be encouraged. Most patients who do not undergo catheterization during their hospitalization should be considered for stress testing. As discussed previously, this may include pro-discharge low level testing or symptom-limited stress testing 2-6 weeks post discharge. The maximal test is essential in determining a return to work date for patients with nonsedentary jobs. Patients without documented ischemia may safely resume sexual activity within one to three weeks. Driving with a companion may also begin within one to three weeks post discharge. Driving at high speeds, at night, or during rush hours should be avoided until after a satisfactory symptom-limited stress test. Commercial aircraft are only pressurized to 8000 feet. Air travel should be attempted only after patients are asymptomatic for two weeks or after a satisfactory low level stress test.

Uncomplicated MI patients with sedentary jobs may return to work as early as two weeks. Most patients with vigorous jobs will undergo symptom limited stress testing within one month post infarct and return to work at that time if results are satisfactory.

Smoking cessation is essential.

A maximal symptom-limited stress test is essential in determiining a return to work date for patients with nonsedentary jobs.

Multiple studies have documented that low density lipoprotein (LDL) reduction to less than 100 mg/dL can prevent recurrent events.

Aspirin is recommended after myocardial infarction in doses ranging from 81 mg - 325 mg daily and is to be continued indefinitely. All patients without a significant contraindication to beta blocker should be started on this medication in the hospital and continued indefinitely, with a goal of achieving a resting pulse < 65 bpm. Every patient should be discharged with sublingual NTG and instructions for its use. It is important that the physician emphasize to the patient that they not take sildenafil (Viagra‘) subsequent to their heart attack. Long term use of ACE inhibitors (unless contraindicated) is strongly encouraged in those patients with large infarcts, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) estimated less than 40%, diabetes, or uncontrolled blood pressure in spite of beta blockers. ACE inhibitors should be increased to the maximum dose tolerated. Patients who have intolerance to ACE inhibitors should be considered for an angiotensin receptor blocker or the combination of hydralazine/isosorbide. Long term anticoagulation is indicated in patients with atrial fibrillation or LV thrombus. It should be considered in those patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, significant systolic dysfunction, or patients unable to take aspirin. Also, women post MI should be educated about the risks and benefits of hormone replacement therapy in their individual situation. Although female AMI patients taking hormone replacement therapy should continue their medication after an MI, HRT is no longer recommended for secondary prevention of recurrent MI. Other antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel should be given if a patient is allergic to aspirin.

There is insufficient data yet to recommend vitamin E or vitamin C supplementation although foods rich in these vitamins should beencouraged. Homocysteine plays a role in a limited number of CHD cases. Although Vitamin B supplementation has been shown to reduce homocysteine levels, data as to whether it prevents vascular disease remains controversial. Selective screening for hyperhomocysteinemia should be considered in patients with premature CHD or those with a strong family history of CHD.

However, caution should be exercised in prescribing Vitamin B6 supplementation as amounts greater than 150 milligrams per day may be neurotoxic.

Promoting alcohol consumption in patients post MI as secondary prevention is controversial, particularly with regards to the optimal volume and frequency of drinking to obtain cardiovascular benefits, and to the encouragement of drinking in abstinent patients. Most national health organizations and researchers recommend that men consume no more than two drinks a day and women consume no more than one drink daily. A drink is defined as 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces of liquor.

In general, patients who don't drink should not be encouraged to begin "therapeutic drinking" because of the risk of developing alcohol-related problems.

Follow up after uncomplicated infarction should include an appointment at 7-10 days post discharge, 4-6 weeks, and three months. A cardiac rehabilitation program such as Multifit should be encouraged where available. Family members should be educated about secondary prevention efforts and trained in CPR technique.

Although female AMI patients taking hormone replacement therapy should continue their medication after an MI, HRT is no longer recommended for secondary prevention of recurrent MI.

Other antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel should be given if a patient is allergic to aspirin.

Family members should be educated about secondary prevention efforts and trained in COR technique.

TEN CLINICAL PEARLS

1. Primary prevention saves the most lives. This includes smoking cessation; diabetes, lipid, and weight control; aspirin in appropriate populations; the treatment of hypertension with beta blockers whenever possible; and perioperative use of beta blockers in high risk patients.

2. The effectiveness of newer therapies for acute myocardial infarction is strongly time-dependent. Educate patients with significant cardiac symptoms to present early.

3. All Emergency Departments should have a system for quickly evaluating potential AMI patients and delivering thrombolytic therapy in a timely fashion. The goal for door-to-drug time is less than 30 minutes.

4. Patients who qualify for reperfusion (thrombolytic therapy or primary percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) should receive it.

5. Aspirin is effective in the primary treatment of acute myocardial infarction and secondary prevention of recurrent myocardial infarction.

6. Beta blockers should be used whenever possible in AMI patients. This includes patients with diabetes, congestive heart failure, and/or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

7. ACE inhibitors are underutilized in the AMI population. Their use is encouraged, especially in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Look for reasons to use them, not avoid them.

8. Emergency coronary angiography and interventional treatment is strongly recommended for the treatment of AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock.

9- In cases where emergency angioplasty is indicated, the patient should be transferred to an interventional center. These referral patterns should be worked out in advance so as to allow prompt, smooth transfer of these critically ill patients.

10. Cardiologists should be involved in the care of most AMI patients.

Copies of the ACC/AHA guideline can be obtained by calling 1-800-253-4636 or by downloading from pubauth@amhrt.org

Pre-printed order forms are available to help with the implementation of guideline recommendations.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

General MI 1. Ryan TL Anderson JL, Antman EM, Braniff BA, Brooks NH, Califf RM, etal. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). 1996;28:1328-428.

2. Braunwald, E, editor. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997.

3. SelbyJV, Fireman BH, Lundstrom RJ, Swain BE, Truman AF, Wong CC, et al. Variation among hospitals in coronary-angiography practices and outcomes after myocardial infarction in a large health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1888-96.

4. Jesse RL, Kontos MC. Evaluation of chest pain in the emergency department. Curr Probl Cardiol 1997;149-236.

5. Recent developments in coronary intervention: GUSTO-III and other highlights from ACC '97. Clinical Challenges in Acute Myocardial Infarction 1997May;7(2):l-12.

6. Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, Kresowik TF, GoidJA, Krumholz HM, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative CardiovascularProject.JAMA 1998;279:1351-7.

7. Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, GurwitzJH, Guadagnoli E, Hauptman PJ, Borbas C, et al. Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279;1358-63.

8. SweeneyJP, Schwartz GG. Applying the results of large clinical trials in the management of acute myocardial infarction. WestJ Med 1996;164:238-48.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

General MI 1. Ryan TL Anderson JL, Antman EM, Braniff BA, Brooks NH, Califf RM, etal. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction). 1996;28:1328-428.

2. Braunwald, E, editor. Heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1997.

3. SelbyJV, Fireman BH, Lundstrom RJ, Swain BE, Truman AF, Wong CC, et al. Variation among hospitals in coronary-angiography practices and outcomes after myocardial infarction in a large health maintenance organization. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1888-96.

4. Jesse RL, Kontos MC. Evaluation of chest pain in the emergency department. Curr Probl Cardiol 1997;149-236.

5. Recent developments in coronary intervention: GUSTO-III and other highlights from ACC '97. Clinical Challenges in Acute Myocardial Infarction 1997May;7(2):l-12.

6. Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, Kresowik TF, GoidJA, Krumholz HM, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative CardiovascularProject.JAMA 1998;279:1351-7.

7. Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, GurwitzJH, Guadagnoli E, Hauptman PJ, Borbas C, et al. Effect of local medical opinion leaders on quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;279;1358-63.

8. SweeneyJP, Schwartz GG. Applying the results of large clinical trials in the management of acute myocardial infarction. WestJ Med 1996;164:238-48.

9. Coudrey L. The Troponins. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158:1173-91.

ACE Inhibitors

1. Nesto RW, Zarich S. Acute myocardial infarction in diabetes mellitus: lessons learned from ACE inhibition. Circulation 1998;97:12-5. [published erratum appears in Circulation 1998 Mar 3;97(8):81]

2. Barren HV, Michaels AD, Maynard C, Every NR. Use of angiotension converting enzyme inhibitors at discharge in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the United States: data from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. J Am Coil Cardiol 1998; 32(2):360-67.

Alcohol

1. Potter JD. Hoards and benefits of alcohol. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1763-4.

2. Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, Monaco JH, Henley SJ, Heath CW Jr, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1705-14.

Angioplasty

1. A clinical trial comparing primary coronary angioplasty with tissue plasminogen activator for acute myocardial infarction. The Global Use of Strategies to open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO IIb) Angioplasty Substudy Investigators. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1621-7. [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 1997 Jul 24;337(4):287]