MCRC - THE MANAGED CARE REFORM COUNCILMCRC is recognized by the State of California and the Internal Revenue Service of the United States of Americaas a Public Benefit - Not for Profit Corporation.Federal Identification Number: 42-1602037

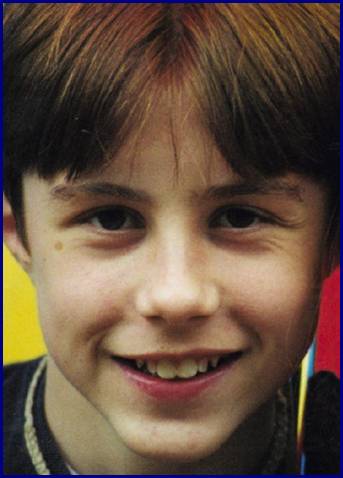

Lewis Blackman, a healthy, gifted 15-year-old, underwent elective surgery at MUSC. In one of the state's most modern hospitals, he bled to death over 30 hours while those caring for him missed signs that he was in grave peril.

LEWIS WARDLAW BLACKMAN

1985-2000

http://www.lewisblackman.net

LEWIS WARDLAW BLACKMAN

1985-2000

http://www.lewisblackman.net

The State Columbia, South Carolina

SPECIAL REPORT

Lewis Blackman, a healthy, gifted 15-year-old, underwent elective surgery at MUSC. In one of the state's most modern hospitals, he bled to death over 30 hours while those caring for him missed signs that he was in grave peril.

How a hospital failed a boy who didn't have to die

By JOHN MONK Staff Writer

Nothing indicated 15-year-old Lewis Wardlaw Blackman of Columbia had four days to live when he entered the Medical University of South Carolina Children's Hospital in Charleston.

Without knowing it, Lewis entered a little-known medical world where doctors, nurses and hospitals make mistakes that kill people.

That day, Thursday, Nov. 2, 2000, Lewis had the brightest of futures.

The weekend before, Lewis' parents - Helen Haskell, 49, and LaBarre "Bar" Blackman, 52 - had taken him and his sister, Eliza, 10, to North Carolina. There, Lewis saw Duke University, which his parents had attended.

Lewis was on track to sail into Duke, one of the nation's hardest schools to get into. He excelled in math, science, history and English. As a seventh-grader, he made the highest score in Richland County on a highly competitive Duke standardized test.

Ten days before he entered MUSC, he took the preliminary college board exam at his school, Hammond. After Lewis died, his parents learned he had scored the highest of any ninth-grader at the private school.

SPRITES AND GOBLINS

"Lewis was truly the most gifted student I've ever had - not that I haven't had others. In second grade, he wrote a story of a butterfly and drew this amazing picture of a butterfly, with all the parts. The book won first place in the school district visual literacy contest. He was such a good all-around kid, too. I know he would have done something great with his life. Whenever I see a butterfly, I think of Lewis."

- Nancy Jarema, teacher at A.C. Moore Elementary School for 27 years. She taught Lewis in the second and fifth grades.

Lewis had a "spark," says his mother, Helen Haskell.

At age 7, he was chosen - out of hundreds of children - to be in a Sun-Drop soda television commercial with NASCAR great Dale Earnhardt.

Ten months before he died, Lewis played the mischievous boy Mamillius in the S.C. Shakespeare Company's Finlay Park production of "The Winter's Tale."

In the play, Mamillius says: "A sad tale's best for winter: I have one of sprites and goblins."

A local reviewer wrote Lewis was "wonderful. . . . This young performer should go far."

In sixth grade at Hand Middle School, Lewis' teacher Caren Hazelwood told the students about a Columbia man who was trying to ban a book - "Mick Harte Was Here" - that the students loved. Lewis and his class wrote letters to the newspaper. The State published an excerpt from his letter.

"He who destroys a good book, kills reason itself," wrote Lewis, quoting 17th-century poet John Milton.

'LIKE GETTING BRACES'

"Lewis carried mirth around with him. He had this little light in his eyes, and he was very, very quick. As a teacher, I just wanted to work harder for him. When he died, my students and I were terribly upset. One girl didn't recover for months."

- Jeanette Arvay, Lewis' voice teacher, now at Dreher High School

Lewis was born with a condition called pectus excavatum. It means a crease in the chest cavity. About one in 500 people has it.

For years, medicine believed the defect was cosmetic. But recent studies have suggested it can cause respiratory problems if not corrected.

For years, Lewis' parents debated having an operation to correct the defect. But they decided it was too dangerous. The standard operation took as long as five hours. The whole chest was opened, and ribs and cartilage taken out. Then, a metal strut was put into the chest.

In 1999, Lewis' parents saw an article about a new operation at MUSC that supposedly was safer and quicker. In this operation, a metal bar is inserted through small incisions to prop up the breastbone.

The article, first published in The (Charleston) Post and Courier and reprinted in The State, was glowing. It described "a revolutionary type of surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina" for patients like Lewis.

The article quoted MUSC's Dr. Andre Hebra as saying he performed the surgery in an hour through two small incisions. His patient would be playing basketball and swimming "in a month or two," Hebra said.

Helen and LaBarre discussed the procedure with Lewis and with their Columbia doctor. They contacted MUSC doctors.

Everyone agreed it was a good idea - and safe. Helen said she and her husband were comforted by MUSC's reputation as the state's oldest and largest medical school.

"We thought it was like getting braces," Helen said.

THURSDAY, NOV. 2, THE FIRST DAY

"Lewis was really funny. He would even make jokes about his chest - that he could eat cereal out of it. He was also more mature. In seventh grade, when we were all telling fart jokes, he was making fun of political things. One of his favorite songs was 'Typical Situation' from the Dave Matthews Band. He said, no matter what mood he was in, that would make him feel better. I think about him a lot."

- Michael Hood, 15, one of Lewis' best friends, now a junior at Dreher High; the song "Typical Situation" is about protesting and accepting life's injustices

Lewis and his family arrive at the hospital at 6 a.m. The night before, the family - Helen, LaBarre, Lewis and sister Eliza - had driven to Charleston. Lewis chose where they ate, Poogan's Porch, a restaurant known for its Lowcountry dishes.

Lewis brings the book "Dune," the play "Julius Caesar" and a book on the Israeli spy agency, the Mossaad.

He also has his proudest possession: his new learner's permit to drive. Since his 15th birthday, Sept. 6, he's taken it everywhere.

The operation is set for 7:30 a.m.

Before the surgery, Helen recalls, the nurses ask Lewis for his weight, instead of actually weighing him.

That bothers Helen, who's not a nurse. An archaeologist by training, she nonetheless knows if drugs are to be administered, weight helps determine dosage.

"I insisted they weigh him," she recalls.

The surgery is supposed to last 45 minutes. It goes 2½ hours.

When lead surgeon Dr. Edward Tagge emerges, he says he had to reposition the metal bar in Lewis' chest four times to get it right. All in all, he says, Lewis did fine.

Lewis wakes in the recovery room. He tells doctors that his pain is about a "three" on a 1-10 scale.

At that time, nurses and doctors note in Lewis' record that he isn't producing urine.

This is crucial because, after the operation, Lewis is given Toradol, a powerful painkiller to soften his chest pain. Good urine flow helps dilute Toradol's side effects.

The Physicians Desk Reference gives clear warnings about the drug's side effects. Risks include perforated ulcers and internal bleeding. It says Toradol's use should be monitored. Roche, Toradol's maker, also notes the drug's "administration carries many risks."

Doctors routinely give medicines that carry risks. Usually, risks are monitored.

One of the failures in Lewis' case is that after the doctors prescribed Toradol - with its clearly stated deadly risks - no one notices Lewis is having a fatal set of reactions, according to his medical record.

Lewis is taken to Room 749 in the children's cancer ward. There's no room in the surgery ward.

FRIDAY AND SATURDAY, THE SECOND AND THIRD DAYS

"The things Lewis said! Like, he had a 10-minute Santa Claus joke. ‘.‘.‘. He could memorize things like anything. ‘.‘.‘. We had conversations that mesmerized me, talking about, 'What if the evil monkeys are still here?' after watching a television show that had evil monkeys coming from alternate dimensions. Six months after Lewis died, I fell asleep in class and woke up thinking he was alive. Then I went, 'Oh, no.'"

- Alex Crawford, 16, one of Lewis' best friends, now a junior at Dreher High

On Friday night, Dr. Tagge, who operated on Lewis, leaves for the weekend.

At 9 a.m. Saturday, surgeon Dr. Andre Hebra checks on Lewis.

"No evidence of infection. Clear lungs," Hebra writes in Lewis' medical record. "May sit up and consider getting out of bed."

Hebra is the last veteran doctor to see Lewis for two days.

Instead, Lewis' doctors will be apprentice doctors, called residents. A resident has a physician's license but, because of limited experience, must work under a veteran doctor's supervision.

Saturday night, Lewis begins to run a slight fever. His feet are cold to the touch. He is still on Toradol, taking it by intravenous line.

SUNDAY, THE FOURTH DAY

"On field trips, Lewis would be one of the kids to point out a spider. He would pick up on things other kids might miss or I might miss. He and his Writing Spider T-shirt helped inspire our school's writing excellence program. Every class had a spider's web with writings on it. Lewis was a great kid, very promising, and I often think, 'What if?' I'll never forget him."

- Darrell Weston, retired science teacher, Hand Middle School

At 6:30 a.m., a half-hour after another Toradol injection, Lewis gasps. He has horrible pain in his upper abdomen.

"It's the worst pain imaginable," Lewis says to his mother.

Helen summons the nurse, who wants to know how intense the pain is.

Lewis says his pain is "five on a scale of five."

He speaks in wonder, almost as if amazed that a human pain could be so bad, Helen recalls later.

That is the first indication the Toradol is eating a hole in Lewis' intestinal area. When this happens, blood and toxic material can leak into the abdominal cavity, a sterile place where some of the body's most vital organs are located. Toxic leakage and blood can kill.

Ordinarily, Lewis' pain would be an indication to call a full-fledged, veteran doctor, known as an "attending physician" or "attending," for short, said a medical expert who examined Lewis' case later.

Lewis is three days out of surgery and should be getting better. And this pain is in his stomach area - not in his chest, where he had the operation.

The nurse tells Lewis and Helen the pain is gas. "There's nothing I can do for gas pain," she says, Helen recalls later.

In nurses' notes that morning, a nurse writes, "gas pains ‘.‘.‘. pt. (patient) needs to move around."

Another nurse suggests a bath. She and Helen put Lewis in the tub and sponge him off.

"Afterward, he sits in the chair for a few minutes. This is a tremendous expenditure of energy for him. He seems to be getting weaker and weaker," Helen writes later in a diary that reconstructs Lewis' death.

Nurses insist Helen walk Lewis. Lewis says his pain is getting worse.

Over Lewis' feeble protests, mother and son lap the ward.

SUNDAY AFTERNOON

"We didn't insist Lewis have this surgery. It was his decision, but he did it because he knew we thought it was a good idea. He was scared to death to have surgery, and in that he was wiser than we were. When I think of the four of us tooling down the highway to our doom, the day after Halloween, I just weep. When I unpacked the car days later, after it was all over, I found it full of candy wrappers and drink boxes and CDs. Just like a family vacation. Just like always. Except Lewis never came home."

- Helen, Lewis' mother

Lewis' belly grows hard and distended, a sign of a possible intestinal perforation and internal leakage.

His temperature drops, his skin grows pale and he drips with a constant cold sweat. His eyes are sunken. He's exhausted, in great pain.

All are signs of what is called "acute abdomen" - a collection of potentially life-threatening symptoms. Experts say that veteran doctors know to act on seeing these symptoms. They assume the worst, acting quickly to check out a lethal condition - to rule it out, if nothing else.

Helen calls the nurse a number of times.

"She seems convinced that Lewis is simply lazy and not walking enough to dissipate his 'gas pain,'" Helen writes in her diary.

Outside the room, other nurses decorate the ward.

As Lewis grips her hand in pain, "I could hear the nurses chattering and laughing in the break room," Helen says later.

During Sunday, Helen repeatedly asks for a doctor. By that, she means a veteran doctor.

Instead, Helen gets a beginning resident. She will later learn the resident is four months out of osteopath college. Osteopaths are specialists in bones and muscles.

As Helen repeats her request, a nurse argues with her - offended Helen doesn't consider the resident a real doctor.

The resident too is upset at Helen's insistence on a veteran physician. "She also is offended, and appears extremely downcast that I have questioned her judgment. ‘.‘.‘. I reiterate Lewis' alarming symptoms once again: the pallor, the dark circles, the cold sweat, the unremitting abdominal pain," Helen writes later in her dairy.

"She stands at the computer and nods glumly, but never says a word. My impression is that she is too angry to speak.

"Somewhere along the line, my request for an attending physician has been quietly shelved. I do not know who made this decision."

At 6:26 p.m., Helen's insistence is such that a nurse writes in Lewis' record: "Parent requesting upper level M.D."

At 8 p.m. Sunday, the chief resident, Dr. Craig Murray, comes to Lewis' room. A chief resident has more seniority than other residents but still is under the supervision of a veteran doctor.

Helen believes Murray is the veteran doctor she has been waiting for. If Murray has identification on him to the contrary, she misses it.

Murray checks Lewis. He writes in the record: "probable ileus." That means: blocked intestine.

Murray orders a suppository to ease the supposed blockage.

Murray also writes that Lewis' heart rate is in the 80s, slightly above normal but no cause for alarm.

However, at the same time, a nurse notes in the record that Lewis' heart is beating 126 times a minute - another sign something may be horribly wrong. The nurse also records Murray has been made aware of Lewis' sweating.

Murray has a confident manner, Helen recalls. He says Lewis' sweating and lowered temperature - 97.7 degrees, almost a full degree below normal - are "side effects" of the medicine because Lewis is so young.

Later Sunday night, with Lewis' pain still enormous, Helen begins a vigil. She stops trying to get a doctor. After all, the confident Murray came by. She believed he was a veteran physician.

"Neither Lewis or I sleep at all Sunday night. I have given up on the weekend staff and am waiting for morning when the regular staff and doctors will arrive."

That night, Lewis' heart rate rockets. At midnight, it is 142 beats per minute and his temperature is 95 degrees. At 4 a.m., his heart rate is 140 and his temperature is 96.6.

MONDAY, THE FIFTH DAY

"Lewis knew about all kinds of things. If you introduced something to the class, he wanted to tell all he knew about it, but he wasn't obnoxious. He was hungry to share his knowledge. In later years, even when he was older, he would never forget to come by and give me a hug."

- Loraine Lambert, Lewis' first-grade teacher at A.C. Moore Elementary School

More residents keep dropping by.

Sometime Monday morning, Lewis' gut pain suddenly stops.

In cases like Lewis', veteran doctors know sudden loss of pain can mean impending death.

However, in reaction to Lewis' loss of pain, a nurse says, "Oh, good," Helen writes later.

When Helen asks a resident about Lewis' pale color - his lips are the same shade as his skin - she recalls the resident says cheerily, "Oh, that's just that low blood pressure. It pulls the blood away from the capillaries to protect the vital organs."

An aide takes Lewis' vital signs. She can't find any blood pressure.

>From 8:30 to about 10:15 a.m., Lewis' record reflects, others try and fail to detect a blood pressure.

Lewis is bleeding to death internally.

Instead of summoning a veteran doctor, residents and nurses believe the blood pressure devices are broken. They try various devices, according to Lewis' medical record.

Nurses' notes say, "Unable to obtain B.P. (blood pressure). ‘.‘.‘. B.P. attempts on arms and legs unsuccessful."

Helen recalls, "The focus is entirely on the equipment. For two hours, aides try blood pressure cuff after cuff with no result. They try to take his blood pressure about 12 times."

Nurses' notes record Lewis' vital signs. At 8:30 a.m., his temperature is 96.7 - almost two degrees below normal. At 10:45 a.m., his heart rate is 155 beats per minute - almost twice as fast as normal. Lewis' heart is pumping so fast because he has lost so much blood internally; his heart is trying its best to pump what little blood is left.

Still, no one calls a veteran doctor, according to Lewis' medical records.

About noon, two technicians arrive to take a sample of Lewis' blood for tests. They get just a small sample.

"Lewis is deathly pale," Helen wrote. "As they take his blood, his speech becomes slurred. He is trying to say something I can't understand. He says it again, very carefully and with great difficulty: 'Ish ... going ... black.' "

It's going black.

Helen calls for help. She thinks Lewis has had a seizure.

Still, veteran doctors don't come. Instead, chief resident Murray walks in.

"Dr. Murray calls loudly, 'Lewis! Lewis!' He stands there for two minutes, then asks the parents and Eliza to leave the room," Helen writes later.

At that point, 30 hours after Lewis has shown signs of a potentially fatal condition, hospital staff springs into action. Somebody issues a full alert - a code. Surgeons rush in.

"We stand in the hall in disbelief, watching this scene from a bad TV movie. ... A pastor appears. I turn away in horror. He says, 'Don't worry. I come to all the codes,'" Helen writes.

Inside the room, doctors - this time, veteran doctors - work on Lewis. They do cardiopulmonary resuscitation. They shock his heart with electrical machines. They hook up intravenous lines, according to Lewis' medical records.

They work for 60 minutes.

Doctors officially record Lewis' death at 1:23 p.m. Monday - 31 hours after Lewis first said he was having horrible stomach pains.

At 2 p.m., Dr. William Adamson, the lead doctor during the attempt to save Lewis, writes in the record, "It is unclear why the patient expired at this time. We will pursue an autopsy."

"Someone comes to get us," Helen writes in her diary later. "The doctors want to talk to us. I am fearful they will tell us Lewis is brain-damaged. When we go into the room, there are five surgeons in green scrubs. One introduces himself as Dr. Adamson. He is the doctor on call. We have never seen him before. Dr. Adamson says, 'We lost him.'

"This makes no sense to me. He is speaking as though Lewis has lost a battle with a long illness. He has to repeat it several times before I understand. They say they have no idea what happened. "

Lewis' death is a mystery, Adamson tells Helen and LaBarre. Chief resident Murray found nothing wrong the night before, Adamson says.

Helen now realizes that, despite her repeated requests Sunday for a veteran doctor, the hospital sent a resident, Murray.

Adamson asks Helen for permission to do an autopsy.

She says, "No." Without knowing how, she feels the hospital killed Lewis. The only thing she can think, she later recalls, is: They aren't going to hurt my son any more.

Within hours, Helen gets advice from relatives and friends with medical backgrounds: Get an autopsy. She requests one.

The autopsy says Lewis bled to death internally because of a perforated ulcer. It shows his abdomen was filled with almost three liters of blood and digestive fluid.

A child Lewis' size has 4 to 5 liters of blood. This means Lewis lost most of his blood supply into his abdomen.

After the autopsy, Dr. Tagge calls Helen to tell her of Lewis' perforated ulcer and internal bleeding, Helen says.

A month later, when Helen meets Tagge to discuss the autopsy, she tells him how she had tried Sunday to summon a veteran doctor. He apologizes. He says the residents should have called him, she says.

Later, medical experts tell Helen that an experienced doctor, seeing Lewis Sunday, would have known to order routine blood tests that would have uncovered the problem.

Lewis should be alive, the experts tell Helen.

'IT'S HARD TO KILL A HEALTHY 15-YEAR-OLD'

"Lewis was always laughing. From the time he was a tiny baby, we have picture after picture of him exploding into peals of laughter. ‘.‘.‘. I think the thing that so many people found shocking was that this could happen to someone who was so full of life. He just brimmed with energy. What they don't know - but I do - is how casual it all was. It was the easiest thing in the world. They just filled him with toxic chemicals and let him die."

- Helen, Lewis' mother

MUSC sent Helen and LaBarre literature on how to go through the grieving process.

Helen knew that suing MUSC wouldn't bring Lewis back. But she felt she had to do something. She looked for a lawyer.

She found Richard Gergel, a Columbia lawyer who specializes in medical negligence cases.

To Gergel, Lewis' case was a clear case of "wrongful death." That's the legal term for the death of a person caused by the negligence of another.

Gergel had medical experts study Lewis' records. Those records include more than 100 pages of doctors', residents' and nurses' notes, made on an almost hourly basis, as well as charts and the autopsy. Gergel said the experts concluded that the medical residents and nurses should have summoned a veteran doctor or - at the least - honored Helen's repeated requests to call a veteran doctor.

"This is about a boy who bled to death over 30 hours in a hospital with modern technology and vast technical resources," said Gergel. "Our experts' main point was that Lewis wasn't properly monitored."

With Lewis' symptoms, a veteran doctor would have known to order a routine blood test - called a CBC - that probably would have shown Lewis was bleeding internally, Gergel said.

"The test costs about $30," said Gergel. "Our experts couldn't understand why it wasn't ordered. It's one of the most common tests in hospitals."

Gergel contacted the hospital's insurer. Negotiations began.

Helen also sent Lewis' medical record to an old friend, Dr. Gregg Korbon, a veteran anesthesiologist and former assistant professor at both the Duke and University of Virginia medical schools. Korbon has participated in thousands of operations, taught hundreds of medical students.

Korbon said he was appalled by what he saw. "Even a Boy Scout could have done better."

Lewis probably could have been saved up through Monday morning, Korbon said. "It's hard to kill a healthy 15-year-old."

Eleven months after Lewis died, and without a lawsuit being filed, MUSC's insurer paid Lewis' estate $950,000. That's almost the $1.2 million maximum a state-operated hospital can pay under S.C. law that limits payouts.

Lewis' parents say the money will go for scholarships and to work for better patient safety. They are setting up a foundation.

"It's public money," said Helen. "This is money we want to give back to the state of South Carolina. It's Lewis' legacy."

In settlement documents, Helen laid out her claim:

"Petitioner ‘.‘.‘. asserts that MUSC was negligent in failing to properly prescribe and monitor the use of Toradol, monitor, assess and treat postoperative complications, provide adequate, experienced attending physicians to monitor assess and treat Lewis, and conduct a timely and appropriate resuscitation effort."

'OUR SYSTEM BROKE DOWN'

"Lewis was just one of those boys who would have made a real difference in the world. He had this particular combination of intelligence and enthusiasm and essential goodness. People loved him."

- Mary Jeffcoat, Lewis' longtime drama teacher

Since Lewis' death, Helen has been to MUSC three times at her request to speak with doctors and administrators. She wanted to speak to them about the dangers of Toradol and her perception that MUSC put too much responsibility on inexperienced residents.

Helen also wanted to speak to the medical residents about how Lewis died.

The hospital denied that request. However, MUSC said it has instituted patient safety reforms since Lewis' death.

Nurses and residents now must call a full-fledged doctor if a family or patient requests it. Patients also will be given manuals explaining their rights. The manual will have a phone number of the lead doctor on their case.

Joe Good, MUSC's general counsel, said he personally was shaken by Lewis' case.

"Our system broke down," said Good. "It shook this place to the core. And, God knows, I hope we never see that again. ‘.‘.‘. This is the most tragic case I can recall in my 16 years here. ‘.‘.‘. We've got to do better."

Dr. Murray did not return phone calls.

Dr. Tagge keeps a picture of Lewis on his desk at MUSC.

"I can look directly at him every day," he said. "I don't want his death to have happened in vain."

In hundreds of operations that he's performed over his 11 years at MUSC, Lewis is the only child to have died unexpectedly, Tagge said.

Children's Hospital doctors and nurses were - and are - devastated by Lewis' death, he said. "It really sucks the life out of you."

Lewis' death has brought changes, he said.

The children's surgery unit has trimmed its use of Toradol. It also now utilizes a pre-surgical procedure that cuts down on intestinal blockages after operations. Those blockages were common, Tagge said. That's one reason residents didn't take more action; they believed Lewis had a blockage, Tagge said.

Although parents and patients always had the right to call a veteran doctor, that standard has been reinforced, Tagge said.

Tagge said he accepts responsibility for what happened.

"As a surgeon, if something happens to your patient, you always accept responsibility. I'm the captain of the ship, and if something goes wrong, it's my responsibility. ‘.‘.‘. It's all under our watch. Absolutely, we take responsibility. That's why we feel so deeply, and that is why we have changed."

Still, he said, Lewis' case was not as simple as it might have looked. "This was a one in a zillion case," he said.

Blood from a bleeding ulcer of Lewis' type normally passes into the gastro-intestinal tract, where it is vomited up or passed out the colon - giving a clear sign that something bad is happening.

"He broke that rule," Tagge said. "His blood went into his peritoneal cavity and just sat there, which I've never seen before."

Perhaps, said Tagge, a veteran doctor seeing Lewis Sunday would have detected his serious condition.

But many doctors - possibly including himself - would have missed it, he said. "I can't say what I would have done if I were on the firing line."

Lewis' complication was "so unusual" it's understandable why it would be missed, Tagge said. "I don't know if I can say much more than that."

'I WONDER WHY'

After Lewis died, Helen and LaBarre got his belongings from the hospital.

Lewis' proudest possession - his new learner's permit to drive - was missing.

It was never found.

"I wonder why people have to die."

- Lewis, from a poem he wrote in the sixth grade

II

The Blackman family, October 1996 L to R: Helen, Eliza (age 6), LaBarre, Lewis (age 11)

© 2002 The State and wire service sources. All Rights Reserved. http://www.thestate.com DonateThe Baby Stories - The Youngest harmed by Managed Care